Frank H. Wu: 'Stand-up' activist, educator

Updated: 2015-03-20 12:16

By Lia Zhu in San Francisco(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

"It's not fair."

When Vincent Chin, a young Chinese American, uttered his final words before he was bludgeoned to death by two white autoworkers in 1982's Detroit, Frank H. Wu, a then-15-year-old boy living 12 miles away, was unaware of the impact the murder would have on his life.

The once prosperous Detroit fueled by the auto industry was undergoing economic anxiety due to global competition and the oil crisis in the 1970s, which resulted in racial tensions as whites blamed people of Asian descent for taking away their jobs. Vincent Chin was a victim of that prejudice.

"When I was a kid growing up, on the playground at school, every day I would be called 'chink,' 'jap' or 'gook' and challenged to karate," recalled Wu, now chancellor and dean of University of California Hastings College of the Law.

After his father was hired by Ford Motor Company as an engineer, the family moved to Detroit in the 1960s, where he spent most of his childhood feeling "unusual".

Wu said he took this as "common childhood cruelty." Like most kids, he just wanted to fit in.

Were it not for the Vincent Chin case, "I would have never talked about issues like race, or civil rights," he said.

"I remember the haunting photograph of a smiling, fresh-faced Mr Chin, shown repeatedly in newspapers and on TV, and the tears of his mother, Lily Chin, who lamented that his killers had escaped justice. Mr Chin was buried on the day he was to have been married," Wu wrote in an article published in 2012, the 30th anniversary of Chin's death.

"This case was - not just for me, but for many people - an awakening," Wu said. "It made me realize how important it is to stand up and speak out, and protest injustice."

Civil rights activist

From 1995 to 2004, Wu taught law at the historically black college Howard University, where he developed as a thinker and wrote about topics such as civil rights and civil liberties, affirmative action and multiracial identity.

"I was surrounded by Afro-Americans. I saw that I enjoyed privileges. It's easier for me to walk down a street than for a young black man. Nobody really thinks that I am a thug, a purse-snatcher or a murderer. Because I'm Asian, they think I am a genius or a concert pianist," Wu said.

In his book Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White, published in 2002, he argues that the "model minority" myth - Asian-Americans as overachieving nerds - persists.

"Asian Americans were seen as model minorities, we were also perpetual foreigners. Taken together, these perceptions can lead to resentment. And resentment can lead to hate," Wu wrote.

Wu pointed out three steps for Chinese Americans to strive for equality: stand up and speak out; build bridges to others, and organize.

"Chinese Americans first have to admit there's discrimination. Sometimes it is embarrassing to admit someone has been mean to you, or unfair," Wu said. "It takes guts to do that."

"For many Asian immigrants, who come from a culture where you are not supposed to make waves, the first step is to get angry and feel empowered, to think: 'This is wrong, you can't do this to me'," Wu said.

The second step is to build a bridge to others who face similar issues to this, and this means reaching out to someone who's Japanese, Hispanic, black, Jewish, or Arabian, according to Wu.

"Historically, Japanese hate Chinese and Chinese hate Japanese. But here in America, Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans have come together."

"It doesn't matter Chinese and Japanese don't like each other. Here we have a common cause, a mutual defense," he said.

It might be from the Chinese cultural influence of teaching being a high calling that Wu went back to law school as a teacher after two years' practicing law in San Francisco.

Visionary educator

"When you are a lawyer, you represent a client, and you don't advocate on your own beliefs, or what you truly believe," Wu said. "I enjoyed practicing, but I always knew I wanted to be a law professor. I want to change the world."

After having taught at Howard University for nine years, Wu returned to Detroit in 2004 to serve as dean of Wayne State University Law School at age 37, becoming the first Asian-American law school dean and also the youngest law school dean in the country at that time.

"I wanted to go back to Detroit to do something helpful. I enjoyed being in Detroit, which's an important part of who I am," he said.

However, he realized that Detroit has some deep-seeded, structural problems at a time when it continues to decline because American cars aren't as popular as they were.

"If you are a law school dean, and you are good and trying to be helpful, it's very hard to change anything. It takes cooperation and community," he said.

In 2009, a scholarship brought him to teach at the Peking University School of Transnational Law in south China's Shenzhen for the inaugural year as a CV Starr Foundation visiting professor.

Viewing the chance as "an adventure," Wu said he wanted to go to a place where there was a sense of community and mission. "I lived on campus so I got to know the Chinese students much more than I would here (UC Hastings). The students were great. They were so dedicated," he said.

When he took office as chancellor and dean of UC Hastings in July 2010, Wu put forward a plan of rebooting legal education by reducing the overall enrollment while actively recruiting students from China and other Asian countries, to prepare lawyers who function within a global economy with a trans-Pacific emphasis.

Looking out of the window, Wu said, "Twitter opened up about two blocks from here. There are all these tech companies. However, 10 percent of technological breakthrough is based on law."

"If you don't have intellectual protection, if you don't have patent law, you can't say this idea is mine. If you don't have a stock market functioning properly, you can't make an initial public offering and attract investors," he said.

"I believe in the rule of law, which is what makes this democracy great. But that doesn't mean we need this many lawyers. The number of lawyers we have is too many. So I'm trying to get this down to the right number," he argued. "But rebooting legal education is much more than class size, it's about skills training through critical programs. We have clinics where students work with start-ups, non-profit organizations and national security cases."

In January, the college launched East Asian legal studies program which provides the students with a chance to study the laws of China, Japan and South Korea.

According to Wu, graduates have been put into law firms in Tokyo and Shanghai and other major Asian cities. Efforts have also been made to recruit students from there too.

Wu is working on a new book, a sequel to Yellow.

"I want to tell more than the story of the Vincent Chin case. I want to tell stories that capture and represent the time and place that explain how the death of Vincent Chin gave birth to Asian Americans," he said.

Before the case of Vincent Chin, people didn't call themselves Asian Americans, he said. They didn't have a pan-Asian sense and they didn't emphasize American. But the Vincent Chin case pointed out how important it was for people of Asian descent to assert "we are Americans, we've put down roots here".

liazhu@chinadailyusa.com

|

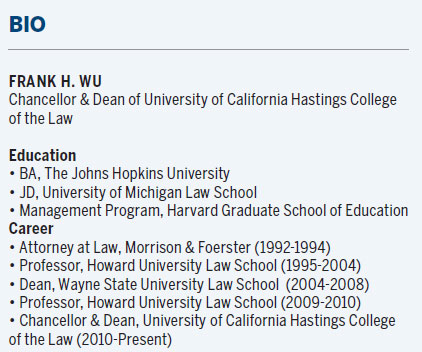

Frank H. Wu, Chancellor & Dean of University of California Hastings College of the Law. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily USA 03/20/2015 page11)

How much do world leaders earn?

How much do world leaders earn?

Daredevil ropejumpers leap 200 meter off cliff

Daredevil ropejumpers leap 200 meter off cliff

Harley motorcade shows up in Boao, Hainan

Harley motorcade shows up in Boao, Hainan

Ming art sets Christie's high

Ming art sets Christie's high

Stolen-phone bromance blossoms in China

Stolen-phone bromance blossoms in China

Prince Charles, Camilla get royal tour of Washington

Prince Charles, Camilla get royal tour of Washington

Should selfie sticks be banned?

Should selfie sticks be banned?

Tunisians demonstrate against terrorism

Tunisians demonstrate against terrorism

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Yahoo to exit from Chinese mainland market

US sends 'green' mission to China

Sticking it to the selfie stick

China's eco-friendly companies stand to gain

China's global image on rise

3 killed in shooting at California convenience store

More Chinese film companies tap into Hollywood

Microsoft tackles China piracy with free upgrade to Windows 10

US Weekly

|

|