Focus

Age-old problem looms for families

By Duan Yan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-14 07:54

|

Large Medium Small |

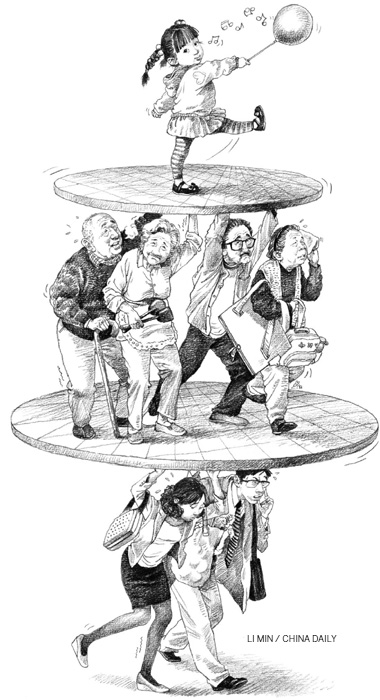

The 4-2-1 structure poses challenges to providing care for the elderly. Duan Yan in Beijing reports.

After another national holiday spent squeezing onto cramped trains to visit relatives, Li Wenbo and his wife Jia Xuan had the luxury of leaving their 2-year-old daughter with Li's parents this week.

Like many modern couples, being able to get some respite from the daily pressures of parenthood is the best thing about the so-called 4-2-1 family.

The reverse-pyramid dynamic - four grandparents, two parents and one child - is rapidly becoming the new norm in Chinese cities, largely as a result of three decades of the country's family planning policy, which resulted in most couples having only one child.

However, although the first generation born after the policy is reaping the benefits (read: six people to care for one child), sociologists warn that in 10 to 15 years the burden of providing elderly care could be too much for smaller families.

"Even though elders in these 4-2-1 families are in good health now and can help with chores and child care, the problem in the foreseeable future will be the lack of manpower to take care of them," said Yuan Xin, a professor at Nankai University's population and development research institute.

Traditionally, Chinese people are expected to care for their parents in later life. Yet, the fact families are shrinking and people are living longer means younger generations and China's elderly care services face immense pressure in coming years.

China had 100 million one-child families in 2000, according to a research by Yuan. He estimates that by the end of this year, as many as 18 million married couples will include two people born to only-child families.

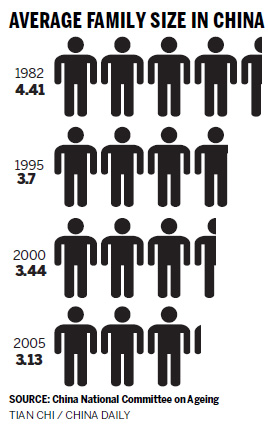

Results of a 2005 government-backed study of 1 percent of the population also showed the average family size had fallen to 3.13 people (2.97 in urban areas), compared to 4.41 in 1982.

And some 4-2-1 families are already experiencing the problem of elderly healthcare.

When Li Jinya's father was severely injured in a car accident last year, she said it was a shock to realize just how fragile the family structure has become.

"It's lucky my mother is helping to take care of my son," said the 24-year-old, who is juggling the family's grocery store in Beijing's Chaoyang district with caring for her hospitalized father.

"Sometimes I fear that if my parents died, I would be left alone in the world all by myself," she said, fixing her reddened eyes on the half-empty coffee cup in her hand. Her husband Wang Xiaobo, 25, is studying for a post-graduate degree in Hefei, capital of Anhui province, and can only return for short periods.

"He fell asleep at the hospital when he was taking care of my dad," complained Li Jinya. "I know he is tired - I'm tired too - but this is my father's life we're talking about."

The feeling of insecurity has led to tension and many arguments at home, she said. "I can't sleep these days. I feel I should go to see a therapist but I'm too scared."

Changing attitudes

Even though two people from single-child families can legally have a second child under China's family planning policy, surveys show that the enthusiasm among urbanites for larger families is dwindling.

The reasons for this are many. However, the biggest effect is a growing level of insecurity about the future.

"When people see that traditional family values are being weakened, they start to worry," explained Sun Yiqun, a research director at the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. "This is compounded by concerns among the elderly and middle-aged that there isn't a sufficient social support network."

Bupa, a British healthcare organization, recently polled 12,262 people in 12 countries on their attitudes toward ageing and found almost one-third of Chinese respondents admitted they feel depressed when they think about getting old.

This could suggest why suicide rates among the elderly in urban areas have seen such a worrying increase in recent years.

According to Jing Jun, a sociology professor at Tsinghua University, the annual suicide rate among 70- to 74-year-olds surged to more than 33 for every 100,000 people between 2002 and 2008, up from an average of 13 in the 1990s.

The number is even higher in rural areas, where economic pressures and the migration of farmers to cities have weakened the social status of senior citizens. A 2008 study of villages in Hubei province by Huazhong University of Science and Technology found suicide "is a culture" in some villages, with the elderly often taking their own lives after family arguments or when they feel they can no longer work.

"The new family structure is not only about the changes in lifestyle and values between young and old," said professor Yuan. "Smaller families mean simpler relations, making society overall more detached."

As well as having the world's largest population with 1.3 billion, China also has one of the fastest ageing rates.

The number of people aged 60 or above stood at 167 million in 2009, almost 13 percent of the population, according to the China National Committee on Ageing. With feelings of insecurity on the rise, experts say families must prepare for the future, while the need for the government to create a better social security system is growing urgent.

"We've had some good examples of private-run nursing homes but the number of places (offered for the elderly) is far from meeting demand," said Zhong Changzheng, spokesman for the China National Committee on Ageing.

Policymakers are encouraging diversified services for the elderly, he said, as well as advocating a change in attitude toward placing relatives in nursing homes, which at the moment is seen as an "undutiful act".

Authorities are also promoting community-based care services and facilities so older generations will be able to receive help in their own homes. Hotlines launched in Beijing also offer professional advice on care options.

The capital alone is home to 2.6 million people aged over 60, putting nursing homes places and assisted care apartments at a premium. This has resulted in many property developers starting on residential projects aimed at filling the needs of 4-2-1 families.

In Shanghai, where more than 20 percent of the population is classed as "elderly", workers can now postpone their pensions for five years and carry on working after the mandatory retirement age (60 for men and 50 or 55 for women, depending on their status).

The move, which was introduced by the city's human resources bureau on Oct 1, is aimed at addressing a financial shortfall in the social security fund. However, critics claim it will reduce the number of opportunities in an already tough job market.

Family investments

For those who can afford to, investing in property remains one of the preferred choices for families looking to prepare for the future.

"Being a landlord is my own way of preparing for the gloomy days of getting old," said Li Xue, 32, who has a 5-year-old son and rents out three apartments in Beijing's downtown area.

Jia Xuan said her parents have also sold their three-bedroom apartment in Tianjin's Hedong district and are buying a bigger house for the whole family in the city's eastern suburbs.

The move will mean a longer commute for the couple but it will allow their daughter to spend more time with her grandparents.

"The community has better child care services and we will have more room for the family," said Jia, 28.

She said she feels guilty about using her parents to help take care of their child but, as the mortgage accounts for almost half of the couple's income, they cannot afford a nanny.

"After we got married, my parents urged me to have baby early so they would still have the energy to help with the baby," said Jia, although some experts warn that the heavy involvement of grandparents can lead to conflicts due to their different views about education.

Jia and her husband Li Wenbo, 31, know the challenge they face in caring for their parents in the future, but for the time being are focusing on finding the right kindergarten.

"Right now, it's OK because our parents are still healthy and can take care of themselves," said Jia, "but we need to plan ahead."