The spy who saved the Soviets

Updated: 2015-08-26 07:45

By Zhao Xu(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Yan Baohang was one of China's most effective wartime intelligence agents and a trusted adviser to the Nationalist government, despite being a covert Communist. Today, this secretive man is remembered for an intervention that helped to bring Japan's occupation of China to an end. Zhao Xu reports.

As a child, Yan Mingguang regarded her father as a caring, uncomplicated man. "He would ride me to school on his bike and give me a goodbye kiss on the forehead when he left me at the dormitory. Once, I discovered a pair of nail scissors under my pillow. Dad had left them there because he wanted me to keep my fingernails short and clean," she said.

It was only when her father, Yan Baohang, died in 1968 that she discovered he had been a senior intelligence agent and had played a crucial role in alerting the Soviet Union to an impending invasion by the Third Reich in June 1941, just weeks before the Nazi troops were mobilized.

According to Guan Dingyi, secretary-general of the Yan Baohang Public Philanthropic Foundation in Shanghai, Yan acquired the information when he attended a banquet held by the Chinese Nationalist government to welcome a visiting Germany envoy.

"One got a deeper perspective on the intricate and ever-changing international relationships during the war, and understood what was really happening," Guan said.

"Turn the clock back to June 1941: Germany was flexing its military muscles and the United States had yet to become involved in the war. Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of China's Nationalists, was trying to maneuver through an increasingly complicated political landscape in the hope of making gains by forming the right alliances," he said.

According to Guan, Chiang had always been an admirer of the German military, and as headmaster of China's first military school, the Whampoa Military Academy, he purchased German-made weapons and invited several Germans to join the teaching staff.

By mid-1941, China was already four years into its war with Japan. Chiang saw the Germans as a potential mediating force, despite their having sided with the occupiers. "That was partly because Germany would want Japan to fight alongside her against the Russians," Guan said. "Gui Yongqing, China's military attache to Germany, was informed of the decision to attack the Soviet Union by his German hosts sometime in late May, and alerted the Nationalist government.

"Why would they attack? My guess is that Hitler was trying to simultaneously coax and coerce Chiang into cooperating with him. 'The Russians will soon be finished, so come and join us', is effectively what he was saying. Judging by Chiang's reaction, he was betting on the Germans," Guan said.

Yan was invited to the banquet because he was an adviser to the Nationalist government, but also a favorite of Chiang's wife, Soong May-ling. "My father said it was a very lively party and people were toasting as if celebrating a victory," Yan Mingguang, now 88, said.

"A Nationalist veteran approached my father and told him, quite casually, about the German plan. Deeply shocked, my father sought confirmation from a guest who was close to Chiang. The answer was affirmative."

Yan, who had secretly joined the Communist Party of China in 1937, wasted no time in reporting to his superiors in Yan'an, where the CPC was headquartered, and the news was passed on to Moscow.

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Eight days later, Stalin telegraphed Yan'an, to thank Yan "for his accurate information that prompted us to prepare for what's to come".

In 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, Yan was awarded a posthumous medal by a representative of then-Russian president Boris Yeltsin.

Early years

Born into a poor peasant family in Liaoning province in 1895, Yan earned the right to an education by standing outside the classroom window until a teacher took pity on him. In 1918, almost immediately after graduation from the local normal college, Yan opened a charity school for children from similar backgrounds to his own. He also became a member of the Young Men's Christian Association, where he met Zhang Xueliang, the son of Zhang Zuolin, who was known as the "Warlord of the Northeast".

"Founded in London in 1844, the YMCA was a global organization. It was introduced to China by an American Dane at the end of the 19th century. What it gave to Yan was not just religion, but a new way of living and a new way of thinking," Guan said.

From 1927 to 1929, Yan, sponsored by Zhang Xueliang, studied at the University of Edinburgh and toured Europe. By the time he returned to China, the political situation had changed dramatically. Zhang Zuolin had been killed by the Japanese, who saw him as an obstacle to their ambitions in China, and Zhang Xueliang had declared his allegiance to the Nationalist government.

"Yan came back to help Zhang and do his duty for the country," Guan said. "In around 1934, Zhang introduced Yan to Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Madame Soong. Yan impressed the couple, and was soon invited to take a government post.

The 'Xi'an incident'

On Dec 12, 1936, Zhang, who had become disenchanted with Chiang's military strategy, gave orders for his superior to be kidnapped and detained in Xi'an, Shaanxi province. "Before that, Chiang had deployed a sizable part of the Nationalist army to wipe out the Communists, whom he saw as a threat. By detaining Chiang, Zhang hoped to force Chiang to cooperate with the communists. After being held for several days, Chiang agreed to the formation of a united front against the Japanese, and was released.

"Upon Chiang's release, Zhang accompanied him on a flight from Xi'an to Nanjing, the Nationalist capital at the time, and was immediately placed under house arrest," Guan said.

According to a memoir Yan wrote in 1962, Madame Soong and her brother, T.V. Soong, a prominent politician, invited him to a meeting three days after Chiang's return. They asked Yan to negotiate the release of a number of top-level Nationalist officials and 50 US planes that were under the control of Zhang's generals in Xi'an, in exchange for Zhang's eventual freedom. Yan brokered the deal, and the men and the planes were soon back in Nanjing. Zhang, however, remained under house arrest for half a century, first on the mainland and then Taiwan.

"My father felt cheated. In the first few years after the 'Xi'an Incident', he tried everything to gain Zhang's freedom, but in vain," Yan Mingguang said.

Yan and Zhang met for the last time in February 1937, and in September Yan joined the CPC and was tasked with collecting intelligence.

By the summer of 1945, Japan was the last Axis country still fighting, despite its hopeless situation.

"But Japan still had one trump card - the 1.2-million-strong 'Kwantung Army', stationed in Northeastern China and seen as its mightiest force. It was at full strength and was expected to guard this last piece of ground 'for the Emperor', just in case the Japanese mainland fell," Guan said.

"The Americans hoped that the Soviets would attack and eliminate this giant army, but mindful of the powerful response it might unleash, Stalin hesitated. That's when Yan's crucial piece of information arrived," he added.

The Soviet Communist Party had asked the CPC for assistance, and Yan learned that Nationalist intelligence agents had detailed information about the army's deployment and defensive plans.

"An old friend of Yan's happened to be the brother-in-law of the Nationalist official in charge of the classified files. After much persuasion, the official agreed to 'lend' the files to Yan, for three days," Guan said. "It didn't take long for the information, which even included the names of low-level Japanese commanders, to reach the Soviets, who launched an attack on Aug 8, 1945. The move sealed Japan's fate, and the country surrendered on Aug 15.

"For my father, a Northeast native, that triumph, coming 14 years after my family left home during the Japanese invasion, was highly emotional," said Yan Mingfu, the younger brother of Yan Mingguang. "I remember riding on my father's shoulders during a demonstration against the invaders in Wuhan in 1938. I was about 7 at the time."

Life on the move

"The family was constantly on the move, but even though we were far from home, my parents provided a new home for those in need," Yan Mingguang said. "Our two-story house in Chongqing was always full of people. My brother and I quickly got used to being woken in the middle of the night to make room for a newcomer, who might be a disabled ex-soldier in need of food and shelter.

"One time, my mother opened the door to a man who begged for money to buy penicillin for his dying daughter, so she gave him her gold ring," she said. "And of course there were also fellow communists, my father's dearest comrades. They were hidden on the second floor or in the attic above. The Nationalists had strong suspicions that father was a communist, but thanks to his alertness and the relationships he'd cultivated with those in power, those suspicions never came to anything."

After WWII, a civil war erupted between the Communists and the Nationalists, and Yan was at last allowed to reveal his true political leanings. When the People's Republic of China was founded on Oct 1, 1949, he was appointed to a number of posts, including that of deputy chief of staff at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The bitter end

That prominence came to an abrupt end with the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). "My father was taken from home one night in November 1967. He died in prison on May 22, 1968 - although I only learned the actual date much later," said Yan Mingfu. "There's no name on my father's death certificate, just a serial number. My mother passed away in 1971, still not knowing what had happened to her husband."

In 1978, a year after the end of the "cultural revolution", Yan was rectified by the Chinese government.

"My father was finally laid to rest," said Yan Mingfu, who served as director of the United Front Work Department of the CPC Central Committee from 1983 to 1990, and worked to improve the tense relationship between the Chinese mainland and Taiwan.

In 1991, Yan Mingguang traveled to Hawaii to visit the 90-year-old Zhang Xueliang, who had been released from house arrest a year earlier.

"I told him what had happened to my father. Deeply saddened, Zhang, who had been the chief donor to the school my father founded in the northeast, proposed setting up a charity in my father's name. The Yan Baohang Public Philanthropic Foundation has existed for 24 years, and I am the honorary president and CEO," she said.

Reflecting on her father's life, Yan Mingguang said he had been a patriot first and foremost. "Throughout his life, my father searched for a truth that would bring prosperity to China. He fell under the influence of Christianity, which drew him close to Madame Soong, but he also looked into Buddhism and Taoism with great enthusiasm. Finally, Communism changed his life.

"People saw my father as a man of immense social grace, and for me his charm came from his passionate, sympathetic heart," she said.

"Back in 1967, sensing his imminent arrest, my father told me about his intelligence work during the war for the first time," she said. "He told me: 'Always remember, you father is a good man'."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Yan Baohang (first from right) accompanies then premier Zhou Enlai at a meeting with foreign guests in 1955. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

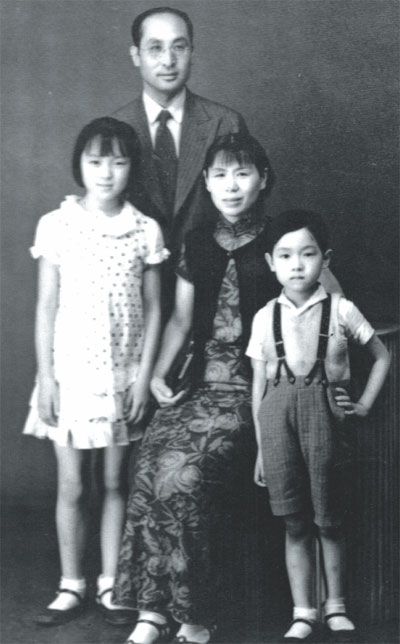

Yan Mingguang (left) and Yan Mingfu with their parents in Wuhan in 1938. |

|

Yan Mingguang (right) and her younger brother Yan Mingfu (left) visit Zhang Xueliang in Hawaii in 1991. |

|

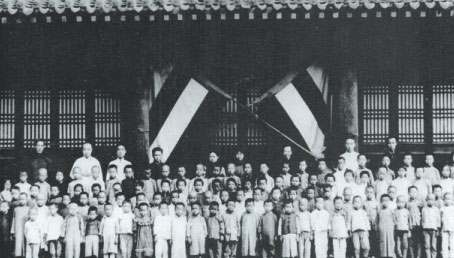

A 1921 photo of Yan Baohang (first from left, back row) with teachers and children at the charity school he founded in Liaoning province. |

(China Daily USA 08/26/2015 page6)

Bull crushes bear in stock market statue

Bull crushes bear in stock market statue

Top 10 emerging cities on the Chinese mainland

Top 10 emerging cities on the Chinese mainland

Jamaican Fraser-Pryce again becomes world champion

Jamaican Fraser-Pryce again becomes world champion

Glowing in the night

Glowing in the night

Mechanical horse dragon Long Ma performs in France

Mechanical horse dragon Long Ma performs in France

Giant panda Bao Bao celebrates two-year birthday

Giant panda Bao Bao celebrates two-year birthday

Across America over the week (Aug 14 - Aug 20)

Across America over the week (Aug 14 - Aug 20)

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Investors in for long haul amid selloff

30 heads of state to attend China's Victory Day celebrations

ROK, DPRK agree to defuse tension

Tsinghua University crowned 'wealthiest' Chinese school

China share plunge smacks world markets

China equities collapse sparks global markets sell-off

Targets set for regional integration

China advocates practical cooperation between LatAm, East Asia

US Weekly

|

|