Forged online

It's hard to know what to believe any more. Fake news, some of it preposterous, has become a scourge of the new media, often sowing discord and confusion. Wang Yuke reports.

In Hong Kong's socially and politically charged climate, some experts are voicing greater concern about fake news, which has proliferated in step with an explosion of social media.

Not so long ago, traditional media were required to observe the principles of transparency, credibility and impartiality, and news stories from press outlets were trusted to be free from personal bias and preference, said Wan Lap-man, deputy head of the Hong Kong Playground Association, who has researched the impact of social media on society. With the rise of social networking, those standards have become less important and obsolete because everyone, whether educated or not, can post whatever they want without fear of consequences for scurrilous comments.

The "fake news" problem is not new. Political intrigue and lies have always been a part of public life, while propaganda and disinformation have been disseminated throughout history. The problem today is different in that the rise of various media tools and freedom of the press make it far easier to spread lies. Fake news has greatly "evolved" with the help of social media, which enables people to plant deceptive content that reflects their own political objectives, targets like-minded readers, validates readers' bias, or attempts to sway others holding different views.

A major worry is that people will decide on their political stance and take action based on false information found on media networks. In many cases, this disinformation is intentionally proliferated to manipulate public sentiment, said Masato Kajimoto, assistant professor of Journalism and Media Studies at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). If enough people are taken in by fake content that distorts the truth and triggers widespread anger, it will cause unnecessary polarization in society. "Even the government could make poor judgments based on public reactions," he cautioned. Moreover, fake news also divides society by "harming the effort to build a constructive dialogue".

Age of unreason

According to a survey conducted by the Hong Kong Playground Association, over a quarter of youngsters below age 24 had 100 to 1,000 friends on their social media accounts and 5 percent had more than 1,000 friends. "This means that fake information online could spread easily, quickly and widely," said Wan, who led the study. Meanwhile, too many people are unconcerned with verifying posts before clicking the "share" button, Wan added.

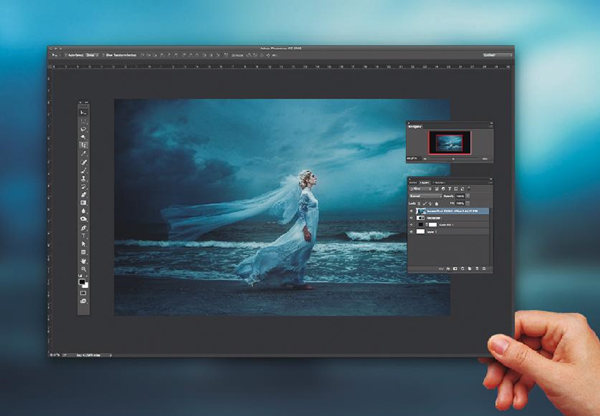

"Many young people today often are irresponsible in their posts and comments online," Wan said. Some keen to share posts that are eye-catching just to entertain their friends, even if they themselves may take them with a grain of salt. "Especially when the person concerned in an edited picture or a made-up story is a stranger, they are more likely to share or comment on it," Wan said. Secondary 3 student Sum Yik-yuk is one youngster who became overly enamored of juicy news about celebrities. She admitted that she would repost exciting rumors on Facebook, only to feel cheated after the rumors were debunked a few days later.

And yet, "We cannot afford to ignore middle-aged and older adults who have limited digital information knowledge or experience and therefore are more susceptible to misinformation," Wan said. In some ways, adolescents are better at spotting fake news content than grown-ups as they are more computer-savvy and skillful at using mobile applications, Wan explained. From experience they can easily identify a fake picture that may pass for a real one to a digitally unsophisticated adult.

Older adults have relatively small friendship circles on their social network platforms, which in theory should hinder the widespread distribution of fake news. But it is not necessarily the case, Wan remarked. "They are so familiar with each other due to long-term friendships that they trust whatever their friends post. They don't even bother to filter the information in their minds."

In the past, newspapers, television and radio were the main sources of information, so older generations may still habitually take what they read and hear on the media today as authoritative, Kajimoto said.

However, when it comes to call-to-action posts, people tend to behave more cautiously, Wan said. In other words, if a post requires the viewer to invest money, time or effort, they will spend time judging whether the information is reliable before taking action. This may be a post describing the plight of a sick child and calling for donations, or a post requiring the viewer to follow instructions in order to get a coffee coupon.

Enlisting the law

Social media have come up with solutions to counter the spread of fake content. Facebook became the first company to implement "flag" options so that users can create an alert for questionable stories that may subsequently prove to be false. If enough users flag the story, it will appear less frequently in the news feed of their friends' pages. Critics, however, still worry that activists will take advantage of the option, reporting as false any content at odds with their personal sentiments.

Wan reckons that it's time to require everyone on the city's social media to use their real names, supported by proper identification to register an account on the various platforms. This would help the sources of fake news content to be traced, he said.

The South Korean government implemented the Real Name Verification Law in July 2007. Singapore enforced mobile-phone identity registration starting from November 2005, when all mobile retailers and service providers were equipped with the Identity Scan Recognition System. Customers must put their identity card through the system before registering for new numbers. On the Chinese mainland, everyone is obliged to use a real name-registered SIM card on their mobile phones.

Wan believes that there can be no absolute freedom of speech in any society. Legal constraints, arguably, might compromise freedom, but freedom is viable only when limitations are in place, Wan contended. Regulations will help, but public education to improve citizens' media literacy is also necessary, he added.

Kajimoto from HKU agreed that to keep up with the advancement of digital technologies there is undoubtedly a more urgent need for new-media literacy. This is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and create information using multiple forms of communication, with the larger goal of creating informed and responsible citizens. Lok Sin Tong Yu Kan Hing Secondary School is one of the few schools that have experimented with a new-media literacy curriculum — Be NetWise, initiated by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups — to encourage critical thinking and to nurture new-media literacy among teenagers.

Au Ho-ming, who went through the program, said he no longer feels in a rush to share or comment on news stories if he has even the slightest doubt about them. "I'd wait and see, until the news is officially verified."

Such programs in essence aim to train youngsters to become fact checkers. That's why the school librarian was brought in to teach students how to check facts, trace news sources, and locate first-hand and accurate information.

Kajimoto has cooperated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University to develop a new-media online classroom, edX.

The six-week online course was free and open to everyone. Kajimoto was pleased to see that older adults began to show interest in learning new-media skills, with 27 percent of students who registered for the online course aged 40 and beyond. More than half of the students were between 27 and 40.

Advertorials can also be presented in the guise of genuine news today, warned Kajimoto. If a supposed news article contains a link to a certain product or service, then it could be an advertisement or promotion. He advised people to look for labels such as "Sponsored content", while assessing the validity of the web address.

Kajimoto is now concerned that media-literacy programs hold less appeal for people with lower education and lower levels of digital competency. He has found from his online portal that well-educated students and those with digital awareness predominate and are more likely to complete the entire program. He thought the reason could be that "less-educated people find it too overwhelming to pick up a host of new media skills at once".

To motivate less-educated people to take part, Kajimoto and his team are working toward making short videos, with each video dedicated to teaching one skill or two, and then posting them on social media platforms. "One skill at a time could be easier for them to digest," he said.