Bringing Indian businesses back from China

Updated: 2015-02-26 07:38

By Bloomberg(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants the country's companies to embrace their homeland as a manufacturing base. It's a hard sell for businesspeople like Himanshu Baid.

Baid can still make more money in China even though he pays his workers three times more than at his two factories in India, which supply the domestic market. Congestion at ports, a lack of skilled workers and a shortage of raw materials offset any advantage India has with cheaper labor costs, he said.

"It was a risk for a small company like ours, but it worked as China is an easy place for business," said Baid, head of Poly Medicure Ltd, a New Delhi-based company with an annual sales of $53 million. "It's a struggle in India."

Modi has sought to reverse those perceptions since taking office last May with a policy initiative to entice companies called "Make in India". Industry groups are now looking for him to fill in the details when his government presents its budget on Saturday.

"What India must demonstrate is a convincing vision and the means to implement it," said Jean-Pierre Lehmann, a professor of international political economy at the IMD, a business school in Lausanne, Switzerland.

"There is a lot to be done that will require profound transformation in policies, structures and attitudes."

As part of "Make in India", Modi plans to raise the share of manufacturing in the economy to 25 percent by 2022 from the current 18 percent. Doing so will create 100 million jobs, the government estimates, enough to absorb the world's largest working-age population.

In the seven decades since India achieved independence from the British in 1947, the share of industry in the economy has remained largely unchanged. Services have replaced farming as the dominant growth driver, and now account for 65 percent of the economy, according to the Finance Ministry.

While China emerged as the world's factory with manufacturing accounting for about one-third of its economy, India suffered from stifling bureaucracy that required permits to produce goods until 1991. English-language skills and an edge in information technology have allowed India to win back office business from a range of multinationals since then.

"The goal should be to strengthen Indian manufacturing so it can stand on its own and compete effectively in domestic and world markets," said Eswar Prasad, a former chief of the International Monetary Fund's China division and now an economics professor at Cornell University.

"Compared with China, India has a cheaper and younger workforce that could boost the country's attractiveness to foreign investors."

Modi has taken some steps to make it easier for companies to do business, including moving the application process for industrial licenses online. Investors planning to set up a factory can leave queries on the "Make in India" website and they will be answered in 72 hours.

Still, much more needs to be done. India fell to 142 of 189 countries on the World Bank's latest Ease of Doing Business Index, falling behind Ethiopia, Yemen and Sierra Leone. China improved several notches to 90th on the index.

It still takes 30 days and 12 clearances to get a company registered in the industrial hub of Noida, near Delhi, for instance, according to the World Bank - three times longer than it takes on average in the 34-member grouping of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Modi's administration must clean up a maze of tax rates in which rates for components in some sectors are higher than those for the finished product. Business groups are also calling for the end of the minimum alternate tax, which offsets any financial incentives exporters get from investing in special economic zones.

Attracting investment is key for Modi to provide jobs for the 64 million new entrants to the jobs market in the five years ending 2016. By 2021, almost two-thirds of its 1.2 billion people will be of working age, according to the Finance Ministry.

As India becomes more productive, it will be in a better position to compete with China. By 2020, India will have an average age of 29 years old, eight years younger than China.

Manufacturing share in output surges when a country's average income in terms of purchasing price parity is about $5,000 and peaks at $10,000, according to a study by McKinsey and Co.

India's per capita income is $5,850, while in China it is $11,850, according to the World Bank.

|

A warehouse of a logistics company in Huaibei, Anhui province. Although the country’s labor costs are rising, many Indian businesspeople still regard China as an easy place to operate. Xie Zhengyi / For China Daily |

(China Daily USA 02/26/2015 page16)

Chengdu citizens visit Du Fu Thatched Cottage to mark Human Day

Chengdu citizens visit Du Fu Thatched Cottage to mark Human Day

Tencent gifts red envelopes to employees

Tencent gifts red envelopes to employees Throwing coins to please God of Wealth

Throwing coins to please God of Wealth

7 companies that aim to fly high with drone deliveries

7 companies that aim to fly high with drone deliveries

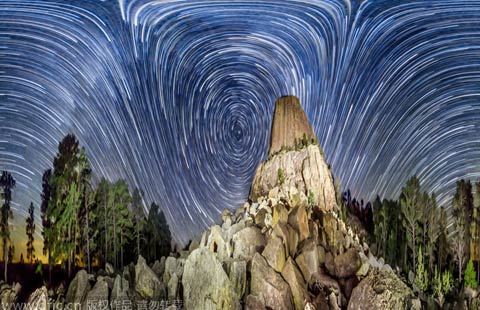

Starry Night created by lens

Starry Night created by lens

Dragons, martial arts and basketball

Dragons, martial arts and basketball

Stringing in the New Year

Stringing in the New Year

Top 10 Chinese innovators in 2014

Top 10 Chinese innovators in 2014

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Obama blames immigration woes on Republicans

New fighter jet ready for PLA

Why China's youth is getting the needle

Most Chinese forced to return home were living abroad illegally

US State Dept calls for cyber security boost

Anbang buys new piece of Manhattan

California here we come: Chinese

Port dispute over, shelves take time to restock

US Weekly

|

|