Xinjiang: Productivity versus pollution

Updated: 2015-03-20 14:27

By Gao Bo(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Farmers in China's arid western regions have long regarded plastic film as a boon for business, but the environmental problems resulting from its use are prompting scientists to look for alternatives, as Gao Bo reports from Urumqi.

For the past three decades, farmers in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region have been masters at using polyethylene film to boost crop yields and reduce the incidence of disease, but now the material is coming under increasing fire from environmentalists and agro-economists who say it causes more problems than it solves.

In many parts of the world the material is used as a cheap alternative to glass greenhouses, but in Xinjiang, the farmers use a "plastic mulch" technique in the cultivation of more than 20 crops, including cotton, corn, and tomatoes. Huge swaths of sheeting are laid on the ground and then pierced at regular intervals to allow crops to be planted.

|

PE film is widely used in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region to improve water retention and maintain constant temperatures at root level, which are crucial factors in a region that includes a large section of the Gobi Desert and thousands of hectares of arid land. However, pollution concerns have encouraged scientists to look for alternatives. Photos by Gao Bo / China Daily |

|

Farmers in Aksu, Xinjiang, level soil covered by PE film before sowing cotton seeds. |

|

Extra-wide sheets of film are used in Alaer, Xinjiang, to reduce the amount of PE film used, and improve the land-utilization rate. |

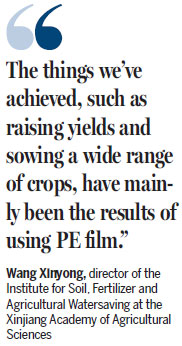

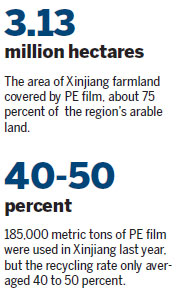

Wang Xinyong, director of the Institute for Soil, Fertilizer and Agricultural Watersaving at the Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, said the film improves water retention and helps to maintain a constant temperature at root level, which are crucial factors in a region that includes a large section of the Gobi Desert and thousands of hectares of arid land. PE film is used on more than 3.13 million hectares, about 75 percent, of Xinjiang's farmland.

Other benefits include effective prevention of weed growth and a reduction in the level of alkalinity in the soil. Along with the development of drip irrigation techniques, PE film has long been an important factor in the region's agricultural sector, Wang added.

"The things we've achieved, such as raising yields and sowing a wide range of crops, have mainly been the results of using PE film," he said. "We'll be reliant on the film for a long time to come."

A double-edged sword

Despite its undoubted benefits, PE film has proved to be a double-edged sword because the sheets are often left in the fields, and its longevity - it takes from 200 to 300 years to degrade completely - has resulted in polluted land and homes.

Wang Xuenong, director of the academy's Institute of Agricultural Mechanization, said the problems have been ignored because the benefits have been so great. "Agricultural technology has developed greatly and yields have risen year after year, so the farmers have turned a blind eye to the drawbacks of using residual film, which actually raises costs and can effectively reduce yields."

When used on thin-layered soil, the film can suffocate buds and restrict root systems, lower the budding rate and retard subsequent growth. Moreover, water and fertilizer may remain on the film and fail to reach the roots, and farmworkers waste valuable time cleaning plows fouled by strips of discarded plastic.

"When we conducted research in the rural areas, we discovered that cattle and sheep died after eating fodder containing shreds of PE film," said Wang Xuenong.

In the early years, cotton planters collected the unwanted plastic by hand after the harvest and then burned it along with the unwanted crop stalks, but the practice was inefficient and expensive in terms of labor, so it died out as farmers looked to lower costs.

That move was partly responsible for the region's low PE film recycling rate. Last year, 185,000 metric tons of sheeting were used in Xinjiang, but the recycling rate only averaged 40 to 50 percent, according to data from the regional agricultural department.

In a bid to encourage recycling, the region introduced new regulations on PE film for agricultural use from Dec 1, upgrading the standard thickness of 0.008 millimeters to a more-robust 0.01 mm.

"The thicker the film, the easier it is to recycle because it breaks less easily," Wang Xuenong said.

Government subsidies

During the past decade, the institute has been developing machines to collect film discarded in cotton fields, and one of its designs - part thresher, part plastic-retrieval system - has been actively promoted.

"The government gives farmers a subsidy of 15,000 yuan ($2,400) when they buy one, almost one-sixth of the price," Wang Xuenong said. "So far this year, we have already received orders for 40 machines. As long as the film meets the new standards, the machine can collect nearly 90 percent of the used film if the ground has been cleared, and about 83 percent if the film was buried in the soil before the stalks were cut," he said.

Last year, the regional government chose Manas, a county in north Xinjiang, as an experimental area. Manas was chosen because PE film is used in the cultivation of cotton, corn, tomatoes and peppers on more than 85 percent of its 66,000 hectares of arable land. During the experiment, films of different thicknesses were tested to enable scientists to determine the optimum thickness for recycling and durability.

To encourage the use of the thicker 0.01-mm film, which raises the coverage cost to approximately 202.5 yuan per hectare, the local government offers farmers a subsidy of 255 yuan per hectare, said Bao Yuqin, the county's chief agro-technician.

Shi Changming, a 55-year-old farmer from Manas who has used PE film to grow cotton for decades, said the subsidy and his experience of "white pollution" prompted him to use the thicker film.

"Initially, we crushed the plant stalks and then plowed them into the ground along with the discarded film," he said. At first there were few problems, but the downside soon became apparent: Ribbons of plastic sheeting were carried into the village by the winds, and they also fouled plows so badly that the farmers were forced to clean them by hand every few hundred meters, he said.

Bao said the local government has now extended efforts to promote the use of thicker film by offering the subsidies to recycling stations and manufacturers that use the recycled plastic.

This year, Manas expects to see the recycling rate for film used in fields exceed 85 percent, and film used to build greenhouses will be fully recycled.

Although he welcomed the news, Wang Xuenong was concerned about the operations of factories that use recycled film as a raw material: "The retrieved film is often mixed with stalks, soil and other things, but the factories don't have the machinery to separate them. The job requires a lot of effort and uses a huge amount of water," he said. "Without government support, the factories may not stay in business for very long, and if they fail the whole recycling chain will break down."

Biodegradability

At the institute in Xinjiang, Wang Xinyong and his team have been looking into ways of reducing the environmental impact of PE film by using polyester and starch-based materials to produce plastic sheets that will biodegrade at a much faster rate.

According to Sun Jiusheng, a member of the research team, successful tests have been conducted using crops such as cotton, potatoes and tomatoes in the prefectures of Bortala, Changji and Aksu, and will soon be extended to a range of other plants. "Right now, we're trying to reduce costs and are applying for government subsidies so we can refine the material," Sun said.

"We knew that polyester film could be degraded, but it wasn't possible to accurately control the degradation period. We experimented by adding starch-based materials and eventually succeeded in doing that."

It took five years of experimental work in a 53,000-hectare cotton field in Bortala prefecture, but the team finally came up with a technique in which PE film was treated with a catalyst that accelerated the degradation process and shortened it to just 100 days. Although it's a promising development, the treatment is still undergoing tests and is unlikely to be available commercially anytime soon.

However, in 2012, the team started another round of experiments in a potato field in Baicheng, Aksu prefecture, and developed a formula for a coating that caused PE film to degrade completely within two years in the 40-hectare test area.

"First, the film breaks into tiny pieces, and degrades 80 percent in the first year. The remainder adheres to the soil, but doesn't harm the crops," Sun said.

Although the treated film, manufactured by a company in Guangdong province, has been available for some time, it hasn't been the success its creators had hoped. Once removed from the test site, the film underperformed because the degradation process was influenced by a number of unforeseen factors, including the type of crop under cultivation, temperature, humidity and soil salinity.

Now the research team is testing different formulas on different crops in the north and south Xinjiang.

If the problem can be ironed out quickly, the manufacturer will begin producing PE film treated with the new formula, according to Sun, who added that the team plans to open its own factories in a number of prefectures.

The treated film will be expensive to produce - 40 yuan per kilogram, almost three times the cost of the untreated variety - but Sun is convinced it will be successful.

"Although the cost may be lower in full-scale production, we will still need government support, such as subsidies, to promote the film. However, this technology could be in widespread use within five years if the government gives it the backing it deserves."

Contact the writer at gaobo@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily USA 03/20/2015 page5)

How much do world leaders earn?

How much do world leaders earn?

Daredevil ropejumpers leap 200 meter off cliff

Daredevil ropejumpers leap 200 meter off cliff

Harley motorcade shows up in Boao, Hainan

Harley motorcade shows up in Boao, Hainan

Ming art sets Christie's high

Ming art sets Christie's high

Stolen-phone bromance blossoms in China

Stolen-phone bromance blossoms in China

Prince Charles, Camilla get royal tour of Washington

Prince Charles, Camilla get royal tour of Washington

Should selfie sticks be banned?

Should selfie sticks be banned?

Tunisians demonstrate against terrorism

Tunisians demonstrate against terrorism

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Yahoo to exit from Chinese mainland market

US sends 'green' mission to China

Sticking it to the selfie stick

China's eco-friendly companies stand to gain

China's global image on rise

3 killed in shooting at California convenience store

More Chinese film companies tap into Hollywood

Microsoft tackles China piracy with free upgrade to Windows 10

US Weekly

|

|