Mark Lee Ping-Bing:Adding charm to film

Award-winning cinematographer of 'the most charming' gets retrospective of his work at MoMA in New York City.

For most cinematographers, unexpected weather counts as one of the most obnoxious things that can happen during a shoot.

For Taiwanese cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing, who is known for never biding his time for ideal weather, every day is good weather for shooting.

"Because reality is one of the most charming parts of film," he said.

A two-week film series called Luminosity: The Art of Cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing is being presented by the Museum of Modern Art from June 16-30 at its theaters in New York.

The program features 16 films shot by Lee from Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Chinese mainland, Vietnam, Japan, and France, as well as the North American premier of Crosscurrent, winner of the Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution at the 2016 Berlinale.

"Mark is known for his beautifully composed medium and long shots, expressive color, elegant camera movement and meditative long takes," said La Frances Hui, associate curator of MoMA's film department and organizer of the program.

"This film series intends to pay tribute to Mark's remarkable career. Also we hope to give audiences the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the art of cinematography and of course to just enjoy a group of really stunning films he made around the world with different directors," Hui added.

Born in 1954 in Taiwan, Lee, after completing his compulsory military service, took an exam for a training program at the Central Motion Pictures Company, competing with more than 2,000 people for 20 spaces. Initially placed on the waitlist, Lee was eventually admitted into the program and embarked on a journey that would change his life.

In a career that spans more than three decades, his exquisite presentation of light, shadow, color, graceful camera movement, and arresting compositions bring to the forefront cinematography's central role in the creation of motion pictures.

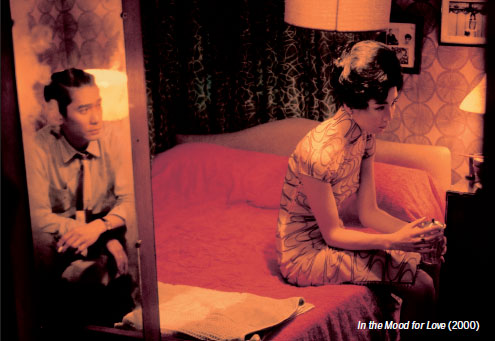

In films such as Flowers of Shanghai (1998), In the Mood of Love (2000), Springtime in a Small Town (2002), and The Assassin (2015), Lee's seductive, observant long takes mark subtle emotional transformations and inject distinctive rhythmic shifts.

Lee said it's actually very difficult to convey a lot of things in one long take, but sometimes using a long take instead of many short takes can transfer more layers of feelings and emotions to the audience.

Throughout his career, Lee has shot primarily on film and remains among a small number of cinematographers still using the medium today.

Lee is best known for his longtime collaboration with director Hou Hsiao-Hsien from A Time to Live, A Time to Die (1985) to the latest The Assassin (2015). In the 10 award-winning films they've made together, the duo has defined a vision for Taiwan New Cinema realism.

"Working with a world renowned director like Hou, it's a great honor and a great challenge at the same time," Lee said.

"I would say that pain is the thing that I remember the most, because director Hou Hsiao-Hsien is someone with really high standards," Lee joked.

"But I'm someone, who chases and enjoys pain. That's why when we work together, we create sparkle sparks," Lee added.

Lee said Hou always went forward by himself and it could get difficult for the crew to follow. "But on the other hand, he trusts people. He lets me shoot the film in my own way giving little instruction," he said.

"I worked with him on more than 10 films, and I still want to work with him on the next film," he added.

Lee has also worked with acclaimed directors from around the world, including Tran Anh Huang, Gilles Bourdos, Hirokazu Koreeda, Wong Kar Wai and Jiang Wen and his work has won him numerous international honors, including the Best Cinematography at the 2001 American Film Institute Award and Best Cinematographer of the 2010 Asian Film Award.

"Actually directors, who appreciate my cinematography and way of expression, come to me," Lee laughed.

"But I respect directors a lot when I work with them since the works are theirs," Lee said.

"When I work with different directors, I try to understand what they want to achieve and I transform it in to my way, to make the images more charming, more readable and to leave spaces for movie goers to have more layers of feelings," Lee added.

Each frame allows viewers to immerse themselves in rich visual landscapes, whether naturalistic or highly stylized.

"I think light and shadow at its most natural state is the most charming and moving state," Lee said.

"Usually, when you go on set to start shooting, things might change. And instead of sustaining the pain of waiting along with the crew, I adopt the method of just shooting and adapt to what is going on."

Li recalled the film The Sun Also Rises working with director Jiang Wen.

"Originally, we wanted to shoot in the desert in the summer to capture the inexhaustible summer scenes, but then we came across a blizzard. If we waited for the snow to melt, it would have been a week and we were running out of budget," Li recalled.

"Director Jiang was really worried and asked me what we should do. I said, it's a gift that might actually add beauty to the desert with snow and sun at the same time," Li said.

"It eventually proved to be a good idea," Li said.

Li said such things happened all the time.

"When I worked with director Tran Anh hung on The Vertical Ray of the Sun, we were shooting the scene of three sisters sitting together skinning a chicken. It was supposed to be a sunny afternoon, but it started to pour rain. I told the director that if he could keep the rain from interfering with the shooting, then we could keep moving and that's what we did."

"That scene turned out to be one of the most beautiful scenes in the film and I had been doing this successfully many times," Lee said. "That's why I dare to say that every day is a good weather for shooting."

Working and traveling throughout the world, Li has never stopped thinking about what film is, what life is and what is life for film.

Lee said he likes many western films, "like The Last Emperor, the image color and the culture captured by Western cinematographers was something I had never seen before."

"The cinematography in The Godfather, the kind of darkness suited for the gangster world, impressed me a lot," Li added.

"For me, Western films are more holistic with more layers; but for Eastern cinematography, we focus more on realism and nature," Li said.

"Film is cultural documentation, so it really shows the art and culture in the contemporary area and situation," Li said, who feels satisfied to be a recorder of our times.

(China Daily USA 06/24/2016 page11)