A mystery written in stone

Did Chinese explorers roam North America thousands of years before Columbus got there? A self-taught investigator says he has proof, and some top experts agree with him, Chris Davis reports from New York.

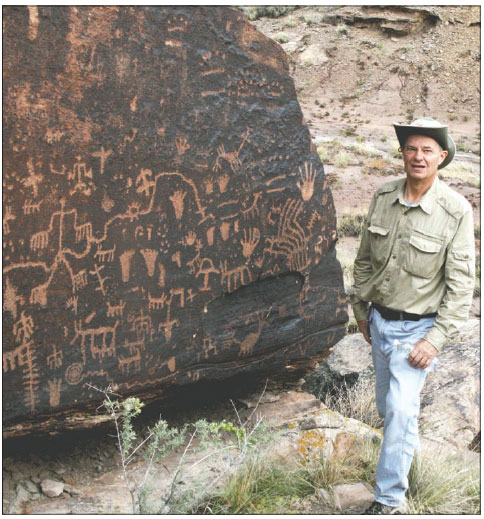

I n 2005, John Ruskamp, a retired statistician, was hiking with his family Nine-Mile Canyon in northeast Utah. All along the stretch of gravel road were rocks that had had "graffiti" carved, chiseled, scraped or pocked into them since no one knew when. Most of the figures were Native American designs, prehistoric petroglyphs, or rock art, pictorial and similar in style. Others were more recognizable names and words from more recent etchers.

Suddenly, on a steep incline, Ruskamp noticed a "glyph" that seemed out of place with the rest. It roughly resembled a drawing of a step ladder. "Wait a minute," he said. "I've seen that before. I know what that is."

During the Vietnam War, Ruskamp had been on two Western Pacific tours as a radioman aboard the aircraft carrier Constellation, which made stops in Hong Kong and Singapore, where he had gotten some exposure to Chinese culture, music and calligraphy.

"That's the Chinese symbol for a boat," he told his wife and family. He wasn't saying it was made by a Chinese passerby, but he felt sure whoever made it, picked it up from Chinese somehow. China was its origin. But how old was it? And were there more?

Then and there, having the luxury of a retiree's unspoken-for free time, Ruskamp and his wife Linda set themselves the challenge: Could they find other Chinese petroglyphs in North America?

From that remote corner of Utah, the Ruskamps started wandering trails, looking and looking. And sure enough they found another one, slightly different but, in their view, unquestionably Chinese. And then another. They've kept at it for the last 10 years, applying the most stringent statistical analysis Ruskamp could bring to bear. And their findings are now challenging the foundations of American archaeology and suggesting that China's own history books may need some emending.

History either way

"We've either proven that the Chinese were over here about 3,000 years ago; or Native Americans were the first people in all of human history to re-invent ancient Chinese writing," he added. "Either way, we've got a historic thing here."

"We've found, across the whole country - just where we've gone, of course, you can't go everywhere - 84, out of millions," Ruskamp said.

One of their most fantastic finds, he said, is right in the city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, at Petroglyph National Monument, a 17-mile-long volcanic basalt escarpment with more than 24,000 petroglyphs that have been engraved into its face starting - it was believed - about 700 years ago with the Zunis and Hopis and more recently by Conquistadors.

There are six or seven symbols depicting a man presenting himself to his superior making a ritual sacrifice of a dog. "Possibly to the Shang Dynasty Emperor Tai Jia (1535 to 1523 BC)," Ruskamp said. "It's actually readable. They cannot be faked. They're very complicated symbols which are uniquely Chinese."

Ruskamp enlisted the help of Michael F. Medrano, PhD, chief of the division of resource management at the monument. Medrano, who had been at the park 25 years, went out with them, looked at the glyphs and agreed that they did not seem Native American, and were certainly not Spanish.

The monument's unfunded mandate is to understand the glyphs and try to figure out what they mean. Medrano regularly met with tribal leaders, going over various glyphs, some claiming these, some claiming those. No one claimed what the Ruskamps had found.

"These images do not readily appear to be associated with local tribal entities," Medrano wrote to Ruskamp.

"It's pretty easily explained," Ruskamp said. "They're Chinese writing. Of course they're not claimed by Native Americans."

Furthermore, based on the amount of repatination, or patina from weathering, they "appear to have antiquity to them."

"Medrona said these are of age, these are not new, this isn't graffiti, this didn't happen in the last 100 years. So there's one real hot spot, Albequerque, New Mexico," Ruskamp said.

They found "another real good one" in the Petrified Forrest of Arizona right off of I-40 near Meteor Crater.

"There's a beautiful written symbol of an elephant," he said. "It's not a picture of an elephant, it's the word elephant, their symbol - xiang - for elephant right there in the monument."

Over the years they have found Chinese calligraphic figures gouged into rocks from Little Lake, California in the Mojave Desert, south of Las Vegas, and pretty much along I-40 all the way out to the panhandle of Oklahoma. They found one north of Toronto and a couple up in Minnesota. But most are in the Southwest. All, without doubt, readable Chinese.

And indeed they were, as confirmed by no less of an authority that David N. Keightley of UC-Berkeley, who won a MacArthur Genius Grant for his studies of the Oracle Bones - the oldest known form of Chinese writing.

"The incising mattered more than the writing," Keightley wrote, as they were "inscribed to leave a record rather than a document; the importance of the inscriptions was that they were there, that they existed, not that they were read."

"One of the top guys in the world and he's looked at these for me and said, 'Yes, John, those are Chinese symbols and, by the way, did you notice this one?' and [Keightley] pointed out one I hadn't noticed," Ruskamp said.

A profound find

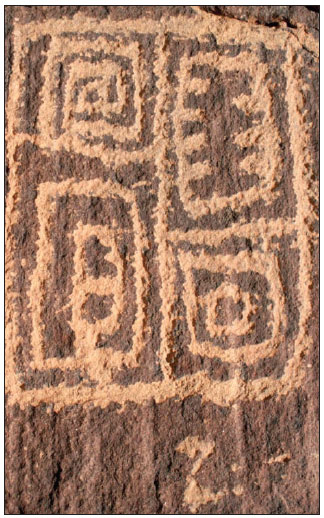

About 250 miles southwest of Albuquerque Ruskamp made what he called a "profound" find: a group of three numbered cartouches, or "frames", each holding four Chinese symbols. The group can be read as a poem in the stylized format of poetry around the time of Confucius, 500 BC. In rhyming patterns, they read: "Set apart 10 years together/declaring to return, the journey completed, to the house of the sun, the journey completed together."

Ruskamp put his years of statistical analysis to work. He used a simple scientific tool called Jaccard's Index of Similarity. A direct yes-or-no comparison of objects' parts often used in biology for verifying species, trying to figure out if this bug belongs to this group or that group - it's got eight legs, two antenna, four wings, etc, right down to minute detail.

Ruskamp adapted Jaccard's approach to the line strokes of written Chinese symbols, using information he gleaned from modern Chinese handwriting analysis to determine where the component lines of each symbol connect, intersect or form junctions. He compared the ancient petroglyphs' lines with the lines of known ancient Chinese symbols, like xiang for elephant.

Line by line, he entered the connection and relation of each line to each of the others, they either matched or they didn't match, onto the yes-or-no binary database. In the end, he tallied up the pluses versus minuses and got a Jaccard's value.

To be included in his study, the score had to be 95 percent or better. "I used that as the overriding philosophical determinant here," Ruskamp said. "With a 95 percent similarity level then that would hold up pretty much in a court of law.

"All 84 that we have - and some are absolute perfect matches - they're not simple letters like I or J or K, there are many line strokes in them that match perfectly."

Then he approached the experts: Ma Baochun of Capital Normal University in Beijing, who verified they were ancient Chinese characters, probably pre-Qin Dynasty, before 200 BC. Nanjing University's Fan Yuzhou looked at some of them and said, boy, this is pretty good, Ruskamp said. And, of course, David Keightley at Berkeley, who has become one of Ruskamp's strongest supporters.

All that remained was to figure out how old they were, not an easy task with prehistoric scratches on primordial stone. From the repatination levels on these glyphs in the desert or even up in Toronto, Ruskamp said you can tell roughly, not exactly, whether it was "new graffiti" from the last hundred years or whether these things had a lot of weathering on them and were quite old.

But there was an even more intriguing way to assign an age to some of the petroglyphs.

"In the absence of sufficiently prcised absolute dates, arrived at by carbon-14 dating or some other method," Keightley noted, "the inscriptions themselves provide our most reliable evidence for relative dating."

Nearly half - 40 - of the 84 were oracle-bone script, the earliest known form of Chinese writing dating back to the Shang Dynasty of 1,500 BC.

Ruskamp explains: "After the Shang Dynasty was overthrown by the Zhou in 1046 BC, each of the succeeding changes of emperors and dynasty would outlaw the Chinese writing that was used prior to them. Each regime would come in and say, 'Okay, we're not going to use the Shang scripts anymore. Those are illegal. We're now going to use our form of writing.'"

Forgotten script

Since the Shang oracle-bone style was outlawed, Chinese writing evolved through five or six iterations down to modern time. So, by implication, the style of writing on an object places it in the time frame of when that script was in use, since subsequent generations never learned it.

Oracle bone script was not known much after 1,000 BC, Ruskamp said. It was illegal to use it and very quickly fell into obscurity. It was not rediscovered until 1899, when a Chinese scholar named Wang Yirong recognized characters etched in bones and shells as an early form of Chinese writing.

"So between roughly 1,046 BC and 1899 AD, oracle bone symbols were unknown to mankind," Ruskamp said. "We found some in readable patterns."

That, Ruskamp said, means only one of two things: Either somebody reinvented Chinese writing, which has never happened in all humanity, or these are original scripts dating to the earliest times of Chinese calligraphy.

They are too old to have been done since 1899 and they're definitely not modern chance reproductions, he said. "You're looking at a thing 3,500 years old and the weathering shows," he said.

Ruskamp believes this has gone beyond the speculative. "It is ancient Chinese writing, readable, confirmed by expert authorities and located in the Americas," he said.

Ruskamp points to the fact that Native American Zuni and Hopi compasses use of the same colors for the cardinal directions of the compass - turquoise or blue (West), red (South), white (East), yellow (North) - that are found in China.

The Hopi have folklore of the Water Clan people who come on the backs of seven turtles from across the Great Western Sea, in other words, island hopping across the Pacific.

In 1800, Prussian explorer Alexander von Humbolt found in South America natives who used bamboo to protect the lines of their suspension bridges, exactly the way it was done during the Qing Dynasty near Tibet.

DNA analysis more recently confirms that all American Indians (except for maybe the Chippewa and a few other tribes in Michigan) right down to the South Americas have Asiatic genes. "So we know they came from Asia, the question is when?"

Ruskamp said that for more than 250 years, the US archaeology establishment has denied and rejected any suggestion that Asians explored North America. He said they claim there are not enough artifacts, not enough evidence.

Ruskamp believes his findings, though not artifacts, are still evidence. "It's not archaeology at all. It's epigraphy. It's ancient writing, not archaeology. I'm looking at ancient Chinese writings and scripts. I'm not looking for things in the ground. I'm not doing archaeology."

One of the critiques of Ruskamp's study, Asian Echoes, which is available on Amazon, brought up the lack of artifacts issue.

"If you have writing on the wall, what is that? It is the artifact. You don't need pottery or a sword or a belt buckle if you've got the writing on the wall and it's ancient and in an ancient form of script, you've got the artifact," he said.

It flies in the face of archaeology's golden rule: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

"What we've got here looks like an expedition," Ruskamp said. "This was a group of explorers which are found in ancient Chinese writings. China has the most ancient human written history of any on Earth. In 2,000 BC they talk about sending out expeditions to the Great Luminous Canyon of the Far East, way beyond Japan - that would be the Grand Canyon - to reset the calendar after the great flood.

"Then from 500 AD, there is a Chinese legal document, a deposition of a group of Buddhist monks who returned from a journey to what appears to be America and they recount the miles and it all fits with the West Coast and the Yuba Pass. And that is in the legal records of ancient China and you didn't lie to the emperor back then, you'd be cut apart," he said.

Ruskamp said his verified evidence represent s four different eras of Chinese writing. Most are very ancient. A few are more recent, from year 1 to 400-500 AD, and from there Chinese writing doesn't change that much, it's almost the same as today.

Regular visits

"What it shows is that [Chinese]people were coming over periodically. This wasn't a one-time event. They were coming over here more than one time. They introduced the symbols and I believe the Native American Indians took them for their own writing also. They saw the Chinese writing and said I can use that symbol myself and used them in their own Native American writing. So some of these symbols we found I believe were made by Indians who copied it and appropriated it from the Chinese. A natural human thing. I like that symbol I'll use it too," he said. "If we don't fairly evaluate and share this information, we're denying part of human history, we're keeping it from being studied further."

"By denying we have this proof and by not evaluating it honestly, [the archaeological establishment is] denying the Chinese people their rightful heritage. They are denying the Native American Indians their rightful heritage," Ruskamp said.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the story, a discovery in China gives the saga even deeper roots. In 2007, a scholar in China made headlines with his studies of cliff carvings at Damaidi near Yinchuan in western China. Between 500 and 800 of the 8,452 figures depicted there could be interpreted as early forms of Chinese characters. Since the rock has been dated to 6,000 BC, it would push the origins of Chinese writing back another 3,000 years, according to Endymion Wilkinson's Chinese History: A New Manual.

Contact the writer at chrisdavis@chinadailyusa.com

| John A. Ruskamp, Jr, a retired statistician who had some exposure to Chinese culture while serving in the US Navy during the Vietnam War, has found evidence that Chinese explorers roamed North America thousands of years ago, evidence like the petroglyphs, or rock art, pictured here in New Mexico. Photo Courtesy Of John Ruskamp |

| |

(China Daily 09/11/2015 page20)