Understanding the workings of the consumer price index

For China's policymakers and the general population, the consumer price index is one of the most-watched indicators. But how the China CPI actually works is not readily transparent.

The CPI for March was released on April 9, showing a rise to 3.6 percent, down from 4.9 percent in January 2011.

Food inflation dropped to 7.5 percent from 10.5 percent in January 2012. Although these two indicators show that this round of inflation may have come to an end, concerns remain regarding the direction of the CPI and its volatility.

The CPI's high volatility can severely affect consumers' standards of living as the mismatch between income growth and expenditure growth continually causes consumers to rethink their spending decisions.

In China, the media and the general public ironically refer to the CPI as the "China pork index." On the surface, official figures make it clear that the meat CPI is behind much of the volatility in the overall CPI.

While the CPI is an official figure, the calculations behind the index are not publicly available. In July 2011, the CPI reached 6.5 percent, an alarming level that drove the government to take actions including putting price caps on some edible oils and releasing stocks from its pork reserve.

In China, food purchases account for 35 percent of urban household expenditure and 41 percent of rural household expenditure. Over the past decade, food expenditure for urban households has accounted for an overwhelming 62 percent of the CPI on average.

Clearly, the food CPI is a major driver of changes in the overall CPI. The CPI measures the weighted average of price changes of a basket of consumer goods and services. The two main components are the weighting of items composing the basket and their price fluctuation.

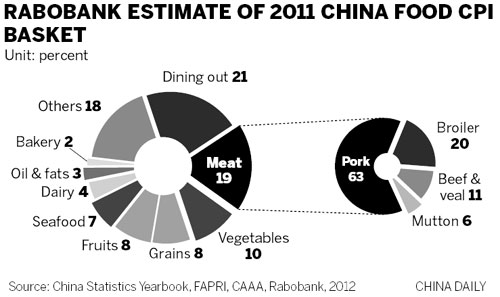

The food CPI basket remains mysterious as no official data on the breakdown has been released. While some have tried to estimate the basket by using complex regression models or by extracting information from official documents, Rabobank has fundamentally approached the mystery by using official data on food expenditure per capita.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the food CPI is composed of 16 major categories and includes 262 products. Although the weightings of food products in the food CPI are not disclosed to the public, the food expenditures within these categories are published on an annual basis.

By extrapolation, Rabobank assumes the weighting of items in the food CPI basket are equal to their weighting for food expenditures on an annual basis. Given the relatively high per capita meat consumption in China, the food CPI basket is a "meaty pie", which explains why the pork price matters.

Based on the CPI definition, price movement is reflected only if prices fluctuate. Rabobank tracked the monthly price volatility from the past decade of the major components of the food CPI. The most volatile item was the pork price.

Based on the official food item price movements and Robobank's food CPI basket estimation, the bank modeled the contribution of each major item in the food CPI. The model includes price movements of the major food items with a weight allocation system to track the contribution of the major food items.

Comprising a large proportion of consumers' food expenditures, meat plays a large role in determining the overall direction of the CPI. Pork was a major contributor to CPI hikes in July 2004, February 2008 and July last year.

Declining prices outweighed the uplift in CPI from other major food categories between February 2009 and July 2009.

Fruit and vegetables together have the third-largest weighting in the basket and their price volatility ranks second after pork.

Consequently, this category is the second-largest contributor to movements in the food CPI. Examples of periods in which fruit and vegetable price volatility had a large impact on the food CPI include August 2005 to September 2006 and February 2009 to April 2010, times when pork price movements were negative.

Pork's contribution to the food CPI is obvious given the correlated trend movements. Being one out of thousands of products within the CPI basket, pork is estimated to have a relatively high weighting of 3.6 percent in the China CPI.

Moreover, it is not uncommon to observe pork price movements of more than 40 percent compared with the previous year. Along with its severe price volatility, its impact is astonishing.

More people have started to see the connections between changes in pork prices and the CPI. Hence, reporters argue that pork has "kidnapped" the CPI due to its large weighting compared with other products and its high price volatility.

Rabobank admits that it is fair to state that the CPI in China could confusingly stand for the "China pork price" as the pork price accounted for an overwhelming share of CPI inflation over the past decade.

However, that could be an over-generalization. Even though the pork price generally has the largest contribution to the CPI, it does not explain the entire picture.

Given the model that Rabobank proposes, the leading driver of the CPI is a product with extreme volatility despite its weighting. Although pork price volatility has a major bearing on China's CPI volatility, it is reasonable that any product could take the lead whenever its volatility outweighs the other products in the basket.

One good example would be in 2006 and 2009, when fruit and vegetable prices took over from pork prices as the key driver of the CPI. Fruit and vegetable prices were able to lift the CPI even though meat prices were moving lower.

Hog inventories reached a record high of 469.2 million head in October 2009, causing oversupply in the market. The corn-to-hog price ratio fell below 6.0, which indicated many pig farmers were earning less or even losing money.

Instead of waiting for the next pork price cycle, many farmers exited the market and slaughtered massive numbers of hogs and sows.

The total hog and sow inventory fell 7.2 percent from to 481 million head between December 2010 and May 2011, which laid the foundation for another pork price inflation cycle in 2011. In addition, pork supply was further limited due to the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, which caused pork prices to rise 49 percent, contributing to 1.8 percent of the CPI increase.

Why are pork and fruit and vegetable prices so volatile?

First, it is fair to acknowledge that historically China has been reasonably successful in reducing commodity price volatility. While global grain commodity markets encountered a boom and bust in 2008-09, China's wheat and corn prices remained relatively stable.

Although food price volatility is driven by a diversified basket of food items, meat and fruit and vegetables have largely contributed to the food CPI.

China's pork price volatility is mainly caused by the mismatch between supply and demand. Pork demand has low price elasticity due to Chinese traditional consumption habits.

The Chinese prefer pork to other meats, and pork accounts for more than 63 percent of their meat expenditures. In general, there is low elasticity for consumers to shift meat consumption to other proteins such as poultry, beef or sheep.

Despite chronic soaring prices, pork remains the staple meat for Chinese consumers. Only under extreme conditions have we seen consumers ration demand for pork and/or substitute with poultry.

Therefore, pork price volatility is more driven by supply fluctuation rather than changes from the demand side.

China's pork sector still faces many challenges, despite its remarkable transformation along the value chain.

Although so-called backyard farmers represented 20 percent of China's pork production in 2011, down sharply from 34 percent in 2010, the production base is still highly fragmented.

The sector is at the mercy of high supply inconsistency, mainly due to diseases and low replenishment. Such unpredictable and disrupted supply means amplified price volatility.

In a similar way, fruit and vegetables suffer the same supply constraints. China's pork and vegetable supplies both account for about half of the world's production, although the industries are among the most fragmented in the world.

The lack of economies of scale in both sectors exposes small farmers to significant downside risks. Given the roller-coaster profit levels, many farmers go into the business in the hope of selling their production during periods of rising prices and do not invest or even exit the business when the market outlook is pessimistic.

But those who stay in pig farming all the time can still adjust the replenishment of piglets according to their price outlook. Such behavior has left the supply outlook quite unpredictable, resulting in volatile prices.

Additionally, the pork and fruit and vegetable supply chains still have numerous intermediaries who tend to speculate on price, amplifying price volatility.

Also, pork and vegetables are not homogeneous: Both have product differentiations (such as frozen pork versus fresh pork or carrots versus broccoli).

As pork and vegetable items are highly perishable, moving supply from one place to another in response to shortages is still an issue due to cold supply chain limitations and cost issues. Thus, a series of mismatches between supply and demand translate into volatility in price.

Therefore, we can assume that China's problem of curbing food CPI volatility could be partly solved by an improved mechanism for managing pork price volatility.

Looking ahead, Rabobank believes pork will remain the key contributor to volatility in the CPI. Being able to predict pork price fluctuations could give clarity to the CPI outlook.

Contact the writers at jeanyves.chow@rabobank.com, ivan.choi@rabobank.com, and chenjun.pan@rabobank.com