Society

Healing the split: Culture cures

Updated: 2011-06-12 08:18

By Eric Jou (China Daily)

When it was created, the Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains was a peaceful painting destined as a gift for a Taoist priest. Cang Lide looks at its tortured route before it came full cycle.

Editor's note: This piece kicks off a fortnightly spotlight on China's many treasures in its museums. These silent witnesses of the country's magnificent past all tell their own stories of art, culture, craftsmanship and the drama of daily life in peace or war.

No one imagined it would see the day when its two halves would finally be reunited as one. Throughout its rather turbulent history, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, the ink-and-brush painting by Yuan master Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), had faced fire, near destruction and then separation into two.

Huang was one of the most representative artists of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and arguably its most brilliant. He ranked among the Four Great Masters of the Yuan and was revered as their spiritual leader. Huang became a member of the Taoist Quanzhen sect after leaving his post as a court official.

It was then that he created the famous scroll, and he had meant it as a gift for the Taoist master Wu Yong. It was in this contemplative spirit that Huang captured the tranquility of the Fuchun mountains in an idealized depiction of its picturesque terrain and the Fuchun River, west of current day Hangzhou, capital city of Zhejiang province. The area's lofty peaks, tranquil rivers and bamboo-clad slopes had long been a creative refuge for Chinese poets and painters, since the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

Huang worked on this scroll on and off from about 1347 to 1350 and only completed it when he was almost 80. It became his signature work, and is known as his greatest masterpiece and a fine example in the style of the 11th-century landscape artists of south China.

The painting gained recognition almost immediately and was inspiration for many generations of later artists. But Huang was never to know his work would incite warped passion, greed and desire - all quite contrary to his Taoist teachings.

Misplaced fanaticism for this work caused the scroll to be forever torn into two sections.

In the later years of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the painting became part of the collection of the Wu family. It stayed in the clan vaults for three generations, until the time of Wu Hongyu. He loved it so much that he wanted to take it with him upon his death. There are many versions of why he wanted it burned when he died.

Some scholars theorized that Wu would rather have it destroyed than for it to be left to his progeny, whom he regarded as unworthy of the masterpiece.

Others say he was so obsessed that he wanted it as a death offering. Whatever the reason, he ordered it thrown into the fire as he was on his deathbed.

Fortunately, his nephew knew enough to snatch the painting from the flames, but the fire had already consumed an edge of the scroll and it was scorched and torn into two.

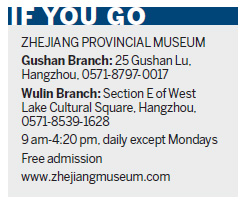

In 1652, the family repaired and reframed the painting as two scrolls. The first section, measuring 51.4 by 31.8 cm, was named the Shengshan Tu, or The Remaining Mountain. This smaller painting was eventually collected by the Zhe-jiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou and is now one of its main attractions.

The larger second section measures 636 by 33 cm.

It was named the Wuyongshi Juan, or Master Wuyong's Scroll, after the Taoist master for whom it had been originally intended. This was the section that finally ended up in the Qing imperial court in 1747, as part of the Emperor Qianlong's collection, although he was convinced that it was a copy, although an excellent copy.

This second scroll was shipped to Taiwan and became part of the collection of the Taipei Palace Museum.

In March 2010, Chinese premier Wen Jiabao made a public request for the reunion of this Chinese national treasure.

His clarion call started the ball rolling and now, the two segments of the scroll are finally being exhibited together in a collaboration by mainland museums and the Taipei Palace Museum.

From June to Sept this year, you can see this famous work at the exhibition Reunion of the Mountains and the River in the main hall of the Taipei Palace Museum.

It will be a rare reunion indeed, and hopefully, the first of many.

By Cang Lide

Specials

Wealth of difference

Rich coastal areas offer contrasting ways of dealing with country's development

Seal of approval

The dying tradition of seal engraving has now become a UNIVERSITY major

Making perfect horse sense

Riding horses to work may be the clean, green answer to frustrated car owners in traffic-trapped cities