Health

Breast-fed is best fed

Updated: 2011-08-10 07:54

By Yu Fei (China Daily)

|

Guo Fengxian, a young mother from Yangjiu village in Wuding county, Yunnan province, feeds her baby food supplements. Photos by Qin Qing / Xinhua |

|

Zhang Xianli, a mother in Yangjiu village, Yunnan province, breastfeeds her baby. |

Fewer than one in three Chinese moms put their babies exclusively on breastmilk for the first six months of life, even though it's the best source of nutrition for infants. Yu Fei of China Features reports.

Hearing her toddler wail makes Zhang Shuyi feel nervous. She continues to breastfeed her 2-year-old, supplementing the toddler's diet with solid foods, but worries he may not be getting enough milk and is crying from hunger.

Zhang, 35, is a doctor at the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing, and a believer in what is known as "exclusive breastfeeding" - defined internationally as putting an infant on just breast milk for the first six months of life and supplementing the child's diet with solid foods for the next two years.

Although her son looks healthy, he is much thinner than other children his age, much to the dismay of her parents and in-laws.

For older Chinese, fat babies are healthy babies, and Zhang's parents have urged her to switch to formula milk.

Since China adopted the global definition of "exclusive breastfeeding" in 2007, there are no reliable statistics on it before that year.

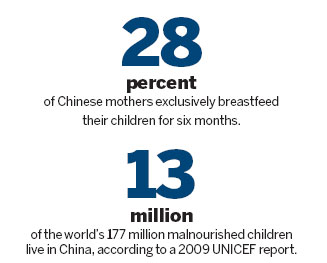

David Hipgrave, chief of health and nutrition for UNICEF China, says, "According to the most recent national statistics from the 2008 national health service survey, the rate of exclusive breast-feeding is 28 percent for six months.

"This is a bit higher than we expected but still rather low."

Many studies have shown that breast milk is the most hygienic source of nutrition for infants during the first six months of life. Even when solid foods are started, breastfeeding should continue for up to two years since it is an important source of nutrition, experts say.

There is evidence that breastfeeding protects infants against sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), allergies, acute respiratory infections and ear infections. A WHO-led global study shows that adults who were breastfed as infants had lower blood pressure and cholesterol, as well as a lower prevalence of obesity and diabetes.

"Although I know a lot about breastfeeding, I still worry that my milk is not enough for my child," Zhang says.

Her husband, Liu Huan says: "I know from the child-rearing training sessions that I attended before my son was born that breast milk is the best for our child. I always encourage my wife to breastfeed our baby, but sometimes, it's very hard for her."

Zhang says that the first month after her baby was born, as well as the time she returned to work after exhausting her maternity leave, were the hardest.

The first month she worried she wasn't feeding him enough. Resuming work left her feeling very tired, and this affected her ability to produce milk.

Zhang continued to breastfeed her baby after he reached his first birthday, a time when most Chinese mothers wean their children. "Many people have criticized me. But I remember that once this old woman saw me feeding my son and said, 'What a fortunate child'. I felt so happy to hear that. If only more people could give us such encouragement," she says.

An Jiangqun, 32, was still receiving calls from work as she was making her way to the hospital delivery room. She couldn't produce any milk right after giving birth and her daughter, now 7 months, had to be put on formula straight away.

However, An kept trying and has breastfed her child every day since. She even hired a nurse to give her massages to help her produce more milk.

When An resumed work, she found she had little time to continue breastfeeding. "I considered switching to formula, but I've managed to persist," she says.

She relocated to a new home closer to her office and purchased an electric bicycle, allowing her to make quick trips during her lunch break to breastfeed her baby. On days when she can't make it home, she carries a breast pump and an icebox to collect and store the milk for her baby to drink later. Her goal is to keep breastfeeding through her child's first year.

"Although my daughter is thinner than other babies her age, she could stand up on her own much earlier than others. She plays by herself and doesn't cry much," An says.

She often browses online parenting forums, encouraging other parents to breastfeed and even swaps tips with other mothers.

Hipgrave says that breastfeeding is not always easy for women in China. They often regard breastfeeding as a very private activity, finding it difficult to breastfeed in public places, most of which have no private rooms.

He also says the pervasive presence of advertisements for baby formula and promotions of breast milk substitutes have shaken the confidence of many young mothers to breastfeed.

An says she doesn't know how the milk powder companies got access to her telephone number. They often call her to promote their products. During public parent-child activities and holidays, the companies are quick to make their presence known, setting up booths and handing out free gifts.

Although China enacted a law to prohibit the advertisement and promotion of breast milk substitutes in 1995, its enforcement lacks teeth.

According to an investigation conducted by the China Consumers Association in 15 cities, including Beijing, Chongqing municipality and Liaoning's provincial capital Shenyang, formula manufacturers invariably target hospitals, malls and supermarkets to market their products.

Experts say formula milk powder makes children more prone to infections, asthma, meningitis, obesity and diabetes. Low-quality milk powder and formula substitutes are often marketed in poor rural areas, where many parents have been forced to leave their children in the care of grandparents while they work in the cities.

Although rates of breastfeeding in rural areas is much higher than in the cities, people in rural areas have many misunderstandings about breastfeeding.

Ye Yan, a village doctor in Baizi, Yunnan province, says more than 90 percent of the women in the village breastfeed their children until they are 1 year old.

But at the same time, she says, mothers are encouraged to add supplementary foods as early as the fourth month.

Malnutrition is common among infants older than six months in these remote, poor regions, as a result of the improper introduction of supplementary foods.

According to a 2009 UNICEF report on nutrition, China is home to 13 million of the world's 177 million malnourished children. Although these numbers have declined, China has more of them than any country in the world, except India. Chen Chunming, an expert with the China Disease Prevention and Control Center, says many children younger than age 2 suffer from anemia because traditional Chinese diets lack fresh meat, which leads to iron deficiencies.

The rate of anemia among urban infants is more than 20 percent, with the figure going up for rural infants, Chen says.

UNICEF is cooperating with the Chinese government to provide food supplements to address nutritional problems. Families in 550 rural counties will be provided with free daily supplements, which contain a mixture of nine vitamins and minerals in a soybean-based powder. Counties in the provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi and Sichuan have already seen a 30 percent reduction in new anemia cases since the introduction of the supplements in 2009.

Specials

Star journalist leaves legacy

Li Xing, China Daily's assistant editor-in-chief and veteran columnist, died of a cerebral hemorrhage on Aug 7 in Washington DC, US.

Beer we go

Early numbers not so robust for Beijing's first international beer festival

Lifting the veil

Beijing's Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City, is steeped in history, dreams and tears, which are perfectly reflected in design.