Dual track

Updated: 2016-10-14 14:07

By Andrew Moody in Lhasa(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

|

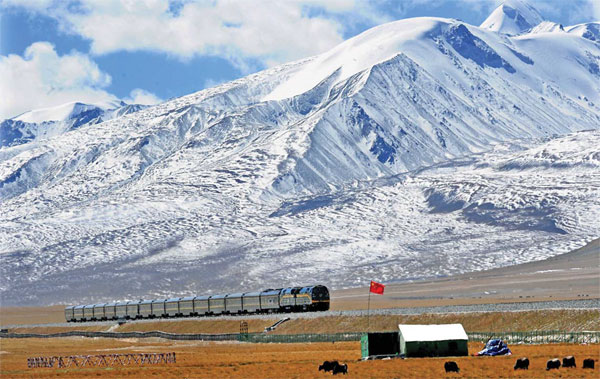

Qinghai-Tibet railway opened in 2006 and is the world's highest altitude rail route that links Tibet with its neighboring province. It will be extended to the border areas of Nepal by 2020. Wang Song / Xinhua |

For Tibet to grow and prosper, it needs to embrace modernity while retaining its unique character

With the highest altitude on Earth and mountainous terrain making all but subsistence farming impossible, the Tibet autonomous region has offered the greatest challenge for the development model that has delivered spectacular results for the rest of China over the past 35 years.

Remote, with little access to modern infrastructure and having a relatively small population of just 3 million, it was never going to be a part of the Made-in-China manufacturing success story.

Based on developing new sectors such as hydropower, agribusinesses and, in particular, tourism; and also benefiting from both the government's strategy to develop western regions as well as the Belt and Road Initiative, the region's economic fortunes are, however, changing.

In the first half of this year - along with Chongqing, China's western industrial powerhouse city - Tibet was the country's fastest growing area with GDP rising at 10.6 percent, nearly 4 percentage points ahead of the national rate of 6.7 percent.

One of the most tangible benefits has been the 83 billion yuan ($13 billion, 11.6 billion euros) investment poured into transport infrastructure over the past 20 years.

This includes the 2,000-kilometer Qinghai-Tibet railway, which opened in 2006 and is the world's highest altitude rail route that links Tibet with its neighboring province. This is to be extended a further 540 km to the border areas of Nepal by 2020.

Work has also already begun on the even more spectacular 1,629-km Sichuan-Tibet railway that will link Chengdu and Lhasa and of which 1,000 km will be in Tibet itself. It is expected to be completed in the early 2030s.

Meanwhile, there has been a major extension of the road network, ensuring that many of Tibet's most remote areas will have some access to the main highways.

The need for connectivity as well as other challenges facing the region were the focus at the recent Forum on the Development of Tibet in Lhasa.

Representatives of academia, think tanks and the media from more than 30 countries engaged in two days of debate at the Intercontinental Lhasa Paradise Hotel.

Jim Stoopman, program coordinator at the Brussels-based European Institute for Asian Studies, who was a participant in the forum, says better infrastructure is a vital issue.

"This is of crucial importance. Enhanced connectivity in Tibet is already visibly decreasing the travel time between remote villages and the major population centers," he says.

The Chinese government's Belt and Road Initiative winds its way through Tibet. The northwest is connected with the Silk Road Economic Belt and in the south, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, aiming to increase greater commercial links with its South Asian neighbors, including Nepal, Pakistan and India.

"The Belt and Road project brings clear benefits to urban areas," adds Stoopman.

"The challenge for Tibet, just like other regions along its path, is to ensure that enhanced connectivity spills over and benefits rural areas."

Although the major trade opportunities for Tibet are likely to be in South Asia, transport links open up the possibility of exporting goods to Europe.

A freight train left Qinghai for Brussels on Sept 8 carrying 44 containers with products like Tibetan tapestries and goji berries. It was the first train from the Tibetan plateau (although outside the autonomous region itself) to Europe and the 12-day journey took in Kazakhstan, Russia and Poland.

Gang Ji, partner at Roland Berger Greater China who is based in Shanghai, says infrastructure is the catalyst for Tibet to upgrade its economy.

"Finding new markets is important for Tibet since its own domestic market is quite limited because the population is small and relatively poor," he says.

"It needs not just to sell raw materials but finished goods through food processing or developing agribusinesses and better transport is vital to that. The Belt and Road Initiative should enable it to exploit its unique natural resources."

One of the central issues is whether there is an inevitable conflict between the fast pace of some of the recent economic development and preserving traditional Tibetan culture.

Sonia Bressler, the French writer and author of three books on Tibet including Voyage au Coeur du Tibet (Journey to the Heart of Tibet), who spoke at the forum, says this is an issue that absorbs Westerners more than it does Tibetan people.

"For centuries, we have placed Tibet in a perfect bubble. It has become a mythical place where we can come and recharge our batteries. As Westerners, we always see development with an evil eye claiming that it will destroy Tibetan culture," she says.

"We have to ask ourselves, what exactly is Tibetan culture? Is it only Buddhism? Is it nomadism? In Tibet, there are many ethnic groups, including Zang, Nu and Dulong, as well as other religions such as muslim and it has been this way for centuries."

Bressler, who has traveled extensively in remote areas of the autonomous region and lived among local people in austere conditions, says Tibetan people want to live a modern life like anyone else.

"Access to water, electricity and education is what we regard in Western society as essential. Why should it be different in Tibet? "

Albert Ettinger, a Luxembourg-based Tibet historian who also spoke at the forum, says there a lot of myths about Tibet.

He believes the image of it being a Shangri-la paradise was inspired by the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by British novelist James Hilton.

"He never actually went to Tibet. In the 1950s. It was a feudal and very unequal society, ridden like India to some extent with a complex caste systems.

"There were nine categories (status levels) of people. If you were someone of high standing and you killed someone of lower standing, the worst punishment you would have would be to pay some reparation. If you were of lower standing and stole something from someone higher up, you would have your hand amputated. Having your eyes gouged out was also a normal punishment."

The autonomous region still has major challenges. Some 700,000 of its citizens still live in absolute poverty on less than 2,300 yuan ($345; 307 euros) a year.

Without support from Beijing, its economy would collapse. Over the past 35 years, 90 percent of its fiscal expenditure has been met by central government.

"In many years, support from the central government has surpassed the autonomous region's actual GDP," says Yang Tao, senior researcher in the Research Institute of Society and Economics at China Tibetology Research Center in Beijing.

"Last year, aid from central government was nearly 100 billion yuan, exceeding the total output of the economy. The financial support goes into two main areas, infrastructure and improving people's livelihoods. So not much of it goes into economic production and the efficiency of it is not as high as one might expect."

This level of central government support has meant it has been able to pursue a different development model from the rest of China, which relied on agriculture first and then built a manufacturing base.

"Tibet cannot develop from an agricultural into an industrial society because it lacks people and, in particular, people with technical skills.

It also has high transportation costs because of its remoteness. Manufacturing relies heavily on raw materials and the transportation of raw materials is very costly," adds Yang.

"It does not need to follow the economic theory of transforming from agriculture to manufacturing and then to tertiary industries. It can move directly from basic agriculture to developing tourism."

Robbie Barnett, director of the Modern Tibet Studies Program at Weatherhead East Asia Institute at Columbia University, believes what the autonomous region needs is more people-centered development.

"I think we need to look seriously at other models apart from the GDP growth model," he says.

"You get this huge focus on materialistic results. It is all about numbers, what is being built and other quantitative achievements. You need to look more at who is benefiting from the economic shift, what kind of economic change people want and at what pace it should be."

Andrew Fischer, associate professor of social policy and development studies at the International Institute of Social Studies at Erasmus University Rotterdam, says one of the challenges for Tibet's development is that if people want to get out of mainly subsistence agriculture, they have no choice but to move to the cities.

"The problem is that when you move out of agriculture, there is not a lot to do in rural areas. Unlike in neighboring Sichuan or in Xinjiang, there are not a lot of economic opportunities in rural areas. As a result, the development model of Tibet has been much more urbanization-focused."

Stoopman at the European Institute for Asian Studies believes the challenge is to give those remaining in the rural areas support, even if there is an exodus to the cities.

"It is important to ensure these farmers and herdsmen, now often living isolated lives, have better access to healthcare and education in order to provide them with new skills. This would enable them to make their own decisions as to whether or not to leave the rural areas."

Although there are large reserves of minerals and extractive industries exist in Tibet, such industries suffer from a lack of transport links to take the resources to where they are needed.

Thomas Luedi, managing partner, energy and process industries for Asia at management consultants A.T. Kearney who is based in Shanghai, suggests that the region would find it very difficult to achieve the same success as the Inner Mongolia autonomous region in this field.

"Although Tibet is one of the largest copper regions in the country, the economic case for doing extensive mining there, given its remoteness, lack of infrastructure and distance to market does not really exist. There are many other areas of China that present greater opportunities to pursue. You have to ask whether it makes sense to do greenfield development with resources prices (as low) as they currently are."

Luedi says the greatest natural resource that Tibet has is its tourism and this is what it needs to develop the most. The number of domestic tourists has increased fivefold since 2007, according to the latest figures.

"Tibet has the same potential as the European Alpine valleys, the Scandinavian fjords or Kenya with its wildlife and safaris. I think much more can be done. Much of the opportunity is for domestic tourism but it could become a major international tourism area also."

For Yang at the China Tibetology Research Center, it is the Belt and Road Initiative that could transform the fortunes of the autonomous region over the next decade and longer.

"This initiative has the potential to promote economic development, investment, trade and consumption along its routes. Tibet can develop trade in the south with Nepal, India and further afield with Bangladesh and Burma," he says.

"It can also develop transit trade and be a major hub to these destinations for goods from the west of China, including Sichuan, Shaanxi, Qinghai and Gansu."

Stoopman, whose attendance at the recent forum was his second time in the autonomous region after first visiting in 2010, says the progress is already noticeable.

"Although there are clearly some challenges ahead - which mainly pertain to tensions between tradition and modernity - visible progress has been made in terms of infrastructure, poverty alleviation and access to education."

Zhang Zhaoqing, Zheng Jinqiang and Wang Keju contributed to this story.

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

- Hollande, Merkel, Putin discuss how to implement Minsk peace deal

- Pentagon vows to respond to attempted missile attacks at US destroyer near Yemen

- NASA to invite private companies to install modules on space station

- Trump accused of inappropriate touching by two women

- White House denounces terror attacks in Afghanistan

- Republican voters frown on party establishment's criticism of Donald Trump

Birthday celebration held for panda cubs at Toronto Zoo

Birthday celebration held for panda cubs at Toronto Zoo

China's top 10 enterprises by revenue in 2015

China's top 10 enterprises by revenue in 2015

Robots, 3D printed food big hit at Shenzhen Maker Week

Robots, 3D printed food big hit at Shenzhen Maker Week

Flying over the mountains in wingsuit in Zhangjiajie

Flying over the mountains in wingsuit in Zhangjiajie

Ten photos from around China: Oct 7-13

Ten photos from around China: Oct 7-13

Superheroes make surprise visit to children's hospital

Superheroes make surprise visit to children's hospital

Female soldiers take training in Hainan

Female soldiers take training in Hainan

Premier Li vows anew to ease market access

Premier Li vows anew to ease market access

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Trump outlines anti-terror plan, proposing extreme vetting for immigrants

Phelps puts spotlight on cupping

US launches airstrikes against IS targets in Libya's Sirte

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

Abe's blame game reveals his policies failing to get results

Ending wildlife trafficking must be policy priority in Asia

Effects of supply-side reform take time to be seen

US Weekly

|

|