What I do, I do to extreme to make a difference

Updated: 2015-11-21 00:05

By Emma Dai in Hong Kong(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

“What I do, I do to extreme,” says Winfried Engelbrecht-Bresges, chief executive officer of The Hong Kong Jockey Club.

“I really have a passion for horses. And for me, to have passion in what I do is really important. That’s what turned me from a football player to a horseman. That’s also why I can make a difference and achieve things.”

Arriving in Hong Kong in 1998 at the age of 43, the German native sought “a new challenge in a completely different cultural environment”. Joining the Jockey Club as executive director of racing, Engelbrecht-Bresges has been riding high as CEO since 2007.

“Hong Kong has its can-do spirit. It’s extremely competitive. But I like it because, in a way, you can achieve things,” Engelbrecht-Bresges told China Daily.

He saw the time of the handover as “the most interesting moment” to visit Hong Kong as a major shift in political environment was unfolding. “I had very similar experiences when the wall came down in Germany,” he says.

In November 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall ended the division between the capitalist West and the communist East. The transformation in Germany brought the greatest challenge of his career to Engelbrecht-Bresges. At the time, he was CEO of the governing body of German horse racing and breeding.

“When the wall came down, I had to integrate the East German racing industry with the west,” he says. “The hard part was to build a sustainable model and create solutions for people. There were 13 racecourses, but no commercially sustainable model was available to keep them all. Yet, 4,000 people were in the industry, where the administration needed only 250.”

“In one year, we came up with a practical model to integrate the administrative and regulatory structures in the German Jockey Club, and privatized stud farms, training and veterinary centers, and racecourses.

“The most challenging task was to convince the previously state-employed trainers to become entrepreneurs and to select people who were suitable to stay on.”

“It was an interesting time. I spent Tuesdays and Fridays all over East Germany,” Engelbrecht-Bresges recalls. “You talk to people who speak the same language, but with a completely different cultural background.”

Decades after exchanging his life in soccer for a career in breeding horses and racing management, Engelbrecht-Bresges is still enthusiastic. He keeps six horses in training in the Great Stables at Chateau de Chantilly. The estate, 40 kilometers north of Paris, was built in 1719 at the command of Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, who believed he was to be reincarnated as a horse.

“It’s a beautiful place in the forest. It’s at its most magnificent when the sun rises in the morning. You can see all the horses gathering. It’s fantastic.”

“Around six times a year, I go to see my horses. Last month, I had a meeting in Paris. The plane arrived at 5:30 am and I went directly to Chantilly, spent two hours with my trainer and horses and went back to the city again. If I can, I’d like to see my horses racing.”

Engelbrecht-Bresges reckons he’s lucky that he requires less sleep than most. Normally 4.5 hours will do. It helps him to lead an “extremely intense life”, including reading 700-page Buddenbrooks by Thomas Manns, one of his favorite writers, for a third time, and watching football games at 2 am. He still loves the sport. “I don’t get jet lag. I have no time for it.”

Indian PM praises Premier Li's philosophy on economy

Indian PM praises Premier Li's philosophy on economy

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

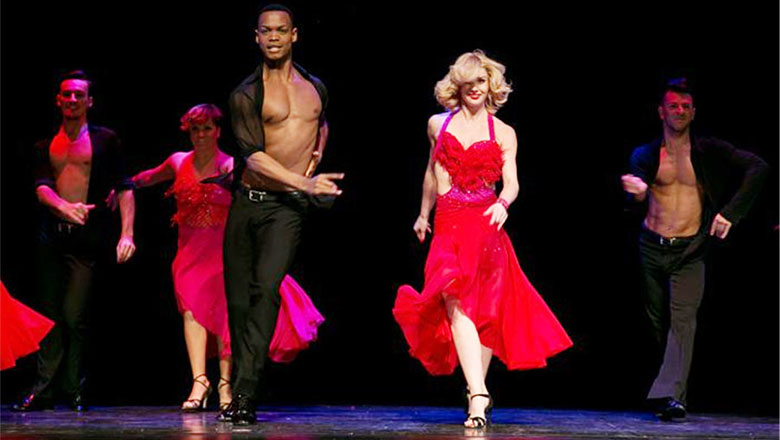

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

Xi pledges $2 billion to help developing countries

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US Weekly

|

|