Society

I.B.M.'s longevity lessons: core resources, refocused

Updated: 2011-06-26 07:37

By Steve Lohr (New York Times)

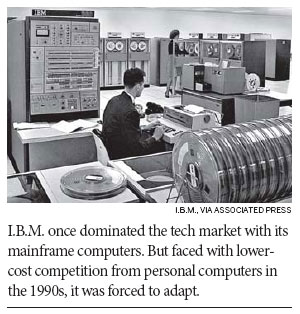

At 100, I.B.M. looks remarkably spry. Consumer technologies get all the attention these days, but I.B.M. has thrived by selling to corporations and governments. Profits are strong, its portfolio of products and services looks robust, its shares are near a record high. Its stock-market value passed Google's this year. Yet, in the early 1990s, I.B.M.'s survival was at stake. It nearly ran out of money. Its mainframe business was reeling under pressure from the lower-cost technology of personal computing.

"I.B.M. faced the challenge that all great companies do sooner or later - they dominate, they lose it, and then they recreate themselves or not," says George F. Colony, the chief executive of Forrester Research, a technology and market research company.

I.B.M. moved beyond the mainframe and built a business increasingly based on software and services. And the company holds lessons for others.

Evolving beyond past success is a daunting task for all companies. But that problem is magnified in the technology arena, where companies can quickly rise to rule a market, until a technology shift opens the door to a new generation of corporate dynamos.

That is the test facing Microsoft, Google and Apple. So, what broader insights are to be drawn from the I.B.M. experience?

One central message, according to industry experts: Don't walk away from your past. Build on it. The crucial building blocks, they say, are skills, technology and marketing assets that can be transferred or modified to pursue new opportunities. Those are a company's core assets, they say, far more so than any product or service.

I.B.M.'s prime assets included strong, long-term customer relationships, deep scientific and research capabilities, and an unmatched breadth of technical skills in hardware, software and services.

It is the technology surrounding the mainframe that pays off for I.B.M. today. Mainframe hardware alone accounts for less than 4 percent of its revenue. But when the software, storage and services contracts linked to mainframe computers are included, the figure rises to 25 percent - and as much as 45 percent of operating profit, estimates A.M. Sacconaghi, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Company, a global wealth management firm.

I.B.M. has refocused its research labs and sales force on services and software. From running smart-grid projects for utilities to traffic-management systems for cities, I.B.M. acts as a general contractor whose expertise spans research, software, hardware and services. These projects build on its legacy of broad technical skills and deep knowledge in fields like energy, transportation and health care.

Unlike I.B.M. in the early 1990s, Microsoft is not a company in crisis. It is growing and is immensely profitable. It has nurtured new businesses beyond its lucrative stronghold in personal computer software: the Windows operating system and its Office programs.

Today, Microsoft's server software division is comfortably profitable, with $16billion a year in revenue.

Its other sizable business is its Xbox video-game console, software and online gaming franchise. That division is an $8billion-a-year business.

But the long-term problem for Microsoft is that more than 80 percent of its operating profit still comes from its PC software franchise, which has kept the company's stock price stagnant for years. And the company lags in fast-growing new markets in search and online advertising, as well as smartphone and tablet software. Some big investors are uneasy - and one, David Einhorn, the hedge fund manager, in May publicly called for Microsoft's chief executive to be replaced.

Microsoft has deep technical and research expertise. Kinect, its add-on device to the Xbox gaming console, suggests promise. It recognizes faces, gestures and voice commands.

Kinect (at $150) is for gaming, yet personal computers that can see you, hear you and respond would be a breakthrough, bringing artificial intelligence into the mainstream.

Google has the purest engineering culture among the major technology firms. And the assets most prized at the company are brains and data.

"Google is all about information - searching, discovering and sharing information more intelligently," says Peter Sondergaard, senior vice president for research at Gartner, a technology research company.

Google sees itself as an artificial-intelligence factory. Its programmers mine vast troves of Web data to deliver smarter search results and more finely directed ads. Its offerings beyond search all scoop up more data and afford potential opportunities for serving up more ads. They include online e-mail, calendars, maps, shopping, word processing and spreadsheets, as well as videos on its YouTube service and photographs on Picasa.

I.B.M.'s story holds a cautionary lesson: the danger of delay. David B. Yoffie of Harvard Business School recalls that in 1990, I.B.M. executives spoke of the need to wean the company from its dependence on mainframes and to shift to software and services.

I.B.M., he notes, didn't pursue that strategy until after the company was in peril. "It's really hard," he said, "to move a company when it's doing well and not facing a crisis."

The New York Times

Specials

Premier Wen's European Visit

Premier Wen visits Hungary, Britain and Germany June 24-28.

My China story

Foreign readers are invited to share your China stories.

Singing up a revolution

Welshman makes a good living with songs that recall the fervor of China's New Beginning.