Workers overseas: In and out of Africa

Updated: 2012-06-11 08:14

By Hu Yongqi in Dingzhou, Hebei (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

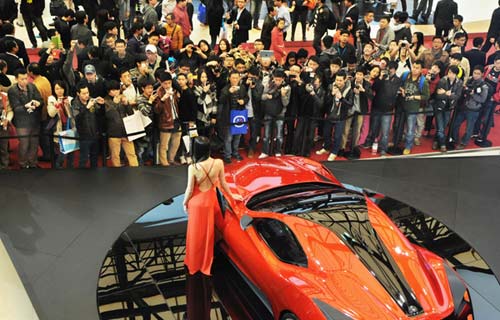

Lujiazhuang only shows signs of life when the children come out of school. Many of the residents of the village in Dingzhou city, Hebei province have worked overseas, mostly in Africa. Photos by Kuang Linhua / for China Daily |

|

Above: Bian Zili, 47, recently returned to China from Kuito in Angola. Below: An air ticket outlet in the center of Lujiazhuang village. According to its owner, Sun Fengtao, about 300 locals buy tickets at his outlet every year. |

Workers discover that Africa can be both rewarding and risky, reports Hu Yongqi in Dingzhou, Hebei province.

For large parts of the day, Lujiazhuang, in Dingzhou city, looks like a ghost town. Few of the 3,000 registered residents walk along the streets, bordered by two-story houses. The only faces visible belong to the young or the elderly. People of working age seem few and far between.

The only time the village shows signs of life are during the noon break or at dusk, when the kids come out of kindergarten and elementary school, playing the old game of throwing schoolbags at each other to see who can be knocked off their bike, amid much giggling and shouting. However, at nightfall a hush descends on the streets and everything is quiet once again.

In common with many villages in China, much of the workforce has moved away in search of well-paid jobs. Visitors may be surprised to see a shop selling air tickets, right in the center of the village, but Lujiazhuang has more than 500 men who regularly work overseas.

Every year, about 300 locals buy tickets at the shop. The owner, Sun Fengtao, 40, said that about 70 percent of the village's labor force works abroad. About 10 years ago, 90 percent of those workers headed for Africa.

However, things don't always go smoothly. Last month, Nigerian immigration officials arrested 100 Chinese for living and trading in the country illegally. Although 70 were soon released, the incident highlighted the precarious nature of the lives of these Chinese nationals looking to find their fortune in Africa, where opportunities and risks coexist. However, as wages rise in China, many of the emigres are considering returning home for good.

Good earnings

Unlike many villages in Hebei province, almost Lujiazhuang's houses boast magnificent interior decor. Gao Zhenyao, 53, built a 10-bedroom house with the money he made operating cranes in Africa for 17 years. Following Gao's instructions, his wife ensured that each room was fitted with a wooden floor and contained a pair of sofas. Computers and Internet access were high on his must-buy list, even though he didn't know how to use them. Gao, who never attended school because his father was unable to afford it, said he wanted his grandchildren to enjoy "the most advanced means" of education.

In 1995, he joined a construction company working in Mauritius. Although the job was tough in the hot climate, he managed to stick it out and earned approximately 70,000 yuan ($11,000) in the first year. Every year his salary increased and by 2009, making 10,000 yuan a month was a piece of cake.

The exodus from the village began in 1989, when poverty drove the locals to find new ways of making money. At that time, the only way to make a living was by farming. Each family had 0.84 hectare of land on average, so small that it could only produce enough food for each family's needs. Villagers were desperate to earn more money to cover daily expenses and the fees for their children's schooling - because the village was not included in China's free compulsory education system until 1999.

In 1989, Li Zhenying, now 56, began recruiting workers for a company that was building hospitals in Accra, Ghana. The employer promised to pay 15,000 to 20,000 yuan a year, 10 times more than the villagers could make at home.

However, the villagers were hesitant as they vacillated between their thirst for money and fear of the unknown. "Ignorance of the outside world became a fear of going abroad. People even questioned if we would come back alive," said Gao Zengxin, one of the trailblazers.

"But we had no choice. Poverty was like a mountain weighing down on us, and I had to take the first step," he said. Eventually, four other men joined Li and Gao on the project. The six signed two-year contracts and departed for Africa. Their families didn't hear from them for the next two years and rumors spread that they had been killed.

However, in 1991, Gao returned with 30,000 yuan in cash and a color TV set, a luxury appliance in those days. On his first night at home, he became a lecturer when neighbors swarmed into his thatched house, which he soon upgraded to a two-story building. "I could see the eagerness in their eyes," he said.

For the 10 years that followed, the villagers benefited from Chinese-aided construction projects in African countries. Although the men had little knowledge of high technology, they were experienced in construction work, especially in the fields of carpentry and bricklaying.

Some of the more ambitious increased their incomes by setting up their own businesses. Most of them were contracted to hire people from neighboring villages to work on projects. Guo Pingliang, 48, worked as a carpenter in the Angolan capital, Luanda, from 1997 until 2007. When he had amassed savings of 600,000 yuan, he hired 10 people, using his savings to pay their wages. They worked as a part of team constructing an athletics stadium in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the project brought Guo income of more than 200,000 yuan.

Roughly 2,000 Dingzhou residents are currently working overseas and international migrant workers from Lujiazhuang earned a combined 50 million yuan last year.

Sun Fengtao, the air ticket vendor, said that more than 90 percent of workers from Lujiazhuang went to Africa before 2002, but now most prefer Singapore, which is regarded as being much safer.

According to An Pengfei, manager of the Jianghai International Labor Agency in Dingzhou, only 200 out of 1,000 workers provided by his agency went to Africa last year. The shift began as people began to learn more about working conditions in Africa increased and decided that the continent was no longer a desirable place to work.

Bad environment

Along with 10 co-workers, Bian Zili left Kuito in Angola last month. Their project is not complete, but the boss has decided to suspend work because of turmoil during the presidential election. The 47-year-old from Xiliuchun, a village that neighbors Lujiazhuang, felt confined and saw potential danger everywhere.

In August, he traveled to Angola to work as a carpenter. When he arrived at the airport in Luanda, he was stopped by a security officer who searched his bags. Nothing untoward was discovered, but the officer did not let him go. "Where is the dollar?" the officer muttered to himself.

Bian was dumbfounded because he didn't understand what the officer meant. However a translator explained that the officer wanted cash to smooth the way. Bian gave him 10 dollars, but the officer didn't give up. "He was waiting for 30 dollars and showed me three fingers to indicate that," said Bian. It didn't end there, though, and Bian had to pay another $30 at the airport on his way out of the country. "You know, 30 dollars is not a big deal, but the point is I felt like I was being robbed," he said.

In addition, Bian and his co-workers dared not to step out of their construction site. His employer repeatedly emphasized just how dangerous that would be. The language barrier was one obstacle, but what really made his boss nervous were crimes such as robbery and even murder.

"I was scared and just slept or talked to my wife via an instant messenger service after 10 hours hard work each day," he said.

Meanwhile, many of the Chinese workers were unable to get accustomed to the tropical weather. Many were affected by malaria and the Chinese medicine the company bought had little effect. At one point, Bian spent four days in a malaria fever. His condition was so bad that his colleagues even called his wife. Fortunately, he recovered fairly rapidly. "Although the pay was very good, the place was really bad and I won't go there anymore," Bian said.

A risky assignment

However, Bian was lucky to be working with co-workers and bosses, individual Chinese businessmen in Africa have had to face all the risks alone.

There are no official statistics regarding Chinese workers in Africa, but the number is estimated to be 1 million. Half of the 20,000 Chinese in Kenya are construction workers and the other are private businessmen, said Han Jun, president of the Overseas Chinese Federation in Kenya.

About 20,000 Chinese immigrants work in Nigeria and the northern city of Kano is home to the largest textile trade market in West Africa. More than 300 Chinese shops have operated there for 20 years. Now, increased competition in China and plummeting demand from Europe and the US have seen more Chinese merchants turning to Africa.

Safety, immigration officers and inequitable taxation are the three main concerns for Chinese businessmen, said Wang Qiang, secretary general of the China-Africa Chamber of Commerce in Kano.

He believed that Chinese merchants in Kano are especially vulnerable to crimes such as robbery and burglary. On May 28, one of the Chinese workers in Wang's neighborhood was robbed in his home. All his cash, his computers and even kitchen knives were taken, but he did not dare to fight the thief. "The robbers will do everything to cover up their crime. If you fight, they will kill you without hesitation. So every time the robbers come to me, my first idea is that money can be earned, but that life only happens once," said the victim, who declined to be named.

Wang said Chinese workers often have difficulty obtaining work permits and permanent residency. Many get their visas through links with officials, according to the unnamed trader. However, Chinese workers are usually targeted by immigration officials ahead of all other ethnic groups. "The best way to clear things up is by giving them money. Usually, I have to ask my local friends for help. They negotiate with the officers to let us go," said the unnamed trader.

Wang remembers how immigration officials arrested textile traders last month. "The officers did not ask whether we had visas or passports, they just came and took some people away. Some had only been in Kano for two days," he said.

Before 2010, the country's textile industry was hugely profitable and merchants could make a net profit of as much as 70 or 80 percent. However, as that figure has now fallen to 10 or 20 percent, many traders are considering setting sail for home.

Need more help

Africa still has plenty of potentially immense markets, such as Nigeria, according to Han Jun, president of Overseas Chinese Federation in Kenya. But he admitted that problems do exist, especially as many officials fail to abide by the laws, and the market has a great many loopholes.

Han suggested that foreign businessmen should be properly prepared before moving into the market, especially in terms of the correct documentation and at least some understanding of the local language.

"If you believe that money can solve all the problems, the local officials will get the impression that the Chinese are timid, but actually we are not," Han said.

Wang Qiang said that businessmen really need more help from the Chinese authorities, especially the embassies in African countries. "I hope that, with the support of our country, we can make a profit and build a better life," Wang said.

Contact the reporter at huyongqi@chinadaily.com.cn

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|