No one profits when business is bad

Updated: 2012-06-04 07:21

By Xu Junqian (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Commercial disputes can easily occur between different cultures, reports Xu Junqian in Yiwu.

|

|

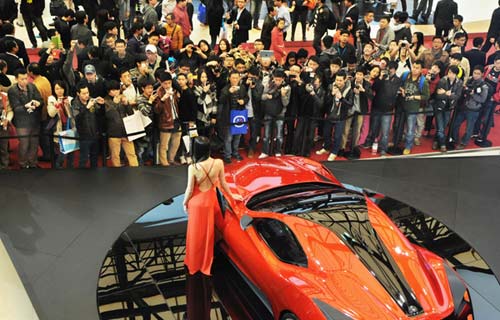

This 2011 photo shows Indian businessmen purchasing Christmas products in a local international trade center in Yiwu city, Zhejiang province. Zhang Jiancheng / for China Daily |

Gulshan S. Asnani's office is decorated with a small woolen wall carpet featuring exotic patterns from his hometown in India and a man-sized Malabar chestnut, or money tree, a pot plant the Chinese believe will bring good fortune.

These weirdly matched items symbolize the way the 35-year-old trader has been conducting business for the past decade in the city of Yiwu, Zhejiang province. He's combined a touch of India, which, as he sees it, is boldness, with the Chinese characteristics of diligence, intelligence and, perhaps, a little bit of cunning.

Asnani has always been proud of this "When in Rome" attitude, which has helped him develop a multimillion-yuan company. That is until recently, when what the locals call the "Indian thing" occurred.

|

|

"The attitude of the Chinese businesspeople in the market has changed totally. They have become as wary as cats, especially once they know that you are from India," Asnani said.

The "Indian thing" was highlighted in May, when a trader called Danish Qureshi was illegally detained at the apartment of a Chinese woman named Wang over a debt dispute. According to the Hindustan Times, Qureshi's employer, an Indian businessman called Faisal, had defaulted on service fees of 50,000 yuan ($8,000) and on payments for purchased goods of 400,000 yuan owed to Wang. Quareshi was discovered and freed by local police after three days, and Wang was detained.

The incident gained wide attention within the business community. Two days after Qureshi's rescue, the Indian embassy in Beijing issued a safety advisory notice "cautioning" Indian businesspeople against doing business in Yiwu and warning of dangers such as "curtailed freedom of movement".

In the past two decades, Yiwu has developed from an obscure town with neither geographical nor natural advantages into the world center for small commodities such as hair clips and zippers. That growth has attracted traders from around the world, looking to ship cheap Made in China goods back to their home markets.

Government statistics show that more than half of Yiwu's population of just under 2 million are non-native residents. The number of foreigners is 13,000 from 197 different countries, outstripping the overseas populations of other large cities in the province such as Hangzhou and Ningbo. More than half of the foreign residents are of Middle Eastern origin, from places such as Yemen and Egypt. The city also plays host to a transient population of 420,000 foreign businesspeople.

The advisory notice was the second the Indian embassy issued this year. In January, two Indian businessmen were held in similar detention by their Chinese suppliers and, according to the newspaper India Today, "are still fighting their case".

While the advisory has not been "taken seriously" by Asnani and many others in Yiwu, both Chinese and foreign entrepreneurs in the city have been dealt a heavy blow. "It reminded us that there seems to be something wrong with the apparently perfect chain of foreign traders and Chinese suppliers", said a Yiwu producer of accessories, who would only gave his surname as Zhou.

"The city's growing reputation has not only brought more deals, but also frauds from all over the world who want to make easy money. Moreover, some Chinese manufacturers have been too desperate to seal deals with traders, leaving many loopholes," he added.

To survive in the ever-competitive market, a supplier would sometimes agree to manufacture thousands of items without asking for a deposit, or would allow previously unknown traders to ship products home and settle the account at a later date.

Asnani shared Zhou's opinion. He said that problems of this type are always likely to happen "sooner or later" if business continues to be conducted in an "unbusiness like manner".

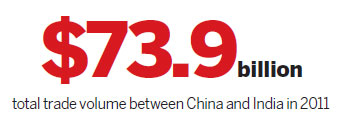

Growth of trade

The reason these incidents were both centered on China and India is because of the high trading volume between the two countries. Statistics from Xinhua News Agency show that in 2011 bilateral trade between China and India was valued at $73.9 billion. That made China its neighbor's biggest trading partner for a second consecutive year.

The agency quoted an Indian official as saying that Chinese manufacturers have become increasingly interested in the Indian market because of the recession affecting Western countries, the traditional export destination for China.

Zhang Hong, director of the liaison department at Yiwu Foreign Service Center, said the most common problem between foreign traders and Chinese manufactures is inconsistency in quality between samples and the finished product.

"Nine out of 10 disputes result from discussions along the lines of 'It (the finished product) is not as good as the sample'. That's then followed by arguments about paying less than the agreed price," said Zhang.

Zhang's department offers a range of services to overseas businesspeople, including company registration and conflict resolution. According to him, the center is contacted by around 10 foreign traders every month with reports of business conflicts. Usually, only one or two of those cases can be settled to the satisfaction of both parties. Moreover, the number of cases is reported to be rising, partly because overseas entrepreneurs are becoming more suspicious and partly because close collaboration has led to growing familiarity between the two groups and each is aware of the others' weaknesses.

Alhamed Adhali, from Yemen, was one of the first foreign businesspeople to arrive in Yiwu. He recalled the "simple and glorious past". "Accidentally" introduced to the city in 1998, when the name wasn't even familiar to most Chinese, Adhali started the Golden Source Trading Co by "sharing one translator with dozens of other foreign businesspeople, because there was only one in Yiwu who knew anything about the region and could speak the language.

"It was very interesting. Sometimes you would have to wait for hours for a very brief, one sentence, talk to your business partners. On other occasions, the translator just disappeared with other foreigners, leaving you and your Chinese partner with an hour of silence and awkwardness," he said.

But for Adhali, the early days were the best times, despite the language barrier and the then unsophisticated nature of Yiwu. Things have changed and he now speaks better Chinese than English.

"There was more trust and sincerity between sellers and buyers at that time," he said. "Now there are expats on tourist visas arriving to grab what they can and the locals have become hostile and more inclined to fool us."

However, Wei Bin, who owns a translation company in Yiwu, said the increasingly close connections between Chinese and foreign businesspeople are the main cause of the growing number of conflicts. "It's just like an international marriage. At first, the Chinese family and, say, the foreign daughter-in-law, will treat each other with due respect and courtesy. But as the days go by, familiarity breeds contempt and problems occur," he explained.

Wei's company was authorized by the government as an official translation service to provide foreigners with help in disputes two years ago. He said the service has witnessed an increase in business relating to legal cases in that time. "We now receive four to five cases of this type every month, ranging from debt disputes to conflicts between foreigners and their neighbors," said Wei.

Tip of the iceberg

Zhang, the government official, said that the number of disputes in the public domain might be the tip of the iceberg because most foreigners won't turn to government departments or public organizations when they have a problem.

That came as no surprise to Asnani. "We prefer to ask for help from our Chinese friends or translators, because once we make the problem public, many of our business secrets will be known," he said.

"If our personal connections are unable to help us and the problem doesn't actually interrupt our daily business, we just leave it unresolved," he added in a frustrated tone.

However, Ko Hee-jung, the president of the Korean Chamber of Commerce in Yiwu, believed that problems can always be worked out as long as there is a common interest such as, in the case of Yiwu, "making money honestly".

"We are the most united and comfortably settled expats living in Yiwu," he opined, sitting in the chamber's cramped office, which is tucked away in a corner of Yiwu's International Trade Mart.

Founded in 2000 as the first officially registered chamber of commerce for foreigners in Yiwu, the KCC currently has 500 members, and each pays 100 yuan a month to help cover expenses. "It's not compulsory. But very few have ever missed a month," said Ko. "That's because in the last decade, the KCC has become a shelter, a social club and, more importantly, a platform for business meetings for the 6,000 South Koreans in Yiwu."

Even though the two countries share many aspects in terms of culture and lifestyle, the chamber is dedicated to helping businesspeople better communicate with local government, organizations, and companies. It also aims to help its members' families to better adjust to life in Yiwu, through activities such as sports meetings and outings.

"In South Korea, almost every businessperson knows about Yiwu. We don't need to tell them how much gold is hidden in this city. What we need to do is to help our folks to avoid standing on a landmine while digging for gold," added Ko.

Eighty percent of the hair clips, earrings or boxes of soap in South Korean markets and shopping malls are made in Yiwu according to the KCC. Almost all South Korean businesspeople in the city are middlemen who bring designs and materials from South Korea and then ship the finished products back to their homeland and, sometimes, around the globe.

"Recently, we've been helping college students in the South Korea find internships in Yiwu," said Ko. "As for those who want to realize their ambitions in the business world, this manufacturing center is a pretty good starting point."

Contact the reporter at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|