Yesterday once more

Updated: 2016-05-31 07:51

By Raymond Zhou(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

A one-woman effort gets underway to re-create Beijing's glorious city wall and watchtowers that have long disappeared, writes Raymond Zhou.

When the sun was barely over the horizon on May 6, a crowd had already gathered outside the gate of the Red Sandalwood Museum on Beijing's east side. Commuters who were rushing downtown might be unaware, but they were passing witnesses to the unveiling of a project that can be traced back some 600 years.

Covering the front compound was a structure that is 18 meters by 17.2 meters and 5 meters tall. It was a replica of Beijing's Zhengyang Gate (Gate of the Righteous Sun). Some of the guests were standing on top of the wall, happily posing for photos.

|

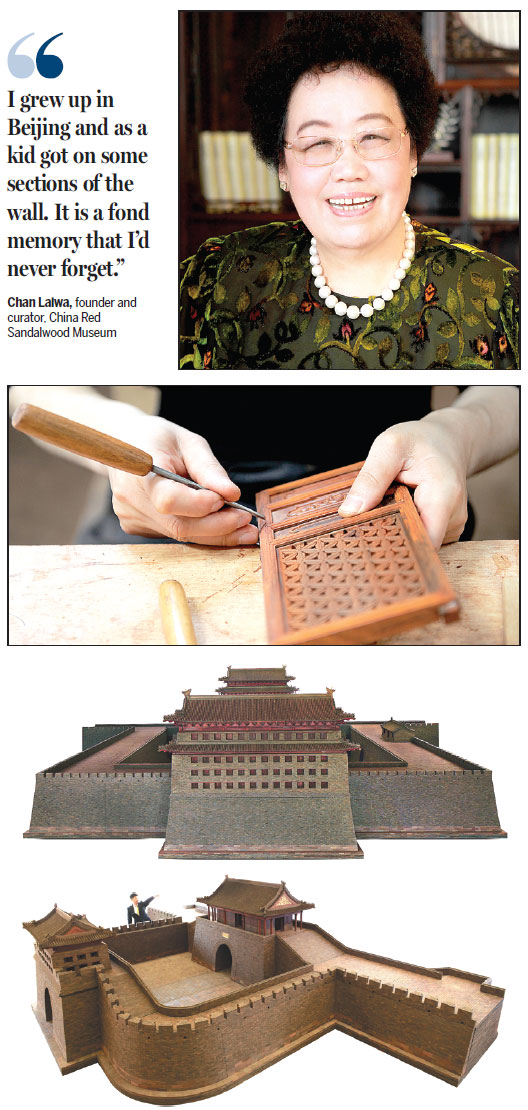

Chan Laiwa (right) visits the craftspeople working on a red sandalwood piece at a workshop of the Red Sandalwood Museum in Beijing. Photos Provided to China Daily |

It is one-tenth the size of the original structure. Instead of bricks and stones, the replicas are made of red sandalwood for the main buildings and Yinchen wood for the wall section, precious materials used mainly for collectible furniture and pricey artifacts.

As a matter of fact, the watchtower of Zhengyang Gate still stands to the south of Tian'anmen Square, but the surrounding structures, including an arrow tower and a barbican with two sluice gates, have long vanished. So, the replicas give a fuller picture than an actual tour of the original location.

It was not just one city gate that Chan Laiwa (Chen Lihua) and her red sandalwood museum had recreated, but all 16 of them that form both the inner circle and outer circle of the old Beijing wall. It is a project that took six years, a hundred top craftsmen and an untold amount of money.

"Of the 1.3 billion-plus in China's total population, probably less than 100 million have seen Beijing's city wall. We wanted to absorb and reflect their sense of awe and longing when they recall their experiences with the original structures. We wanted to capture that collective memory," says Chan, founder and curator of China Red Sandalwood Museum, and as ranked by Forbes in 2014, the 10th-richest mainland Chinese, the richest woman in China and one of only 19 self-made female billionaires in the world.

Fond memories

Beijing's fortifications were built in the 15th and 16th centuries. The inner city wall was 24 kilometers long and 15 meters high, with a thickness of 20 meters at ground level and 12 meters at the top. It had nine gates. The outer city walls had a perimeter of 28 km with seven gates. Stacked together, they form a "" shape on a standard map.

American architect Edmond Bacon once described the city wall as "man's greatest single architectural achievement on the face of the Earth". And Swedish scholar Osvald Siren wrote: "When you are standing by the gate's archway, you can feel the liveliness of the entire city, even the entire city's great expectations, all passing incessantly through these rather dark and narrow archways - the city's heartbeat, pumping life force to this incredibly complex organism called Beijing, giving it life, giving it rhythm."

Unfortunately, much of the city wall was dismantled in the 20th century, especially during the political turmoil of 1950s-70s. Only some isolated remnants are now visible.

"I grew up in Beijing and as a kid got on some sections of the wall. It is a fond memory that I'd never forget," recalls Chan, from an aristocratic family that had become impoverished after the downfall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Attending the unveiling ceremony, Shan Jixiang, curator of the Palace Museum (popularly known as the Forbidden City), gave a vivid summary of the city's history and the importance of the wall in public imagination: Human habitation of the place that would grow to be Beijing started as early as half a million years ago. A city came into shape 3,000 years ago and it became a capital city 800 years ago. Most people got to learn about its history through the Forbidden City and the old city wall.

"Today, the Forbidden City is still here but the wall with its gates and watchtowers is gone. It has yielded to the subway and a ring road. When I was a kid, we used to fly kites, catch dragonflies and skate along the wall. Most old Beijingers have tender and affectionate memories of the wall and now the replicas are a reminder of their cultural history. I believe it is a great way of making us remember who we are," Shan says.

Not just some replica

Since the replication is in miniature, it is reasonable that some may question its value.

Lyu Zhangshen, curator of the National Museum of China, who majored in architecture and has a special love for Beijing's old gates and watchtowers, says: "These are exquisite replicas of great architecture that can be called art."

Lyu compared the city wall model to one of the all-wood Buddha tower in Yingxian county, Shanxi province. The tower was built in 1056 and is now a world heritage site, but the model is from the 1950s. However, the model has been collected by the national museum.

"Madame Chan's models measure up to that standard. From the choice of material to the level of craftsmanship, they evoke the beauty of the original structures and also exhibit the finesse of the carvings themselves."

The national museum has already selected Anding Gate (Gate of Secured Peace) and watchtower and the Prayer Hall of the Temple of Heaven for display.

Liu Dake, a top scholar in ancient architecture and preservation, offered his in-depth analysis: "There are different ways of building models. The sceneries used for movies and television drama may look good, but they usually cannot stand closer inspection. Models for real estate projects or many museum displays are usually better crafted, but again they are not up to my standard."

When Liu was first consulted on this project, he asked that it possess the value absent from most models, that is, it should be backed up with scholarly research and achieve the potential to be collectibles with historical significance.

"Simply put, the models should have the function of a 3-D blueprint, with attention to all details," he says. "If you blow it up 10 times, it should be exactly like the original structures. Just look at the row of small animals on each eave, and you'll understand they deserve a whole book in explanation. Even those who have made a study of the subject may not be able to explain all the differences."

The replicas, he says, "are all accurate to every detail".

Yan Chongnian, a renowned historian specializing in Qing Dynasty study who was also consulted on the project, explained the choice of the scale.

"In the old days people did not use blueprints for architecture. The knowledge was handed down from master to apprentice. When Taihe Hall in the imperial palace was burned down in 1695, Liang Jiu, a carpenter who had pleaded with his master for the knowledge, used a scale model for reconstruction. That scale, 1:10, was adopted by Madame Chan for her red sandalwood replicas."

As much of the real structures were destroyed only in the last century, graphic records were in abundance. For those details that were undocumented, Liu says they could be easily inferred because the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing eras followed convoluted but strict protocols for the building of the capital city.

On top of that, everything was hand-crafted - and by those who have the best experience in the field. Chan herself was not bothered by the fine line between art and craft. For her, it is a labor of love - actually two passions fused into one, the love of rare wood and that of her home city.

Why red sandalwood?

Red sandalwood, known for its slow growth and rarity, is highly valued in China. Chan was heartbroken when she saw some of the furniture made from this lumber destroyed in political movements and has committed to restoring many of the royal pieces.

Early in her endeavor, she invited the Palace Museum's top three experts.

"They did not even look at me when they stepped into my workshop, let alone shake my hand," she recalls. But after they saw what she had done, they gave her a hug, a rare gesture in Chinese culture, and offered her a pass into the Forbidden City warehouses where she could make copies right from the originals.

Shan, curator of the Palace Museum, explains that although his world-renowned museum has the largest collection of furniture from the Ming and Qing dynasties, the 6,200 pieces are stored in 30 warehouses and rarely see the light of day or the appreciative eyes of visitors.

"We don't have that much space for display. Madame Chan's museum makes up for what we lack by showing these wonderful replicas to the public."

Shan has arranged for some of Chan's pieces to be showcased in exhibitions in the Palace Museum, where people could bid on them. "Our love for traditional culture and for fine furniture has grown as our lives become more and more affluent," he adds.

Chan's decision to create the city wall replicas with red sandalwood and Yinchen wood raised the stakes significantly, because these two timbers are rare and expensive. Red sandalwood tends to become hollow as it grows; and Yinchen wood, or a half-carbonized Salix mongolica wood buried underground for thousands of years, was chosen for its matching color with the wall bricks. "We bought lots of them, but could use only a small portion for carving," she says.

Yan the historian reveals that the cost for just one watchtower runs up to 100 million yuan ($15.4 million).

"Even in miniature, the project required unimaginable financial wherewithal," he says. "And enormous time, too."

The building of the actual architecture started from 1403 and took 20 years, and Madam Chan's lasted six years, he compared.

"I've known Madame Chan for 20 years. She dedicates herself to the preservation of traditional Chinese culture. Some of the rich love to flaunt their wealth through vulgar means, but she uses hers for this purpose. That is a great virtue," Yan comments.

Liu Dake, the expert on architecture, considers this project Chan's "greatest legacy".

"More than her red sandalwood furniture and her real estate assets, this one will be associated with her because future generations will be able to get a sense of the greatness of this old city," he says. "If you build one gate, it's just a gate; but if you build 16, you'll have mapped out a whole city."

Chan is negotiating with the government to build another museum, to be located in Beijing's eastern suburb of Tongzhou, a facility where each watchtower could be brought to view in its own hall. "I envision the busy shopping street outside Zhengyang Gate or even boats in the moat and river system. I want everyone to be proud of the city of Beijing," she says.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Top: A craftsman carves on a wooden structure of an old Beijing watchtower replica. Middle: The replica of Xizhi Gate and its watchtower. Bottom: The model of Guangqu Gate and its watchtower with a man standing next to it. |

(China Daily USA 05/31/2016 page7)

- Chinese G20 presidency 'ambitious' in seeking solutions for global growth: OECD official

- UNICEF alarmed at refugee, migrant deaths in Mediterranean

- 35% of northern and central Great Barrier Reef destroyed

- Vintage plane crashed in Hudson River during emergency landing

- 2,000 refugees relocated on first day of major police operation

- No sign of EgyptAir plane technical problems before takeoff

Robot-themed café debuts in East China's Shanghai

Robot-themed café debuts in East China's Shanghai

Cartoon: The birth and growth of China Daily

Cartoon: The birth and growth of China Daily

Students' special group photos to mark graduation

Students' special group photos to mark graduation

Memorial Day for remembering our beloved

Memorial Day for remembering our beloved

Disused buses turn into chic living spaces in North China

Disused buses turn into chic living spaces in North China

Graduation ceremony held in Confucius Temple

Graduation ceremony held in Confucius Temple

Wanda opens theme park to rival Disney

Wanda opens theme park to rival Disney

Fog turns Qingdao city into a fairyland

Fog turns Qingdao city into a fairyland

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Liang avoids jail in shooting death

China's finance minister addresses ratings downgrade

Duke alumni visit Chinese Embassy

Marriott unlikely to top Anbang offer for Starwood: Observers

Chinese biopharma debuts on Nasdaq

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

US Weekly

|

|