Scars spur battle over Okinawa's 'war relics'

Updated: 2015-08-12 07:44

By Cai Hong and Shan Yi in Tokyo(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Activists say rest of Japan should share island's heavy burden

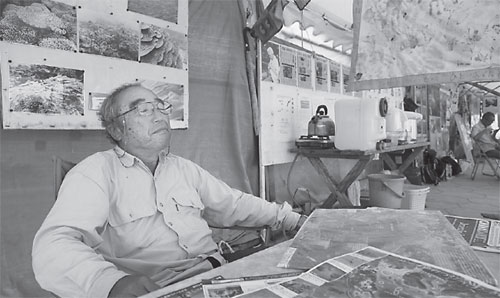

A simple tent sits by the seashore in the Henoko district of Okinawa's Nago city. Nearby is the area in the city of Ginowan that has been designated as the new base for US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

Hiroshi Ashitomi, one of the leaders of a group that opposes US military bases, calls the tent the headquarters of like-minded activists.

A wall of the tent is covered with photos of marine creatures native to the area. The activists say the new base will damage the marine ecosystem.

"The crystal-clear ocean is home to beautiful corals and is the most northerly natural habitat for the rare species of dugong, a manatee-like marine mammal," Ashitomi said, pointing to the place where a landfill project will soon be underway for the new base. "We should all strive to protect Okinawa's precious natural environment.

"This area, with a picturesque seaside and a good range of marine creatures, should be developed for sightseeing rather than a US military base."

At least 10 volunteers come to the headquarters with their lunchboxes each day, keeping a close eye on how the land reclamation is going.

Before retiring from public service, Ashitomi was a volunteer in the anti-military bases movement. He has worked hard to try to free Okinawa of such US bases for 18 years.

In the eyes of many living in Okinawa, World War II has never ended.

That is how it is for 90-year-old Masahide Ota. As a high school student, he was drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army as a member of the Blood and Iron Student Corps.

The corps was organized just before US troops invaded the southernmost part of Japan on April 1, 1945. He survived the three-month battle that the US later called the bloodiest in the Pacific War.

Ota, who governed Okinawa in the 1990s, sees the US military bases as a war relic.

The severity of the Battle of Okinawa is clear from the heavy casualties, as described in the book The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa 1945 - The Last Epic Struggle of World War II, by US writer Bill Sloan.

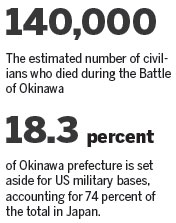

When the shooting finally stopped, Sloan writes, the bodies of 107,539 Japanese soldiers were counted. US losses totaled 12,274 dead and 36,707 wounded in combat. The number of local civilians killed, many by their own hands as ordered by Japanese troops, is estimated as high as 140,000, or nearly one in every three of the island's residents in 1945.

Peace park

Mabuni Hill in Itoman, a city in south Okinawa, where the last battle was fought on June 23, 1945, has been turned into a peace memorial park with rows of stones engraved with the names of all the war dead, be they Japanese or US.

An annual memorial service is held on June 23 in the park, and Japan's prime ministers have shown up. It was a scorching hot day when people gathered this year to pay homage to their relatives who died.

The ceremony turned rowdy when protesters told Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to "go home".

Their anger stems from the fact that 70 years after the Battle of Okinawa, the prefecture still bears the burden of a large US military presence. At the ceremony, Okinawa's Governor Takeshi Onaga broke from tradition by reiterating his opposition to the relocation of US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Nago in Henoko.

Abe talked with Onaga for only five minutes before returning to Tokyo. In 2013 and last year, he attended the memorial ceremony and chatted with then-governor Hirokazu Nakaima over lunch before heading back to Tokyo.

The political back-and-forth between Okinawa and Tokyo continues, with no real prospect of a breakthrough.

Located south of Kyushu, Okinawa represents just 0.6 percent of Japan's land mass. But 18.3 percent of this 100-kilometer-long prefecture is set aside for US bases that account for 74 percent of US bases in Japan.

Numerous accidents and crimes involving US military personnel have instilled a sense of fear among locals. The 1995 rape of a 12-year-old girl by three servicemen intensified local opposition to the US presence.

Many Okinawans are frustrated by a fate they cannot control.

Initially, Okinawa was to be used as a launchpad for the planned invasion of the Japanese main islands in the closing days of World War II.

Two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki made the invasion unnecessary, leaving a large contingent of US forces stationed on Okinawa with a huge stockpile of military hardware.

Okinawa was put under US administration in line with the San Francisco Peace Treaty that Japan and some Allied countries signed in 1951. The US and Japan inked the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security in 1960, allowing the US to keep forces in Japan.

The end of the war offered local people nothing but frustrations.

The acquisition of the land for bases, which started in 1958, was forced, with the troops brandishing bayonets and bulldozers.

'A hard life'

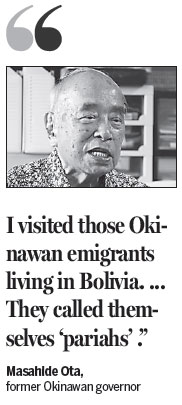

Some farmers who lost their land were compelled to move as far away as Bolivia, looking for places for permanent residence, or to work in odd jobs, according to former Okinawan governor Masahide Ota.

"I visited those Okinawan emigrants living in Bolivia. They lived a hard life there, reclaiming the barren hills for farming. They called themselves 'pariahs'," Ota said.

In 1972, Okinawans finally got what they had long sought when Okinawa prefecture was returned to Japanese control.

While the Okinawans did not harbor any illusions that the bases would be eliminated altogether, they did expect that the burden would be reduced and at least made comparable to that shared by the mainland.

But they soon learned that the US bases would remain intact. Okinawa became the military linchpin in the US strategy of Cold War containment in the Asia-Pacific region.

Many Okinawans were embarrassed when, for the first time, they asked their compatriots in other parts of Japan to share some, if not all, of their burden, Naomi Jahana, on the editorial board of the Naha-based Okinawa Times, recalled.

"We did not have the heart to transfer our suffering to others. But we were enraged after learning that the rest of Japan refused to house US bases," Jahana said.

She argued that if US military bases were essential to Japan's security, the burden should be shared equally among the country's other 46 prefectures, and Tokyo should afford Okinawa the same treatment it accords other prefectures.

The relocation of the Futenma base to Nago has caused a flare-up of the confrontation between Okinawa and the Japanese government. Located in the center of Ginowan, Futenma puts at risk 100,000 citizens who live around it.

In 1996, Tokyo and Washington reached an agreement to relocate Futenma within Okinawa. It was only in 2012, after Abe pledged to inject 300 billion yen ($2.4 billion) into the Okinawan economy each year until 2021, that then-Okinawa governor Hirokazu Nakaima sanctioned the landfill project for the base construction in Henoko. This move cost Nakaima his job.

Local election results underscore the anti-base sentiment. In November, anti-base campaigner Takeshi Onaga won the election for governor in a landslide victory. In the Nago mayoral election in January, Susumu Inamine won with a vow to oppose the base relocation.

Contrary to belief, many Okinawans say, the local economy is not dependent upon the base. The prefectural government in Okinawa argues that the US bases are a disincentive for growth. Studies found that revenue related to the US military presence declined from 15.5 percent of the local economy in 1972 to 5.3 percent in 2008. Tourism, on the other hand, has developed quickly.

Per capita income in Okinawa has always been the lowest among Japan's 47 prefectures, and its jobless rate has been the nation's highest for years.

Tokyo and Washington put forward many arguments in defense of Okinawa's bases.

Washington believes its location - Tokyo, Taipei, Shanghai, Seoul, Pyongyang and Beijing are all within a 2,000-km radius - makes Okinawa the "cornerstone of peace and stability in East Asia". Tokyo similarly sees Okinawa's role as crucial for the Japan-US alliance and believes that transferring these bases off the prefecture would strip Japan of its deterrent.

The Japanese government has stressed this point further under the pretext of a rising China being a threat to Japan.

However, many Okinawans don't buy these claims.

Hiroshi Ashitomi said that Okinawa is a peace-loving place and that the US presence has ruined its image. The US sent its soldiers from the island to battlefields in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

'Friendly ties'

"Though we don't want to be involved in wars, Okinawa may be deemed a terrible island by people in those countries," Ashitomi said. "Okinawans don't want to join the US military operations or assume the burden of US wars."

As Okinawans see it, the US marines can be deployed anywhere in the Asia-Pacific region, be it Guam, Hawaii or mainland Japan. In their view, it is not essential that the corps should be stationed on their island.

Ashitomi said Okinawa does not want to get involved in the US conflict with China. "Sitting geographically close to China, mainland Japan and Southeast Asia, the island aspires to develop friendly ties with all of them," he said.

Okinawa wants a peaceful environment, he said. The anti-bases activists oppose the shift of Japan's security policy, which they say will drag the country into armed clashes.

"With memories of the war, we know how horrible a war is. We don't want Okinawa to be a battlefield all over again," Ashitomi argued.

Many Okinawans feel that the rest of Japan owes them a debt of gratitude and that the Japanese government owes an apology to the prefecture for what its residents have suffered.

The white beach where many US troops landed 70 years ago is now rated among the most beautiful and popular tourist beaches in the Pacific.

The city of Naha, left in ruins by US incendiary bombs and high-explosive shells, has risen from the ashes to become a gleaming finance, education and political center.

Its Kokusai Dori entertainment district - teeming with restaurants, nightclubs, bars and gift shops - stretches through the heart of the city, drawing visitors from across Japan and the Pacific Rim.

But among all the glitz, local people's war scars lie deep in their hearts. They are resolved to fight back against what they perceive as Tokyo's discrimination.

Contact the writers through caihong@chinadaily.com.cn

|

People gather to pay homage to their relatives at a peace memorial park in Itoman, where rows of stones are engraved with the names of those who died during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. |

|

Hiroshi Ashitomi, a group leader who opposes US military bases, rests at his headquarters in a tent in Nago in front of photos of local marine life. Photos by Cai Hong / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 08/12/2015 page5)

The world in photos: Aug 3-9

The world in photos: Aug 3-9

'Most beautiful road on water'

'Most beautiful road on water'

Ethnic groups celebrate the Torch Festival

Ethnic groups celebrate the Torch Festival

Ten photos you don't wanna miss (Aug 3-9)

Ten photos you don't wanna miss (Aug 3-9)

30 historic and cultural neighborhoods to visit in China

30 historic and cultural neighborhoods to visit in China

Beijing Museum of Natural History unveils 'Night at the Museum'

Beijing Museum of Natural History unveils 'Night at the Museum'

Sun Yang wins third consecutive 800m free gold at worlds

Sun Yang wins third consecutive 800m free gold at worlds

Aerial escape

Aerial escape

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Govt encourages people to work 4.5 days a week

Officials to pave way for Xi's visit

China, US to exchange officials for Xi's visit

State Council approves plan to overhaul SOEs, claims report

S. Korean president mulls whether to join China's war anniversary

Sun Yang is no-show for 1,500 free final at worlds

China willing to work with US to contribute to world peace, stability

China asks further investigation on MH370

US Weekly

|

|