Society

In Haiti, classes come with a peek at the lush life

Updated: 2011-05-22 08:29

By Sarah Maslin Nir (New York Times)

|

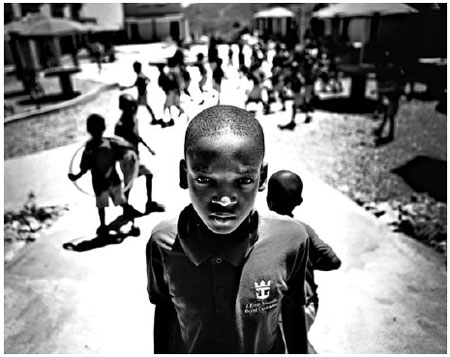

About 200 Haitians, including Rodman Decius, attend a school built by Royal Caribbean Cruises. Piotr Redlinski for The New York Times |

LABADIE, Haiti - On a jungle-covered hill, about 25 Creole-speaking kindergartners chanted numbers inside a gleaming classroom. Past noon, they spilled into the courtyard to dash across the gravel in a blur of blue and cream uniforms, each one embroidered with an anchor and the school's unusual name: "Ecole Nouvelle Royal Caribbean," or the New Royal Caribbean School.

For years, Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd., the cruise line corporation based in Miami, has run a private resort on a sandy promontory nearby. But in the wake of the January 2010 earthquake that devastated the capital, the cruise line evoked harsh criticism when it resumed docking pleasure ships at the resort just six days after the quake killed as many as 300,000 people. Then the company opened the cheery citrus-colored school complex in October.

"I'm not saying we do this because it's a completely altruistic motivation," said John Weis, an associate vice president, "but I think that our management feels that we have a responsibility to make a difference down here."

While residents seem to agree that the school is a boon to the community, the praise is tempered by doubts.

"Royal promised a school that was to be different from other ones in Haiti," said Paul Herns, 29, who teaches fifth grade. "Where children are fed and have access to sporting activities and taught some English skills to speak to foreigners; where they can surf the Web. These services have not yet been provided."

He echoed a common sentiment: gratitude mixed with the feeling that the company, which had revenues of $6.8 billion last year, could do a lot better.

The school itself is stunning and serene. It is certainly a far cry from local schools like L'Ecole Nationale Mixte in neighboring Fort Bourgeois, where splintering desks teeter on dirt floors. But because of a decision to build on hilltop land controlled by the cruise line, it is also remote.

Many students commute piled into the backs of pickup trucks, or "tap-taps," the jalopies that serve as local taxis, which the company says it subsidizes. Some students like Rodman Decius, 13, say they cannot always afford even subsidized transport. Rodman has an hourlong commute marching home through jungle paths, at points clambering along a cliff face with a sheer drop to the sea.

Eddy Hippolyte, a taxi driver, said some people feel the company should have improved existing schools. But others, like Jacques Renelle, 37, who teaches kindergarten, are more supportive. "The overall good outweighs these irregularities," she said.

Mr. Weis is rankled by what he sees as the "give an inch take a mile" attitude he feels the company's charity work engenders. "We have a responsibility to the community that we're in," he says. "But it's not unlimited."

For students, the shining school is not the only oasis they know. The cruise's resort lies just down the road, cut off by a fence. "I wish I could play there," Rodman says, "But I don't have any money."

The New York Times

Specials

Suzhou: Heaven on Earth

Time-tested adages sing praises of Suzhou, and Michael Paul Franklin finds it's not hard to understand why on a recent visit.

The sky's the limit

Chinese airline companies are increasingly recruiting pilots and flight attendants as the industry experiences rapid expansion.

Diving into history

China's richest cultural heritage may lie in the deep, like exhibits in a giant underwater museum.