Economy

An uninvited dinner guest: rising prices

Updated: 2011-08-12 11:13

By Lin Jing (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

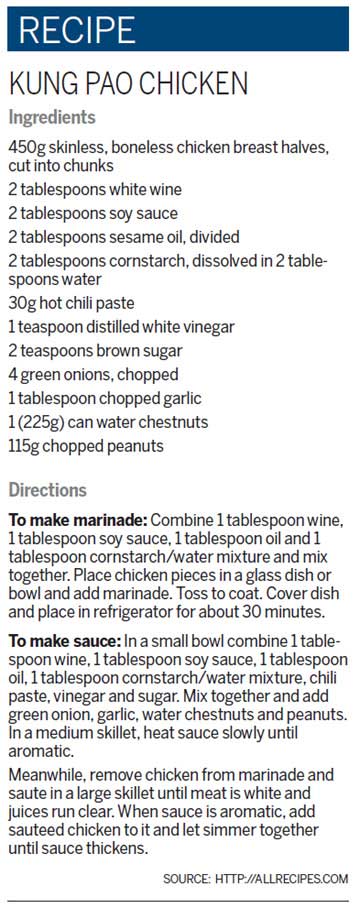

A plate of typical Sichuan-styled kung pao chicken, a venerable dish that dates back 200 years. Provided to China Daily |

If you want a good idea of how the cost of food in present-day China is rising you can do no better than popping into a restaurant and tucking into a plate of kung pao chicken, a venerable dish that dates back 200 years.

The chicken and peanut dish has its genesis in Southwest China's Sichuan province during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). It is said to be named after Ding Baozhen (1820-1886), an official in Shandong province who was later governor of Sichuan.

The story goes that Ding's favorite dish was fried chicken cubes soaked in sweet sauces, and when he was in Sichuan he often regaled his guests with this culinary delight.

Ding's title was Tai Zi Shao Bao, or guardian of the prince, but he later became known as Gong Bao, and eventually the name kung pao was bestowed on the chicken dish.

With its distinctive mix of sour and sweet flavors, the dish's popularity and fame spread throughout China and beyond. But for some lovers of kung pao something has changed with the dish in recent years - a change that has left them feeling decidedly sour.

Wang Jun, a professor at the Communication University of China in Beijing, often orders the dish when she eats out but, she says, it has become increasingly disappointing.

"Some restaurants raised the price, by 2-3 yuan (0.2-0.3 euros), and some kept the original price, but reduced the amounts (of certain ingredients), especially the good stuff. There are now fewer and fewer peanuts and a lot less chicken."

Wang sees this as a backdoor way of raising the price. But kung pao chicken is not the only dish on restaurant menus whose price has soared in recent years.

Fan Jiatong, who owns the Beijing restaurant Xue Jun, says that because of soaring inflation his gross profit has fallen from 30 percent to 25 percent in the past few months.

|

"The price of everything is going up, staff salaries, meat, peanuts and utilities," says Fan, who has had the restaurant for 12 years.

The average wholesale price of peanuts rose to 11,550 yuan a ton in July, from 7,150 yuan a ton a year earlier, a year-on-year increase of 61.5 percent, according to aptc.cn, an online information provider for agricultural products.

The retail price of peanuts is now 12 yuan a kilogram, almost double the price of a year ago.

The more expensive restaurants, with their bigger margins, have wider scope for tightening their belts and soaking up the pain that inflation causes. Emei Restaurant, which vaunts itself as "the first Sichuan restaurant in Beijing", is widely admired for its kung pao chicken. There you will pay between 33 yuan and 68 yuan for the dish, depending on the ingredients used.

But for Fan, whose target market is students and white-collar workers, the room for maneuver is a lot more restricted.

Two months ago he raised the price of more than 20 percent of his restaurant's dishes, kung pao among them, by 2 yuan. Kung pao chicken now costs 18 yuan.

"The prices for popular dishes like kung pao chicken and shredded pork in brown sauce were raised from 16 yuan to 18 yuan to cope with the growing cost," Fan says.

Of course, another way of tackling that problem would be to reduce the size of portions, but Fan says customers would be unhappy if they found they were getting less on their plates.

Last month China's consumer price index reached a 37-month high of 6.5 percent year-on-year. Food prices, which have a one-third weightage in the calculation, are regarded as the main driving force behind it.

Food costs rose 14.8 percent last month from a year ago. The price of pork, a staple food, rose nearly 57 percent over the month, the National Bureau of Statistics said.

In the past two years the prices of many agricultural commodities, including garlic, ginger and mung beans, have risen.

Over several months last year the prices of ginger and garlic rose by between 20 percent and 30 percent a month.

In April 2010 wholesale prices of garlic rose more than ten-fold, to 12.2 yuan a kilogram, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics.

The Xinhua News Agency quotes Li Jianwei, an expert on macroeconomics with the Development Research Center of the State Council, as saying food price rises have accounted for the largest part of growth in the surging CPI in the past few years.

"Our research shows that the main reason behind the price rises is increasing costs," Li says. "These include rising labor costs, increasing spending on agricultural raw materials and equipment, and higher transport costs."

And the bigger players in the market, including national and international food chains, are not immune from any of this.

McDonald's has raised the prices of some of its products nationally four times since July last year. The fourth rise was last month, with increases of between half a yuan and 2 yuan, covering best-selling products such as Chicken McNuggets, McWings and hamburgers.

Food makers, too, have raised their prices because of growing costs. Companies that have opted for cost saving by stealth - reducing the size of their products rather than increasing prices - include Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

This summer both companies gave their packaging a makeover, reducing the size of 600-milliliter bottles to 500 milliliters, but maintaining the price at 2.5 yuan. That means in effect that consumers are paying about 20 percent more.

But Wang Lei, a public relations executive for Coca-Cola in Beijing, says that rising costs are not the only thing considered when packaging is changed. Consumer behavior and distribution channels are also taken into account, he says.

Pepsi says that in an 18-month long market survey it found that Chinese buyers prefer smaller bottles.

Tingyi Holding, which makes instant noodles and beverages under the Master Kong brand, has raised the price of its noodles three times in the past year, from 2 yuan per package to 2.3 yuan.

In April last year the company reduced the size of some of its noodle offerings from 95 grams to 90 grams, or even 85 grams, to avoid raising prices. The size of Master Kong beverage bottles was cut from 500 milliliters to 450 milliliters, with no reduction in price.

"The increasing price of raw materials and fierce competition is the major reason for hidden price rises," says Chen Jing, an analyst with Beijing Orient Agribusiness Consultant Ltd, a consulting firm.

Chen says that out of a desire to keep customers and a fear of losing market share businesses are reluctant to raise prices.

"Consumers are sensitive to price changes and, if the products are replaceable, companies will not rush into a price rise. Instead, reducing the size of packaging is less noticeable to consumers."

Specials

Star journalist leaves legacy

Li Xing, China Daily's assistant editor-in-chief and veteran columnist, died of a cerebral hemorrhage on Aug 7 in Washington DC, US.

Beer we go

Early numbers not so robust for Beijing's first international beer festival

Lifting the veil

Beijing's Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City, is steeped in history, dreams and tears, which are perfectly reflected in design.