Chips off the old block

Updated: 2016-08-25 17:11

By Xing Yi(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

At times this craft has been close to extinction, but its stalwart defenders are unwilling to let it die

Jiang Xun calls them "the reflection of our civilization", an observation that would be on the money even if he were talking about the mobile devices of today that have become so much a part of our lives.

As it happens, Jiang is talking of the products of a much earlier medium of communication, etched woodblock printing. In sharp relief to the digital printing of today, in which speed of production is vaunted, the craftsmen of this early craft took great pride in the painstaking, time-consuming detail that went into turning out their exquisite wares.

In China 1,000 years ago it was the most common way of printing books, and countless craftsmen throughout the land carved out characters on wood blocks. Today those who practice it are few, a stubborn bunch who refuse to let the craft die.

A few blocks south of Tian'anmen Square in Beijing, in Yangmeizhu Alley, is Mofan bookstore, a redoubt of the craft that in addition to selling books has a workshop for Jiang, 46, and a handful of woodblock craftsmen, two full-time and three part-time, who continue to produce works of great beauty.

Jiang's remark about the characters and their reflecting civilization is all the more apt given that woodblock prints are a mirror image of the carving from which they are printed, and in their heyday they were the most common way, apart from the spoken word, of passing on knowledge from one generation to the next.

Woodblock printing was largely used to print Buddhist texts at first when the spread of Buddhism in China reached a peak during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). The oldest remaining woodblock-printed book is a copy of the Chinese version of the Diamond Sutra, which dates back to AD 868.

The book, now in the British Library in London, is in the form of a scroll, discovered in the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, Gansu province, in the early 20th century.

Jiang has collected more than 30,000 woodblocks, about one tenth of which date back to the Ming Dynasty (AD 1368-1644), which means he may have the largest woodblock collection of any individual in China.

Between 2009 and 2012 a few of his prints were on display in a branch of the National Library in Wenjin Street, Beijing, the only one of its kind in the capital.

"In a sense, woodblocks are progenitors of the book," says Jiang, who is also renowned in China as a book designer. "All my works are associated with books."

In late 2014 when the Nobel Museum in Stockholm invited him to design a book for the 2012 Nobel Prize for Literature laureate Mo Yan to present in its exhibition, Jiang decided there was no better way of interpreting Mo than through a traditional Chinese thread-bound book printed using woodblock.

The book is a short story called Gale that Mo chose from his early works that has about 4,000 characters, and Jiang decided to use a font from Caochuang Yunyu, a poetry anthology by the poet Zhou Min in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), for the book.

Jiang says it took him three months to choose the matching characters from Zhou's poems and piece them together for Mo's short story.

Then he needed to prepare the woodblocks for printing, a process in which wood is carved away, leaving the characters to stand out as a relief pattern for inking and printing.

"The process is difficult because it is such a rare font," says Zhao Yishen, 30, who carved pages one to six of Mo's book. "It's like calligraphy, with many elements of handwriting."

Zhao says that with most printing fonts he can carve about 30 or 40 characters a day, but with the font for the Mo book the number was halved.

"As carvers we aimed to make the characters look as natural as the original writing, not too stiff."

With five other carvers, Zhao worked on the book each day for three months from 8 am to 6 pm.

"It needed the utmost concentration. I took breaks whenever my eyes got sore, and whenever I began to lose focus I stopped to avoid making mistakes."

The work lasted until March last year, after which 274 copies of the book were printed, and they went on display in Stockholm in mid April.

"It's all handmade, from carving to printing to binding," Jiang says. "When the book and the woodblocks went on display in Stockholm, those who saw them were in awe because in the West there is no tradition of thread-bound books."

Jiang kept just one woodblock piece from the Mo production - a piece produced twice in error.

Printing technology

When Zhao was studying at Beijing Jiaotong University for a law degree, which he gained in 2010, he became engrossed by ancient classic texts in the traditional thread-bound form in library.

"Different books have different fonts depending on when they were published," he says.

Apart from the literary content, the beauty of the characters thrills Zhao.

"It's simply beautiful."

These days only around five publishers in China produce books through traditional woodblock printing, and the year Zhao graduated he visited one of them, Guangling Ancient Books Printing House in Yangzhou, Jiangsu province.

"It was the first time I had really seen what those woodblocks were. It seemed like an impossible mission for me to make one, but I wanted to try."

Being an intern

He decided to stay as an intern, and after a year's internship in the printing house he became a student of Chen Yishi, one of the few people who holds state accreditation as a master of the engraved block printing technique.

Chen has a family tradition of engraved printing. His grandfather was a woodblock printer in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and opened a family workshop in the town of Hangji in Jiangsu, once a book printing center.

However, during World War II many woodblock printing workshops closed, including Chen's, and later, during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), a call for traditions to be swept away all but put paid to the ancient craft.

Chen says his fathers words "We must pass on the craft" made a great impression on him, so he went back to the trade in the 1980s, and since retiring from Guangling Ancient Books Printing House in 2007 he has continued to train apprentices.

"Over the years I have had about 100 students, but only about a quarter of them are still doing this work. It doesn't pay well, and there are not enough commissions, so they work on and off for some time and eventually do something else."

But Chen says that since the technique was included in UNESCO's human intangible cultural heritage representative list in 2009, things have improved. Seven students study with him, some sent by publishers such as Guangling Ancient Books Printing House, and some, like Zhao, coming independently.

"I aim to teach them everything I know," Chen says. "Only about 20 people in Yangzhou have mastered this skill, so if I don't teach them I am afraid the skill may be lost."

xingyi@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Above: Woodblock carver scrapes off parts of the block with various cutting tools. Left: Notebooks designed by Mofan bookstore. Right: Book printed with woodblock. Photos By Fong Yongbin / China Daily |

|

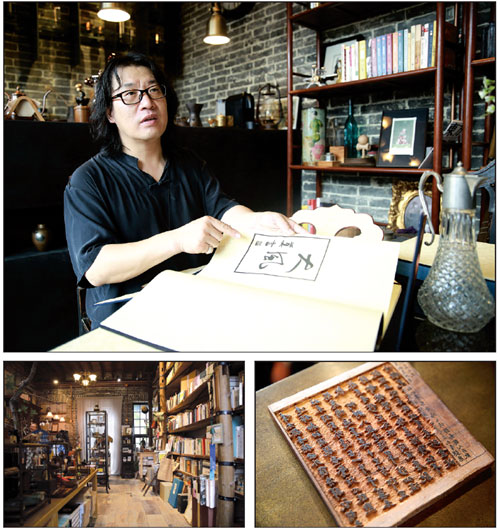

Clockwise from top: Jiang Xun with his design of Mo Yan's book Gale; which took three months of highly concentrated work to prepare; a view of Mofan bookstore. Photos By Fong Yongbin / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 08/25/2016 page10)

- Talks with Manila at early date expected

- Respect, protect nature during development: Xi

- School to compensate parents of students studying in US

- Gobi has been found! Marathon-running stray dog reunites with owner

- Six Chinese youths make MIT's innovators of the year list

- Whale shark found dead in

East China

- Prince William and Kate visit charity orgarnization in Luton

- China welcomes Japan to play constructive role in G20 summit

- Expert: G20 ushers in collective leadership

- Turkey to provide support for anti-IS operation in Jarablus

- China, Japan, S. Korea should work to make differences controllable

- Several killed after strong quake strikes Italy, topples buildings

Top 5 fitness bands in customer satisfaction

Top 5 fitness bands in customer satisfaction

Orangutan goes shopping in Southwest China

Orangutan goes shopping in Southwest China

Prince William and Kate visit charity orgarnization

Prince William and Kate visit charity orgarnization

London Zoo's animals have annual weigh in

London Zoo's animals have annual weigh in

Ukraine celebrates Independence Day

Ukraine celebrates Independence Day

Top 5 smartwatches in customer satisfaction

Top 5 smartwatches in customer satisfaction

Woman creates silk Chinese cabbage

Woman creates silk Chinese cabbage

Panda family celebrate birthday in Malaysia

Panda family celebrate birthday in Malaysia

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Trump outlines anti-terror plan, proposing extreme vetting for immigrants

Phelps puts spotlight on cupping

US launches airstrikes against IS targets in Libya's Sirte

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

Abe's blame game reveals his policies failing to get results

Ending wildlife trafficking must be policy priority in Asia

Effects of supply-side reform take time to be seen

US Weekly

|

|