How Wang Shukun became a big bee

Updated: 2015-02-25 15:30

By Lucie Morangi(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Chinese workers are finding that adopting an African name can help strengthen bonds of trust

When Wang Shukun was studying English at the Tianjin Foreign Studies University, he adopted Eric as his given foreign name, a practice common in China for students of foreign languages.

The name was trendy, easy to pronounce and according to him, short thus easy to remember. "It only has four letters."

|

Wang Shukun, who has lived in Kenya for three years and is now a business development executive, is doing quite well as his African alter ego. Provided to China Daily |

But Wang, now 25 and working in Kenya, had no idea at the time that he would be given yet another name, an African name rich in cultural, relationship and even personal significance.

Wang is not the only Chinese in Africa who is finding that names carry great weight in the continent. It is a discovery that seems to give the lie to the assertion of Shakespeare's Juliet, who tells Romeo, "A rose by any other name would smell as sweet."

After completing his studies in 2012, Wang got a job with Tongya Automobile and enthusiastically chose to come to Kenya as its sales agent.

He was able to put his newly minted English to good use, confidently introducing himself as Eric. It cut out the time that would be needed to teach locals how to pronounce his Mandarin name, he says. "It also showed that I was already breaking the ice of cultural barriers before starting business meetings. Success was therefore easily achieved."

Unfortunately the parent company was forced to restructure its operations following the death of the founder. The four sons inherited and divided the business. Eric had his stint in Kenya cut short.

This was devastating news. Luckily, he had already made headway with the owner of Bonfide Group, whom he had met coincidentally at the hotel where the two resided. Bonfide Group has interests in sectors including clearing and forwarding, construction, leasing of heavy machinery and most recently, real estate. It was founded in 1997.

First, Wang helped when the founder was struggling to operate a karaoke machine. The next day he took him some painkillers for his toothache. A bond was immediately formed, leading to a job offer.

He initially declined, but when faced with the possibility of not returning to Kenya, he reopened negotiations. He went back to Nairobi as a special assistant to the managing director handling the Chinese portfolio. His task is to bid for Chinese business and implement these projects to completion.

His tenacity soon impressed his boss, who started referring to him by his own second name: Gichuki. "He regards me as his son," Wang says.

The name caught on fast, and soon the more than 20 office colleagues and 200 field workers called him by this name.

The name Gichuki hails from the Agikuyu, a populous community in Kenya. People are named after family members, so there is deep value attached to it. The name also means big bee, and may symbolize a very hardworking person in the community.

Besides the name, he is renowned for being a perfectionist. "I motivate workers to finish on time and deliver high standards as expected by our Chinese clientele."

This has increased customer confidence of Bonfide Group, hence improving its international image. Furthermore, his integration with the locals is good. "The name gives a sense of belonging," he says. "People say that I have successfully become one of them."

Wang, who has lived in Kenya for three years and is now a business development executive, is doing quite well as his African alter ego.

His sentiments are shared by Khadija, whose Chinese name is Xu Chen. In her perfect Kiswahili, the China Radio International correspondent says her name has earned her respect from the locals. "They are proud that I have a Swahili name," she beams.

Given to her by her lecturer 14 years ago while studying at Beijing School of Foreign Languages, her first reaction was to find out about and enjoy its meaning. "It means a hero or a pure saint," she says adding that her other two colleagues also got names with positive meanings.

She was therefore confident of bonding easily with the locals once she arrived in Kenya. Six months into her two-year stay, she is happy with her name as she easily maneuvers in the field. "They embrace me as part of them," she says.

The youthful reporter believes that having a new name does not erode one's cultural links. "The most important thing is where you live. Where you come from does not change. A new name means you have new knowledge."

She thinks that this rationale could be adopted by Chinese companies that are striving to enter the African market. She agrees that it would make them competitive and that a new, local brand name would be easy for consumers to remember.

Sales expert and business strategist Sam Kariuki says it is hard to remember Mandarin names since Africans are not used to letters such as X and Q. "It is easy to remember something that can be easily written and pronounced."

His interactions with a Chinese client with a local name are still engraved in his mind. "It was astonishing as well as refreshing. I was happy to do return business with him as his name complimented his diligence in business."

As for the view that a new name diminishes one's cultural bearings, Kariuki says that changing one's name to make others comfortable portrays great self-sacrifice and humility by the Chinese. "It shows that they can go to great lengths to make things possible hence their success in their undertakings."

Kariuki, the author of The Guy Who Fired His Boss, which encourages entrepreneurship, says the same sacrifice may have to be made by Chinese companies who want to go global. "With great sacrifice comes great rewards," he syas, referencing local companies that have recorded success by using vernacular media stations.

One counterpoint, Kariuki says, is the issue of credibility, especially when signing official documents.

But Wang says that for him there has been no downside. The name helps, but it is not everything. "People do not trust a name but the person," he says.

lucymorangi@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily USA 02/25/2015 page10)

- Greece makes more concessions to euro zone, Germany sets vote

- Portugal to enforce tighter investor visa rules after scandal

- Kiwi opposition blasts troop deployment to Iraq

- Vietnam's travel companies cash in on Lunar New Year holiday

- Eurogroup, Greece agree on bailout extension for 4 months

- Foreign workers killed in Abu Dhabi blaze

Lady Gaga, Julie Andrews notch Oscars' top social media moment

Lady Gaga, Julie Andrews notch Oscars' top social media moment

Festive dragon

Festive dragon

Riding in style

Riding in style

Chinese volunteers make the homeless feel at home

Chinese volunteers make the homeless feel at home

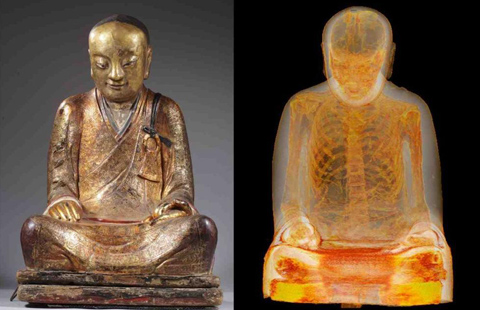

Monk's body found concealed in Chinese Buddha statue

Monk's body found concealed in Chinese Buddha statue

Lady Gaga, Julie Andrews notch Oscars' top social media moment

Lady Gaga, Julie Andrews notch Oscars' top social media moment

Restored terracotta warriors don 'scarves' and 'dresses'

Restored terracotta warriors don 'scarves' and 'dresses'

Texas Lunar Festival fun

Texas Lunar Festival fun

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese foreign minister cites key principles

Petition seeks to overturn Chinese-American officer charge

China highlights dos, don'ts in developing intl relations

Advocates optimistic on immigration

Google teams up with 3 wireless carriers to combat Apple Pay

Kiwi opposition blasts troop deployment to Iraq

It's not just the gift, but the thought behind it

Savoring benefits of medicinal foods

US Weekly

|

|