Raise a glass to patience

Updated: 2014-12-22 14:55

By Mike Peters(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Nicolas Potel brings premium wines made the old way to China.

This is a little embarrassing: I have a sudden, mad desire to see Nicolas Potel's bare feet.

The well-dressed French winemaker has recently opened a new warehouse for servicing his mainland clients, as high-end hotels in China's big cities seek out exciting new vintages.

|

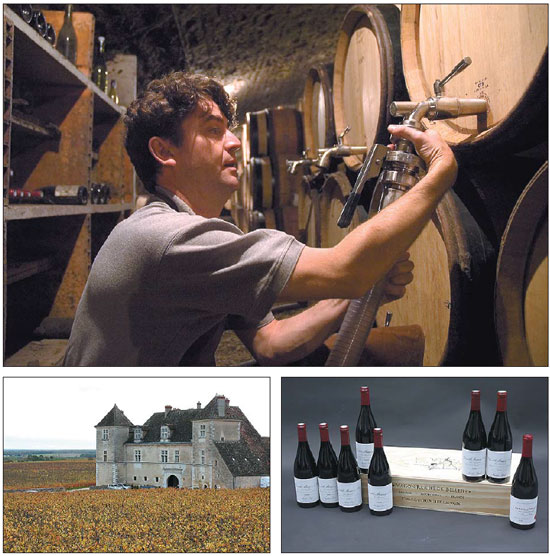

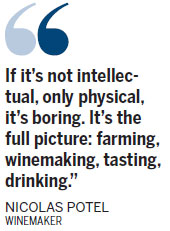

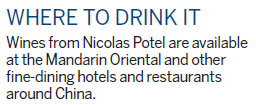

Nicholas Potel (top) approaches his wines in a very hands-on and traditional way at his Domaine de Bellene (above left). In another operation, Potel purchases grapes from other vineyards planted with vines at least 60 years old and makes wines (above right) under the Maison Roche de Bellene label. Provided to China Daily |

I should be focused on the 1995 Puligny Montrachet 1er Cru that he is about to decant. Instead I steal a glance under the table. Is he wearing socks?

Potel, chatting comfortably about terroir and such, senses nothing amiss, but his extremely proper colleague is now giving me an odd look.

I quickly put forward the question that's driving my distraction: "Do you really still stomp on grapes with your feet at your winery?" I've asked many winemakers about this, only to get a look, as if to say, how old are you?

But Potel, who was just about to get way too technical about minerals, breaks into a huge smile.

"But of course!" he says, stopping short of revealing his purple-stained soles. His hand-picked grapes, he adds, are processed in basket presses as well as by human feet.

In the fields of Burgundy at Potel's flagship estate, Domaine de Bellene, there is no mechanical harvesting. Horses pull the plows. Live chickens scratch around the totally organic vineyard, converting grass and insects into nutrient-rich fertilizer. In the winery, there are buckets to move the nectar of Bacchus from one stage to the next, not pumps. There are no electric bulbs - Potel's eyes light up as he waxes eloquent about candles. "We keep the cellar at 20 degrees," he says, "but temperature is not the only factor. Light stimulates oxidation, too."

Serious business

It might be easy to dismiss Potel as a hippie dreamer if we weren't lunching in a fancy hotel dining room and preparing to open a bottle of wine that might have consumed my entire paycheck if I'd been paying.

This is a man, however, who has assumed control of a family winery, lost the business - and the family name on the label - in a series of upheavals with rival investors that began with his father's death. Since that testing in the school of hard knocks, he is running not one but three impressive wine businesses. Beyond the new family vineyard Domain de Bellene, his Maison Roche de Bellene buys grapes from other vineyards that are at least 60 years old, producing numbered bottles of Grand Cru with his own styles. Finally, he combs the cellars of the most famous producers in Burgundy, and releases choice vintages under his Collection Bellenum.

His own vineyard was created in 2006, and Potel's wine enjoys some natural advantages in the Chinese market: It's French, exclusive and expensive. While it's not Bordeaux, the French red that resonates so strongly with Chinese consumers, it has an impeccable pedigree: Domain de Bellene was built on an 18th-century estate in the town of Beaune, renowned as the wine capital of Burgundy.

His father, Gerard, founded the Potel family wine business in the 1960s, when France was still reviving from World War II and wine-making was not always the most profitable business. There is a romance about French wine-making that suggests a constant approach that goes back centuries, but the Potels were riding a wave of change.

"After the war, under de Gaulle, the mission of agriculture was to be self-sufficient, then globally to feed the planet," says Nicolas Potel. "It was a time of chemicals and clones - we chose grape varieties that produced more grapes, instead of grapes that produced more quality."

The younger Potel feels lucky to be making wine now rather than in the 1970s, when those pressures were peaking. "The industry is not so into chemical acidification now. We have changed our ideas about vine management, and look for better compost and better soil."

Consumers have changed their ideas, too, and health and food safety have become mainstream concerns. Small wineries like his can deliver a level of quality that's beyond the business model of big producers.

'A social attitude'

Running a wine estate obviously means more than merely farming for Potel.

"It's about a social attitude to your workers, the way that you build. What's the point, for example, in growing organic vegetables and then using big trucks to move them a long way?"

Idealism is in his blood, it seems.

"My father was horrified by the development of nuclear power and weapons," Potel says. "Of course, the '60s were all about protesting against something, taking it to the street." The younger Potel says he want to channel his efforts to be FOR something, whether that means buying solar panels or energy-efficient tractors.

Potel's pursuit of soils that are naturally right - instead of "fixing" them through chemistry - is taking winemaking back to its roots.

"That's how the Romans developed viticulture 3,000 years ago," he says. "When they came to Moselle, for example, they found places to grow good grapes. As they traveled in their conquests, they didn't build roads on good growing soil."

Seeing the big picture and looking ahead are watchwords for Potel.

Europe's dairy industry took a hit several decades ago when a herbicide in wide use caused dairy cows to lose an enzyme crucial to cheesemaking. "Scientists couldn't find the cause for 20 years," he says, "until they followed the trail from grass to meat, to milk, to cheese." Potel says he wants to study vineyards the same way.

"If it's not intellectual, only physical, it's boring," says Potel of his life's work. "It's the full picture: farming, winemaking, tasting, drinking."

Making wine, he says, is simple: gather, press, vinify. "Any kid can do it," he says with a grin and a shrug. "The complex thing is to achieve a super grape and put it into the tank."

He's always felt the need to have a vision for the future, he says, because winemaking is a slow process.

"Vines planted in 2007 will take until 2030 to produce a great vintage," he says, "so it's a patient man's game. My father passed that sensibility to me, and I hope to pass that to my own son."

(China Daily USA 12/22/2014 page9)

Yearender: 10 cultural 'firsts' in 2014

Yearender: 10 cultural 'firsts' in 2014

9 things you may not know about Winter Solstice

9 things you may not know about Winter Solstice

10 most innovative cities in Chinese mainland

10 most innovative cities in Chinese mainland

The world in photos: Dec 15-21

The world in photos: Dec 15-21

Santa Claus gives out gifts

Santa Claus gives out gifts

BRICS countries upbeat on long-term growth

BRICS countries upbeat on long-term growth

Trending: Cooking hot pot in snow

Trending: Cooking hot pot in snow

Woman does Yoga in minus 30 degrees deep freeze

Woman does Yoga in minus 30 degrees deep freeze

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Nation to become net capital exporter

Beijing willing to assist Moscow

US-led strikes against IS in Syria 'ineffective'

Pyongyang denies cyberattack on Sony

Colombia weighs oil sector options

China approves modified corn import

Obama expresses condolences for NY police officers

A fruitful year for China-Brazil relationship

US Weekly

|

|