Food security to be concern in 2012

Updated: 2011-12-28 09:14

By Zhou Siyu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

China to rely more on foreign food suppliers to feed population

BEIJING - The year 2011 began with fearful memories of the 2008 global food crisis. That was a time when surging food prices swept the world, giving rise to riots, trade bans, and panicked hoarding. Millions of people standing on the verge of poverty fell back into the pit. To many, the threat of hunger and malnutrition once again loomed on the horizon.

|

|

|

Harvest time at a farm in Nantong, Jiangsu province. Having achieved higher grain output for an eighth consecutive year, China faces intense pressure to keep expanding its grain crop in the coming years. Among the hurdles, analysts say, are the depletion of natural resources and demand from an expanding population.[Photo/China Daily] |

|

|

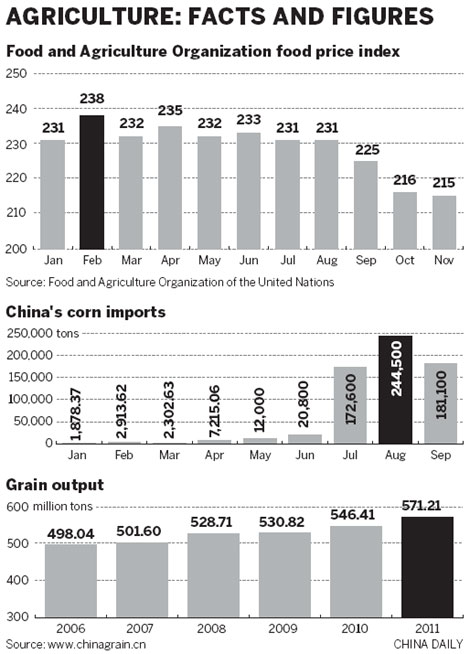

In February, the global food price index, established by the United Nation's Food and Agricultural Organization, increased to its highest point since it came into existence in 1990.

Governments in some developing and less-developed countries were particularly frustrated, as high food prices foiled their decade-long work to reduce poverty, led to resentments and upset social stability. Analysts said discontent with surging bread prices helped provoke the widespread uprisings in the Middle East.

During recent years, food price hikes have suggested that the low prices that were common since the 1970s have ceased to exist. That comes at a time when more mouths than ever have to be fed. The world's population is expected to increase from 7 billion this year to 9 billion in 2050, according to a projection by the International Monetary Fund.

The basic economic task of feeding the world's hungry has once again become daunting.

Various places' means of dealing with the approaching difficulties are likely to be different. In China, agricultural producers are fighting a battle on two fronts: they are simultaneously contending with a surge in demand stemming from the ever-increasing population and with a decrease in the amount of arable land, water and other natural resources that can be exploited.

The country's looming troubles help explain why it has imported more agricultural goods in recent years. Not until 1996 did the country begin to import soybeans. By 2010, though, China was bringing in 54.8 million tons of the beans a year, making it the largest importer of that farm product in the world.

The rising demand for soybeans was partly driven by a change in people's dietary habits; many had shifted away from having mostly grains on their plates to having more oil and meat, said Cheng Guoqiang, a senior fellow at the State Council's Development Research Center, a State think-tank.

Soybeans are also used widely in China to produce cooking oil and in animal feed. According to Cheng, every person in China consumed 18.3 kg of edible oil on average in 2011, compared with 11 kg in 2001. Pushed upward by urbanization, the figure is expected to rise to 23 kg in the next 10 to 15 years. "The increase in soybean imports in the long term is inevitable," Cheng said.

To meet the demand, production must increase. China has managed to harvest more grain every year for eight years in a row, starting in 2003. This year, the country had a record grain output, amounting to 571 million tons, 4.5 percent more than the year before. Enough grain has already been produced to meet the government's output target for 2020, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

But the depletion of natural resources threatens to undermine harvests in the years to come. In 2012, the country will be under "great pressure" to secure yet another increase in grain yields, said Chen Xiaohua, vice-minister of agriculture.

Han Jun, deputy director of the State Council's Development Research Center, said "seeds, water and land" will be essential to China's further development in agriculture.

Seeds of doubt

Seeds have long been a cause of concern for many observers of China's agriculture industry, not because of their performance but because of their provenance. Industry data show that corn seeds from Pioneer Hi-Bred International Inc, a subsidiary of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co, were sown in more than 2 million hectares of the country's cornfields up to 2011. One variety of Pioneer's seeds has become the third most common in the country, analysts said.

In the vegetable seed market, foreign companies have 15 percent of the market share for those products in China, according to data from the Ministry of Agriculture. The figure indicates their formidable presence in China's seed market, analysts said.

Worryingly to some Chinese observers, foreign companies continue to expand. In September, Monsanto Co, the US-based crop-biotechnology company, and Sinochem Co, China's agricultural-chemicals conglomerate, invested 500 million yuan ($77 million) in a factory that processes corn seeds in Northwest China's Gansu province, according to reports by domestic media.

Many multinational seed companies say they have only taken a small bite of China's big pie. Monsanto's revenue from China made up less than 1 percent of the company's total revenue in 2010, it said, adding that it is looking to increase that percentage.

China has more than 8,000 domestic seed companies. Most of them are small and have little capacity for research and development.

"They are vulnerable to their foreign rivals," said Ma Wenfeng, a senior analyst at Beijing Orient Agribusiness Consultant Ltd, one of the largest consulting companies in the industry.

The Chinese government has tried to bring order to the seed market. In April, the government issued guidance that "encourages mergers and acquisitions between seed companies", and aims to "foster companies" with international competition.

To fulfill the guidance's purpose, Han Changfu, agriculture minister, said in December that the nation will support the development of 20 large domestic seed companies.

Water, land

Whatever entity produces the seeds, they will still be planted on China's farmland. And the fertile arable land in China is mostly concentrated in the north, where water is scarce.

What's more, irrigated land is extremely productive, making water even more important. The modern technique of drip-feed irrigation can reduce the use of water by 50 percent while boosting grain production by 25 percent, agricultural experts said. In 2011, governments at all levels spent 33.4 billion yuan on water conservation.

Preserving farmland also requires hard work. The amount of arable land in China has decreased every year in recent times, thanks largely to the expansion of sprawling cities. Skyscrapers now stand on land that once contained fertile fields.

The overuse of agricultural chemicals, in the meantime, has contributed to the degradation of farmland. Some farms have been harmed by the improper use of chemicals and their productivity has plummeted. The overuse has also led to pollution and put the nation's food supply at risk of contamination.

Bad weather has also taken a toll. At the beginning of the year, many of the leading provinces for food production were hit by an unprecedented drought. China grows more wheat than any other country and fears about the drought's consequences have sent the price of the grain fluctuating throughout the world.

By and large, this year's natural disasters have had only a "moderate" effect on agricultural production, Han Jun said. "Food security remains the weakest link in China's national economic security," he added.

No easy fix

To spur agricultural production, the government plans to rely on technology. The government will invest more than 4 trillion yuan over the decade following 2012 in seed breeding, livestock raising and agricultural transportation and storage, according to domestic media.

But technology takes time to work its magic. In 2011, the prominent Chinese scientist Yuan Longping cultivated a new breed of hybrid rice and set a world output record in September when he showed 13.9 tons of rice could be grown in a hectare. Agricultural experts estimated that it will take from three to five years for the company to plant the variety widely.

With so little arable land and water, the country should look to make better use of irrigation and better and proper use of fertilizers, said Cheng Guoqiang from the State Council's Development Research Center. That should help boost the production, Cheng said.

Pressed by surging oil prices, the price of agricultural inputs such as chemicals and fertilizers has increased. China has also seen labor costs rise in recent years and that has further squeezed farmers' profits. The provinces where much of the food is grown in China are still relatively poor, especially in comparison with the country's wealthy coastal region.

In Henan province, a main food basket in China's heartland, efforts to preserve farmland make it difficult for the government to take idle land for the development of cities, said a local official.

"In some of the provinces that produce much of the country's food, agricultural production seems to have become a burden," said Han Jun from the State Council's Development Research Center .

A yawning market

China has found it impossible to grow all of the food it needs and has consequently formed closer ties with the world food market.

Many have benefited from the country's growing demand. In 2011, China surpassed Canada to become the largest importer of US agricultural goods, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Agricultural imports supported more than 1 million jobs in the US. By the end of 2012, the value of US agricultural exports is expected to reach a new high of $137 billion, the department said.

China's trade in agricultural products with African and Latin American countries is also expected to increase. The country was expected to start importing Argentine corn in 2013.

Against this background, the concern about China's food security seems more reasonable. The total amount of food traded in the international market can hardly meet half of China's demand. The world cannot afford a failure as big as China.