Not your father's Chinese restaurant

Updated: 2015-08-21 10:49

(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

They may not all offer General Tso's chicken and egg foo yong, but some eclectic Chinese restaurants in the US are serving the same authentic food that you would find in Beijing and Shanghai, HEZI JIANG reports from New York.

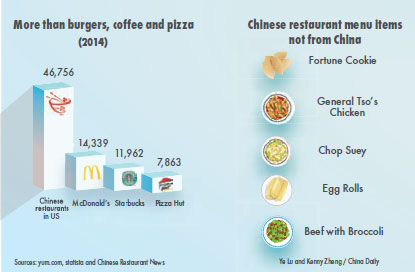

C hinese restaurants are evolving in the US, drawing their inspiration from the homeland and fusion trends and relying less on typical Chinese-American fare such as chop suey and egg rolls.

While General Tso's and sesame chicken largely remain, and the all-you-can-eat buffet places proliferate, many Chinese restaurateurs are attempting to redefine the cuisine in America, according to Yong Chen, professor at the University of California-Irvine and author of Chop Suey, USA: The Rise of Chinese Food in America.

"Chinese restaurateurs have been trying to offer Chinese food as fine dining; but their efforts have remained largely unsuccessful until recently," Chen told China Daily. "In the past two decades, such efforts have become more visible."

Chen added that "more professionally trained chefs and more affluent and more informed diners in Chinese restaurants" are helping drive the trend.

Going global

In June 1996, Wang Gang and his wife, Liang Li, opened their first restaurant, Meizhou Dongpo, in Beijing. "Someday we are going to cook for the whole world!" they said.

Nineteen years later, they oversee a corporation with more than 100 restaurants in China. By next year, they are going to have five restaurants in the US, with a flagship on the Las Vegas Strip.

Meizhou Dongpo opened its first US restaurant in Beverly Hills, California, in 2013, and kept its name exactly as it is in China, with the dishes selected from its menu in China. The chefs, though hired locally, were sent to China for months of training.

"We are trying to make authentic Chinese food for America," said Wang Xiaojing, the US general manager for Meizhou Dongpo.

In recent years, many Chinese companies have implemented a rapid "going out" strategy, buying properties around the world, merging with global companies and opening foreign subsidiaries. Restaurant brands are joining the movement.

"Fame has brought us pressure and responsibility, because Chinese restaurants who are considering opening locations in the US are all looking at us," said Wang. "If we make a success, they will take action. If we failed, they would be afraid of 'going out.' "

California is known for authentic, diverse Chinese food, driven by a large population of new Chinese immigrants. In Greater East Los Angeles area - Monterey Park, Arcadia, Roland Heights and other cities nearby, no matter which province of China you are from, you will be able to find your region's cuisine.

In place like Hollywood and Beverly Hills, however, residents don't see the variety of Chinese cuisine. There are Panda Express outlets in shopping centers, and take-out restaurants tucked in strip malls.

Meizhou found a rooftop dining deck at the Westfield Century City mall in Beverly Hills.

To maintain its food quality, the company brought a dozen of chefs from Beijing. They debated what dishes should be on the menu, spending hours analyzing if a dish would be liked by both Chinese and American diners.

"We decided that our rule was picking what Americans would like from our traditional Meizhou Dongpo dishes," Wang said. That way, they would not sacrifice authenticity in making dishes appealing to Americans.

Meizhou's opening created a buzz in the Chinese community. Chinese students and immigrants were excited to see a Chinese brand they could relate to coming to California. It also got the attention of American foodies.

"Popping fiery Szechuan dumplings on a sun-drenched patio at Westfield Century City is a new kind of mind blowing," Los Angeles magazine wrote.

Some were attracted by its authenticity.

"The times I've been by, at least half the patrons were Chinese, and I suspect they would not accept toned-down food," wrote a foodie on Chow.com.

The Peking duck seemed to have gotten the most love. "I have a new respect for duck meat design, as the chef displayed such patience as he skillfully assorted each piece of meat and crispy skin," wrote Ariel Zhu in LA Splash magazine.

"Americans like the duck the most," said Wang. "We are making it our signature."

Other popular items among American customers are familiar names such as kung pao chicken and shrimp and dan dan noodles. The Chinese customers usually come in for the dishes they cannot get elsewhere, like the pork hock.

Wang and his team have worked to please both their American and Chinese customers, because each group has its own preferences.

Their own entrees

"We realized Americans prefer that all the main dishes be served at the same time because everyone has their own entree," he said. "Chinese like the dishes to be served right when it's ready because they share the dishes. Our servers would put down a mark on the order letting the kitchen know whether the customers are Chinese or American so that we can accommodate better."

With revenue up 20 percent over last year, Meizhou Dongpo is more confident about what it is doing.

Instead of bringing shifts of chefs in from China, it has developed a system of sending Los Angeles local chefs to the Beijing headquarters, where they undergo professional training and a challenging test before graduating. The system raises the stability of chefs and food quality, Wang said.

Four new locations - three in the Greater Los Angeles Area and a flagship in Las Vegas - and a central kitchen in Baldwin Park are being developed at the same time, with an Arcadia location planned to open by the end of the year.

Authentic vs fusion

"For the 18 years the chef worked here, he barely had eaten at other restaurants. The servers had never been served properly before," Jonathan Ho said, shaking his head. Ho is the new owner of the restaurant Shanghai Cuisine in Manhattan's Chinatown.

Ho brought his chef to RedFarm, a modern Chinese restaurant owned by Ed Schoenfeld, a pioneer in the movement to bring authentic regional Chinese dishes to New York in the 1970s.

"For lots of Chinese chefs, the problem is not their crafts or experience, but their vision," said Ho. "Cooking is an art. A chef has to be aware of what other chefs are doing, while broadening his vision by listening to music, learning about art and more. Cooking is not a static action of turning the food in the wok."

Ho served the waiters at Shanghai Cuisine himself to show them how fine-dining restaurants treat their customers. With a soon-to-be updated interior and strict staff training, he wants to keep serving authentic Shanghai food and providing an upscale experience.

"Now diners have very high standards for restaurants. Every detail in my restaurant represents my attitude toward food," he said.

"Two ways we can redefine Chinese cuisine: First, stick with the most traditional and authentic Chinese food and make it better; second, innovation, play with it," Ho said. His theory matched with what the National Restaurant Association of America got through surveying 1,300 professional chefs and members of the American Culinary Federation.

On the 2015 Menu Trends to Watch list, "going global" stands with five others, like local sourcing and gourmet kids' dishes. And under the big umbrella of American restaurants going global, "micro-trending in this category is fusion cuisines, as well as authentic and regional, underscoring the breadth and depth of flavors being explored".

After taking over Shanghai Cuisine last October, Ho met a partner and decided they could open another Chinese restaurant to try out fusion cuisine. In March, Carma Asian Tapas opened its doors in New York.

With Carma, Ho is aiming for a "a playful place. A lab".

On the menu, there is the crispy wosum salad, made with lotus root and fresh shredded wosum - a vegetable most Americans had never tasted, and creative Peking duck tacos.

"Chinese chefs are becoming much less provincial, much more worldly. They are seeing other kinds of foods. Now you see Chinese people adding all kinds of food to their repertoire. They are feeling the influence of other cultures," said Schoenfeld, named "the walking encyclopedia of Chinese food" by eater.com.

"Low price, big portions and bad service are what Americans think of Chinese restaurants," Ho said. "We are challenging this impression."

Located in the hip West Village, Carma Asian Tapas has indoor seating, a full bar and a beautiful courtyard looking like a small siheyuan, or historical Chinese quadrangle.

On a Friday evening, the courtyard is packed. At one table, six ladies are having a girls' night out. In a combination of Cantonese and English, they spoke highly of the beef noodles.

Separated by blooming begonias, at the table next to the women, are a senior couple enjoying Xiao Long Bao and Peking duck tacos. House water is served in classic French restaurant glass bottles. Crystal ball string lights illuminate the yard when night falls, and the pathos plants stretch their short veins on the wall.

Chinatown changes

The night before the 2015 Met Gala themed China: Through the Looking Glass, Vogue magazine held a party at the Nom Wah Tea Parlor, the 90-year-old dim sum restaurant in Manhattan's Chinatown. Models and celebrities wrapped in silks and perfumes whirled on the padded stools with their Christian Louboutins dangling in the air as they indulged the aroma and steam of soup dumplings.

"I told Vogue from day one, 'No, I'm not interested. It doesn't fit my brand," said Wilson Tang, 36, the current owner of Nom Wah Tea Parlor. "They were trying to sell me the media exposure; I was being hardheaded about it. I'm more on brand with Bon Apptit.

"But they kept calling and calling. It was this constant, almost nagging, that I finally said, 'All right, all right, just do it and leave me alone.' "

"It ended up being very good," Tang said. "I think we've got a lot of exposure from it."

Manhattan Chinatown is seeing some gentrification but not as much as some New York neighborhoods, but real estate pressure is constant.

Many old timers are gradually moving out to Flushing, Queens, or Brooklyn, and more trendy bars and restaurants are wedging themselves in Chinatown.

"It's hard to see a place that I grew up in has such rapid change," said Tang, who was born and raised in Chinatown. "But it goes back to me saying, 'I need to make changes in order to survive.' "

When his uncle, Wally Tang, the previous owner of Nom Wah, decided to retire in 2010, Tang quit his finance job at ING and took over. To revive the family restaurant, he kept whatever he could to hold the place's historical appeal and updated some fixtures, like the kitchen equipment. But that's only the beginning of changes.

"I'm working on new menu items, how do we source better ingredients or more healthy items," said Tang.

"I'm having a lot of internal struggles with my chefs and my cooks," he said. "They are used to doing things a certain way. We can't change it overnight."

He's putting his vision into practice at a second location of the Nom Wah Tea Parlor, which opened earlier this year in Philadelphia's Chinatown.

"We are looking into methods of ornamentation," Tang said. "I was just back from Taiwan, looking at machinery that can make dim sum."

He engages with customers on social media, and he's working on starting a food-and-beverage-pairing program at the new shop. "It's either you improve, or you get left behind."

Affluence plays role

"Growing" is Schoenfeld's prediction of the future of Chinese cuisine, and he suggested two reasons for Chinese restaurants becoming increasingly upscale.

First is the change in food culture in China. As the economy grows, and Chinese people are becoming more affluent, they care more about what they are eating, said RedFarm owner Schoenfeld, and that will affect Chinese cuisine internationally.

"People have money. They spend on food. So, there is excitement in China about restaurants and food - traditional Chinese cooking and modern Chinese cooking. I think we are going to see more and more of these (upscale Chinese eateries)," he said.

Now good Chinese restaurants are paying their chefs well, said Schoenfeld, so the best chefs are rarely going abroad. But there is a growing number of rising local chefs working with Chinese food.

"Now it's becoming hip to be in the restaurant business, so there are many young talented chefs, like Jonathan Wu," said Schoenfeld, whereas in the past, being a chef was seen as an undereducated job, especially in families of Chinese descent.

Wu is the chef and partner of Fung Tu, a restaurant on the Lower East Side of New York, featuring creative Chinese-American food and a thoughtful beverage program.

By Chinese-American food, Wu doesn't mean sweet and sour chicken; he means food that he can relate to.

"Things that were important to me in term of the cuisine were originality and soulfulness," said Wu. "I would draw from food that I ate growing up, which were American Chinese dishes that my mother and relatives made."

Born in the Bronx, Wu was exposed to traditional Chinese ingredients from early on. There is a tree in his grandparents' yard in New Jersey.

"It's a Toona sinensis. In the spring, the leaves, when they first come out, they are very tender. It has this special flavor: it's garlicky, earthy, bitter," said Wu. "It's very Chinese in its palate. My grandma would harvest the leaves, chop them up, and fold them into scrambled eggs."

That's the inspiration for the dish "The Toon Cloud" at Fung Tu. With egg white-infused dashi, kombu, ginger and garlic, he makes a floating island. The cloud of eggs is served in the broth, and he drapes toon leaves over the top to highlight its flavor.

He also makes a dish called "smoked and fried dates". A relative from Shanghai told him about the food they ate as a child before the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), and Wu found the smoked and fried dates fascinating. He made the dish with American dates and stuffed the dates with duck instead of red bean paste, making them more savory.

For the owner Erica Chou and chef Doron Wong of Yunnan Kitchen, also on the Lower East Side, the goal is to show their interpretation of a Chinese regional cuisine - that of Yunnan province. The dishes are known for fresh ingredients and bold flavors.

"We ask ourselves, 'How would someone from Yunnan cook here?' " Chou said.

They look for the best ingredients of the season and start from there.

"It's Yunnan inspired; our interpretation of the cooking, creative process that's unique to us," Wong said.

While redefining Chinese cuisine in the US, these pioneers are up against American's deep-rooted perception of Chinese food: Cheap and large portions.

People are happy to pay $30 for pasta, but not Chinese noodles, said Tang, and they ask why the dim sums are $4, not $2. "Why can't we charge $30? The shrimp I buy is the same."

Chou has been asked why her dumplings are small compared with some sold in Chinatown.

"Dumplings are not supposed to be that big!" is her response.

Another challenge they are facing is Americans' eating habits. "They like bold flavors, like sweet, sour and spicy. They like fried food but not boiled," said Xiaojing Wang of Meizhou Dongpo. These tastes limit the restaurants when they pick menu items.

"We are trying to make changes," said Wu, but none of them is giving in.

"It's hard to do something you don't believe in," said Chou.

"There are still diners coming to Meizhou Dongpo and asking, "Do you have sweet and sour chicken?" said Wang.

They don't, and they are not going to carry it. That's the case with all the restaurants mentioned here, although Yunnan Kitchen gives a fortune cookie with the bill.

Contact the writer at hezijiang@chinadailyusa.com

|

|

|

Customers dine in the courtyard of Carma Asian Tapas in New York's Greenwich Village on July 10. Carma, which opened in March, serves fusion cuisine with dishes such as Peking tacos. hezi jiang / China Daily |

(China Daily 08/21/2015 page20)

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

A survival guide for singles on Chinese Valentine’s Day

A survival guide for singles on Chinese Valentine’s Day

Beijing police publishes cartoon images of residents who tip off police

Beijing police publishes cartoon images of residents who tip off police

Rare brown panda grows up in NW China

Rare brown panda grows up in NW China

Putin rides to bottom of Black Sea

Putin rides to bottom of Black Sea

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

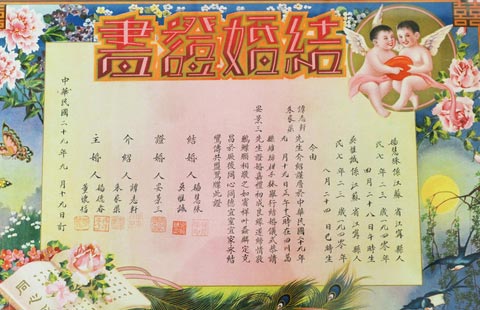

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Top 10 Android app stores in China

Top 10 Android app stores in China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chemical plants to be relocated in blast zone

Giant panda Mei Xiang at US zoo expected to give birth soon

S Korean president to participate in China's war anniversary

Thucydides Trap not relevant to today's Sino-US ties: Opinion

Fitch warns insured losses from Tianjin explosions could reach $1.5b

Conflicting reports on possible Abe trip

Hillary Clinton breaks with Obama on Arctic oil drilling

At UN, China backs regional peace efforts

US Weekly

|

|