Focus

Watching the detectives

By Cao Li (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-21 08:09

|

Large Medium Small |

|

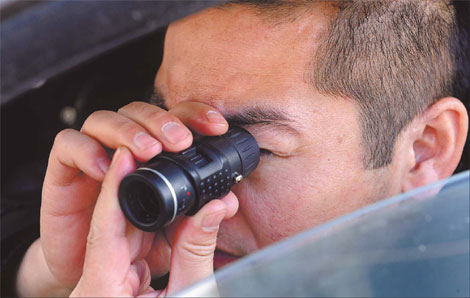

Zheng Yuxin, founder of Gelei Business Investigations, stakes out a property from a car. His firm is based in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, and is regularly involved in IPR crackdowns. Zhang Wande / For China Daily |

Private investigators and legal experts call for tighter control of agencies in bid to protect rights and fight corruption. Cao Li in Beijing reports.

Wang Yu stood in the street covered with thick layers of clothes, his face hidden by a scarf, mask, glasses and hat - and it was not just because of the cold weather.

For two weeks, he has been staking out a small house from across the street from morning to night. When the owner emerges, he follows him in the hope of completing his mission: uncovering an underground network trading in counterfeit cigarettes.

As a private investigator, Wang is assisting Anshan's industry and commerce bureau in northeast China's Liaoning province with its massive crackdown on fake goods.

His previous client was a 40-year-old woman in Beijing who hired him to track her cheating husband for 24 hours a day to collect evidence for a divorce. His next will be to trace a missing teenager who is believed to have run away with friends from the Internet.

Wang, who did not want his real name to be used, and his fellow detectives have seen a steady increase in demand for their services in recent years. Yet, despite their success in China, they are now the ones being investigated, over accusations of privacy violations and the use of illegal methods and devices.

A revision to the country's Criminal Law in 2009 that outlaws the trading of personal information has also put detection activities under further scrutiny.

Former soldier Yuan Zheng, 33, will spend the Spring Festival holidays in a Beijing prison for illegal possession of personal information. He will serve a year after being convicted at Haidian District People's Court in December.

He established Dongfang Mosi Business Investigation in June 2009 with his partner, Yong Zhengde, a 36-year-old man who can barely write his own name (he is also serving one year in prison). Their services included collecting debts, probing allegations of infidelity and collecting personal information. When police raided their offices in 2010, officers found a range of devices, including hidden camera equipment.

"This is a new crime," said Zhang Peng, a judge at No 1 Criminal Court who presided over Yuan's case. Of the six charges of illegal possession of personal information he has tried, two involved private investigators. "They illegally obtained personal information, such as bank and residency details, assets and phone records, and sold them for money," said the judge.

According to Chinese law, only police and State security officials can legally gain access to personal information to investigate crimes. Zhang added: "The use of personal information must be under strict control. Otherwise it could be used to facilitate crimes."

In Yuan's defense, a client surnamed Chen argued in court that, in litigation, people have to provide evidence to support their claims, yet most people do not have the ability to collect it and lawyers are unwilling to take on difficult jobs. "Why not let them do it?" he said in an interview with Procuratorial Daily, a periodical published by Supreme People's Procuratorate.

Since the first private investigation firm was founded in Shanghai in the 1990s, the number of detectives has risen to more than 200,000, despite repeated judicial attempts to outlaw the business.

The Ministry of Public Security banned private investigations in 1993 to stop detectives exercising powers that are exclusive to government law enforcement. Nine years later, however, the Supreme People's Court released a contradicting directive that allows the use of evidence collected through secret video and sound recordings.

To get around the revised Criminal Law, which hit the industry hard in 2009, vast numbers of detectives registered as business consultants instead of investigators. This allowed them to operate in a gray area, free from effective regulation.

With the increase in demand brought on by China's economic and social development, the number of litigations has also risen sharply. So too has the use of illegal methods and devices by private detectives.

Tao Xinliang, a lawyer and dean of Shanghai University's intellectual property school, said his law firm hires private investigators to collect information because "violations are rampant and obtaining evidence is becoming more difficult".

Legal gray area

For many companies, finding counterfeit goods is an impossible task without detective services. A public relations manager at a major US-based pharmaceuticals company, who did not want to be named, told China Daily his firm uses them to trace fake medicine.

The owner of a Beijing investigation agency, who asked to be identified only as Yu, said business is on the rise and that half of his clients are women suspicious about their husbands. He also collects debts and searches for fake goods.

"Ages of clients range from early 20s to late 60s," he said. During an hour-long interview, he answered his phone every few minutes to answer inquiries from potential customers.

Although business is good, Yu admitted he is feeling under pressure to be more disciplined as police are watching closely. "We don't use tracking devices any more as they're illegal (under Criminal law)," he said, "All my colleagues and I do is follow."

With a smile, he added that if private investigators do their job properly, police officers will be able to take more holidays.

Chen Wei, founder of Jilin Fuer Social Issues Investigations based in Changchun, said he is receiving more work tracing missing people, with cases rising from about 30 in 2008 to 50 last year. Subjects are usually teenagers on the run with cyber friends and adults who are victims of scams, said Chen, a former police detective who has been in the industry for 11 years.

"We investigate cases that the police don't accept," he said, adding that, for cases in which companies want to protect their brands, going to the government can often take too long. "(Authorities) don't have the staff to cope."

Shanghai SDE Business Information Consulting Co Ltd, which investigates claims of corporate espionage and bribery, has also seen demand grow 30 percent, according to general manager Wei Yingjie.

The annual Lunar New Year holiday, which this year runs from Feb 2 to 8, is the busiest time for many detective agencies.

"Recently, we have mainly investigated fake products ahead of the New Year shopping period," said Zheng Yuxin, founder of Xinjiang Gelei Business Investigations in Urumqi. "We spend weeks cooperating with industry and commerce bureaus to crack down on fake wines, brandy and fireworks."

Although surrounded by an air of mystery, most private investigators are actually former police officers and army veterans. Many have poor education backgrounds and simply slipped into the industry after struggling to find civilian jobs.

"The public generally misunderstands the profession and equates us to the mafia," complained Beijing agency boss Yu. "Someone once called me and said his friend wouldn't leave his house. He wanted me to scare this friend away. I don't take cases like that."

However, like every other detective who agreed to talk to China Daily, Yu accepts the industry has its good and bad operators. Some investigators take deposits but do not do any work, while even "good ones sometimes resort to illegal methods", he said.

Getting connected

Last September, authorities in Chongqing executed detective agency boss Yue Cun after he was found guilty of running a criminal gang. According to the municipality's No 5 Intermediate People's Court, his gang committed acts of murder, intentional injury, blackmail and illegal detention and possessed illegal firearms.

Beijing courts also tried about a dozen cases in 2010 involving private investigators using illegal methods to collect debts, obtain personal information and track cheating spouses.

Some investigators interviewed by China Daily admitted using connections with police or government officials to get personal information, while others have accessed phone records, which violates privacy laws. One case heard at the capital's Chaoyang District People's Court involved investigators working with cell phone services companies to obtain details of target subjects.

Although judge Zhang agreed there is a need for such investigations, he suggests authorities set up departments and rules to stipulate what information professionals can use to justify their assignment. "It is hard to control the industry when it's in a gray area," he said. "It should not be supported by law unless there are strict and detailed rules on its conduct."

Many legal professionals and industry experts say investigation services are more helpful than harmful, as they facilitate and extend their clients' rights to search for the truth.

Private detectives cover cases that are out of the judicial system's range and help keep society safe, "but there should be laws defining conduct, to differentiate from cases dealt with by police", said Chen at Jilin Fuer.

Criminal law expert Cai Jie wants the government to go one step further, however, and give investigators "more power" than the public to carry out their services. "That way, they won't need to bribe governments or companies to access information," said the professor at Wuhan University's law school.

As investigators are now being hired for a wide variety of cases, industry insiders say they believe their services will be legalized in the future.

Xinjiang Gelei Business Investigations used to deal mainly with cheating spouses, but in the last few years its client base has shifted to firms searching for fake goods, including international corporations like Nestle and L'Oreal, according to Zheng.

Meng Guanggang, one of the first and most well-known private investigators in China, said he also now focuses more on business information security.

"For the past two years, I've been employed by a company to provide security advice on intellectual property rights protection or investment safety," said the 56-year-old. That is the future of the industry, he said, "and as competition gets more fierce, more companies will need those services".

The only problem is, with detectives operating free of effective regulation, who is ensuring they are qualified to do it?