Society

Climbing the art of survival

Updated: 2011-05-10 08:00

By Feng Xin (China Daily)

|

Students from Tibet Mountaineering School climb a snow-capped mountain in the Tibet autonomous region. Provided to China Daily |

Tibetan youngsters are taking on tasks that were once dominated by Nepal's Sherpas, in the high mountains of the Himalayas, thanks to a training school established in 1999. Feng Xin reports.

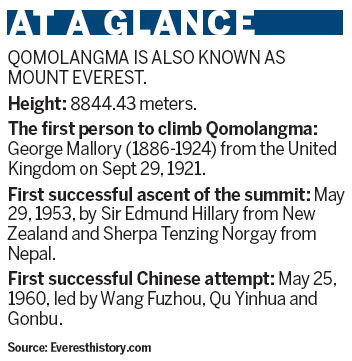

Tsering Samdrup has been busy on the phone since mid-March. As he enters his busiest time of the year, so does Qomolangma, the tallest mountain on Earth. The peak, also known as Mount Everest, welcomes 400 to 500 climbers worldwide each spring, according to the Tibet Mountaineering Association. As an accomplished mountaineer and high-altitude videographer, Tsering is organizing another adventure for a group of climbers in May, the best season to challenge the summit. "The weather, temperature and thickness of the ice all make for a perfect climbing season," says Tsering, who started his professional climbing career in 1999 when he joined the first class of students at Tibet Mountaineering School, established the same year.

The school, one of only two permanent mountaineering schools in the world (the other being France's l'Ecole Nationale de Ski et D'alpinisme), provides free professional training and boarding for scores of 16- to 18-year-old Tibetans, says Nima Tsering, founder and principal of the school.

"I have three strict rules for all students," he says. "No alcohol, no smoking and no girlfriends."

This is necessary because of the extreme danger of mountaineering, he explains.

Graduates of the school have scaled Qomolangma more than 130 times as mountain guides, assistants, videographers and chefs accompanying various domestic and international expeditions since 1999.

Before the school's opening, Sherpas - an ethnic group inhabiting Nepal's most mountainous regions - typically took these occupations, Nima says.

He served as Qomolangma's liaison and translator on the Chinese side for many years, before starting his school. He saw that while the Sherpas had dominated the mountaineering service for almost a century, many Tibetans lived in extreme poverty along the Himalayas.

"I felt we desperately needed to train our own people," Nima says. "If I could establish a school, I knew I could secure jobs for these youngsters."

But he had no money.

Thanks to the many good friends he had made over the years, he received donations from an outdoor sports gear company to start the school.

He was also able to invite professional coaches from France for the first few winters.

"I can't remember all the difficulties I had to face along the way," he says. "The 12 years have not been easy."

The Tibet Mountaineering School currently has about 50 students and 30 teachers. After training seven batches of students, the school now has its own independent team of instructors, says its principal.

Apart from inviting foreign professionals, two students are selected to go to the Alps in France every summer for training. Tsering was one of the first such students.

|

Like him, the school's students are recruited mainly from Qomolangma's core areas, including Dinggye, Nyalam, Dingri and Gyirong counties in Tibet's Xigaze prefecture. People born in these high-altitude areas are more capable of heavy physical work in conditions where the air is very thin, with little oxygen, Nima says. The students' family backgrounds are also conducive to motivating them as many of their fathers and grandfathers once worked as porters alongside the Sherpas.

In order to be admitted to the school, applicants need to pass both a physical and a literacy test.

Phurbu Dhondrup, a member of the first class and now a coach at the school, recalls how he was asked to run 3 km when the recruitment team went to his hometown 12 years ago. Over the years, he has climbed Qomolangma four times - all without carrying oxygen.

Phurbu still remembers his excitement when he first reached the summit in May 2003, the 50th anniversary of the first successful attempt to reach Qomolangma's summit. The climb was organized to commemorate New Zealand mountaineer Edmund Hillary (1919-2008) and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay (1914-1986)'s climb in May 1953.

The 2003 expedition also brought the Tibet Mountaineering School to international attention. Nima and five other members of the school reached the summit while assisting China Central Television's live broadcast of the climb.

The school was again in the spotlight in May 2008, when more than 70 members of the school took part in the Beijing Olympic Torch Relay Expedition with Nima bearing the torch.

"High altitude service is no longer dominated by the Nepalese," Nima says. "I think we've changed the landscape of world mountaineering."

According to data compiled by Exploresweb.com, between 1922 and 2006, 11,000 attempts were made to scale Qomolangma but only a third were successful. Two in every 100 climbers died on the mountain, and some died after reaching the summit.

A 2007 study published by the Himalaya Database shows that falls, high altitude sickness and hypothermia claimed the most lives on the mountain.

"Climbing is the art of survival," says Li Lan, a professional climber and teacher at the mountaineering school.

Li began climbing in 1996 as an advertising student at Peking University. An adventure seeker, she joined the university's student-run mountaineering society.

|

As an amateur climber, she was witness to two accidents that killed her teammates in 1999 and 2002. Although haunted by those horrifying incidents, Li was unable to stop climbing.

"When you are climbing," Li says, "you feel a sense of danger that constantly stimulates you. You mobilize your whole body. You are always in an extremely excitable mental state, ready to react to dangers at any moment. All your energy, both physical and psychological, is focused in one direction."

Li's passion for climbing finally compelled her to quit her job as a white-collar worker and become a professional climber. She now teaches mountaineering theory at the school.

Students study a variety of subjects in the morning, including Chinese, Tibetan, English and Tibetan history, culture and geography, besides mountaineering theory. Afternoons are devoted to the outdoors and include rock climbing, knowledge of operating equipment, and physical training. Students also get to do two real mountain climbs every spring and fall.

Although all the subjects are mandatory, students go on to specialize in one of the four fields provided by the school curriculum - mountain guidance, assistance, videography and cooking, Nima, the principal, says.

Of these specialties, mountain guidance demands the most expertise and experience - to organize a team, select base camps, track weather conditions and decide expedition routes. It takes eight to 10 years of training and practice for a student to become a qualified mountain guide, Nima says. Working as a mountaineering assistant for many years is a prerequisite for becoming a guide, he adds.

Despite the rigor, almost all the students dream of becoming a mountain guide.

One of the walls of their classroom is covered with their writings under the heading, "Why I Climb".

"I didn't know what climbing was," writes a student, Wanglha. "I just saw people from the mountaineering school all wearing nice clothes, so I wanted to become a student, as well. But now I know what climbing is. It's dangerous but also joyful."

Another, Dawa Sambu, writes: "First of all, our school doesn't charge tuition fees. And secondly, I have loved climbing since I was a child."

Back on the training field, the students are running, lifting weights and playing soccer. Sitting in a corner on the artificial grass Phurbu, their coach, watches them.

"Climbing is a sport without spectators or applause. But as long as you know why you have chosen it," he says, "you will enjoy it."

Meanwhile, striking a note of caution, Nima says: "Tibet is the world's water tank."

If the mountaineering industry develops too fast, he says, it will lead to two serious consequences: "First, there will be many accidents and deaths. And second, Tibet's glaciers will melt more quickly than usual."

In the past, he points out, many Tibetan porters assisting early climbers did not pay much attention to the environment. But now students of the mountaineering school have to study environment protection as part of their curriculum.

"We teach our students that the water they drink comes from the mountains they climb," Nima says. "If they pollute the glaciers, people who live downstream will have to drink dirty water. They have to protect their own home and influence their children. That's the mountain culture.

"We have to climb slowly. We need to climb step by step."

Specials

Sino-US Dialogue

China and the US hold the third round of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue from May 9-10 in Washington.

V-Day parade

A military parade marking the 66th anniversary of the Soviet victory over Nazi.

Revolutionary marriage

A newlywed couple sings revolutionary songs during their marriage.