Iris Chang: A light in the darkness

Updated: 2015-12-14 08:06

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

||||||||

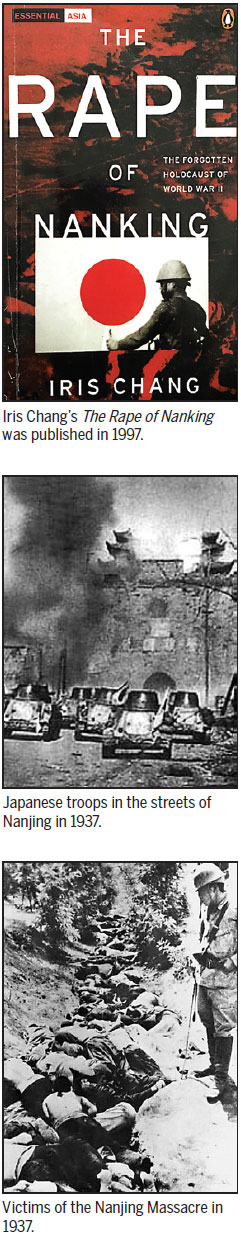

The author of The Rape of Nanking is best remembered for her harrowing account of the 1937 massacre that left 300,000 people dead and thousands more maimed for life. Zhao Xu reports.

"Loneliness is a silent chirp of a cricket across a lake

Where the leaves on the trees rustle at sunset.

It smells like a violet patch.

It sounds like wind blowing through the tall prairie grass ..."

|

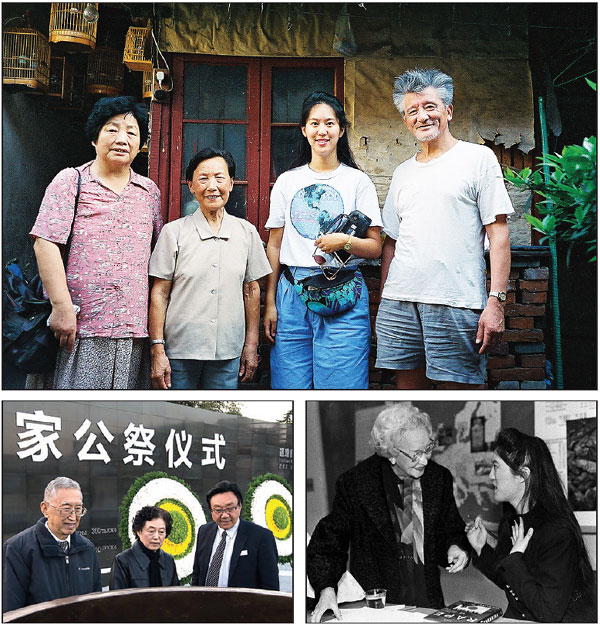

Clockwise from top: Iris Chang (second from right) interviewed Nanjing Massacre survivor Xia Shuqin (second from left) in 1995. Chang autographs a copy of The Rape ofNanking for a reader at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington in 1998. Ying-Ying Chang (center) and Shau-Jin Chang (left) attend the first national memorial service for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre, on Dec 13 last year. Photos Provided to China Daily and by Liu Yu / Xinhua |

Iris Chang wrote those lines in 1978, when she was 10, and 19 years before her harrowing book, The Rape of Nanking, brought her worldwide acclaim.

In 1995, at age 27, Chang flew from California to Nanjing in East China's Jiangsu province. There, under a crimson setting sun, she waded through the tall grass in an eastern suburb to reach a nondescript memorial stone dedicated to the victims of a massacre committed by the Japanese army in 1937.

That scene, and Chang's life-changing three-week visit, is described in moving detail in The Woman Who Could Not Forget, written by her mother, Ying-Ying Chang, and published in 2011, seven years after Iris Chang committed suicide. In December last year, Ying-Ying Chang visited Nanjing and, for the first time, toured the places where her daughter searched for a long-buried history.

The 75-year-old was accompanied by Yang Xiaming, who has spent years researching the six-week slaughter now known as the Nanjing Massacre. Yang accompanied Iris Chang 20 years earlier, as she gazed at the memorial stone.

"To see this young, vivacious woman, someone I had met just days before, go into a contemplative state of sadness was almost heartbreaking," said Yang, who acted as interpreter for the Chinese-American author as she spoke with survivors of the massacre.

"Their tragedy was only a tiny part of the one that started on Dec 13, 1937, when Japanese troops killed an estimated 300,000 civilians and unarmed soldiers, and raped countless others. But listening to the stories of people who crawled from under the heaps of bodies was enough to shake anyone to the core."

One such occasion involved an interview with Xia Shuqin, a massacre survivor who still bore the scars of the deep bayonet cuts.

"We went with Xia Shuqin, a 66-year-old massacre survivor, to her old house, where the killings took place when she was age 8," Yang said. "Pointing to the dilapidated wooden lattice windows, she told us that it was through those windows that she witnessed her family's horrible deaths. If you knew Iris Chang's family history, you would understand how those interviews must have resonated with her."

In March 1968, Iris Chang was born in the United States to Chinese immigrant parents. "Iris was a curious child," Ying-Ying Chang recalled. "When she was around 8 or 9 she kept asking us what we were doing at her age. That's really the beginning of her story."

On July 7, 1937, the war between China and Japan officially started, and in November, China's Nationalist Government announced that it was moving its capital from Nanjing to the southwestern city of Chongqing. A mass flight ensued. Ying-Ying Chang's father and his pregnant wife left Nanjing four weeks before the Japanese entered the city.

The family stayed first in the city of Guiyang, before moving to Chongqing, where Ying-Ying Chang was born in 1940. At that time, Shau-Jin Chang, her future husband and Iris' father, was living nearby, on the outskirts of the city.

Born in 1937, Shau-Jin Chang was age 6 months when his family arrived in Chongqing. Even now, almost 80 years later, he remembers the scene during the bombing raids.

"The Japanese were bombing virtually around the clock. Coming temporarily from the underground bomb shelter, I saw people outside with blood-splattered faces. I was about 6 at the time. However, my father told me that what happened in Chongqing was nothing compared with the suffering and carnage in Nanjing."

Despite having heard stories about Japan's wartime atrocities, Iris Chang was overwhelmed when she stood in front of poster-sized images of the Nanjing massacre at a 1994 conference in Cupertino, California, sponsored by the Global Alliance for Preserving the History of World War II in Asia.

"Nothing prepared me for these pictures - stark black-and-white images of decapitated heads, bellies ripped open and nude women forced by their rapist into various pornographic poses, their faces contorted into unforgettable expressions of agony and shame," she wrote.

By then, she had graduated in journalism from the University of Illinois, where her parents were both science professors. For the next three years, the budding writer was to plunge into a history that constitutes one of the darkest chapters of World War II, and produced a book that is "almost unbearable to read" but "should be read", according to Ross Terrill, an Australian academic, author and China specialist.

Iris Chang began her research in the US. In the Yale Divinity School Library, she read the diaries of Wilhelmina Vautrin, also an alumnus of the University of Illinois.

Born in 1886, Vautrin, a US missionary, was president of Jinling College in Nanjing at the outbreak of war in China. Turning the campus into a refugee camp, she helped save tens of thousands of Chinese, mostly women, during the massacre and afterward. "How ashamed the women of Japan would be if they knew these tales of horror," she wrote in her diary on Dec 19, 1937.

The stress took its toll, and having witnessed so much violence, Vautrin returned to the US in early 1940. On May 14, 1941, she took her own life.

Retracing old footsteps

Six months after reading the diary, Iris Chang was in Nanjing tracing Vautrin's footsteps, and discovering more about people and stories mentioned so frequently in the older woman's writings.

One of the interviewees was Li Xiuying, who was 18 years old and seven months pregnant in November 1937. She was stabbed repeatedly and was left for dead, until a fellow Chinese noticed bubbles of blood foaming from her mouth. Friends took her to the Nanjing University Hospital, where doctors stitched 37 bayonet wounds.

Unconscious, she miscarried on Dec 19, the day Vautrin made her diary entry.

"Now, after 58 years, the wrinkles have covered the scars," Li told Iris Chang, pointing to her own face, crosshatched with scars.

During her visit to Nanjing, Iris Chang was deeply disturbed not only by the inhumanity of war, but also by what she saw as a failure to mete out appropriate justice, according to Yang.

One of the survivors they visited lived in a room no more than six square meters. The old man was bathing, and the water in the small basin had almost turned muddy. "The way Iris moved her video camera - from the low ceiling to the soot-covered walls and the rubbish-clogged corridors - clearly indicated her mood," Yang said.

According to Brett Douglas, who married Iris Chang in 1991, all the information his wife gathered during her stay in Nanjing, was "distilled and filtered" in the writing process, when she was "working 70-hour weeks".

There was still research to do. After sending out more than 100 e-mails, Iris Chang received a reply from Ursula Reinhardt, granddaughter of John Rabe, a German businessman who, together with other Westerners, established the Nanking Safety Zone in December 1937, saving hundreds of thousands of lives. For the first time, the diaries Rabe kept during the war became known to the world.

From time to time, Iris Chang would call her parents. "She talked about her nightmares and her hair loss," Ying-Ying Chang said. "I told her to stop. But she said no. She said she wanted to speak for those who could no longer do so."

The Rape of Nanking was published in December 1997. "We expected it to sell 10,000 to 20,000 copies," Douglas said. "It sold close to 500,000 in the United States alone. The book remained at the top of The New York Times' bestseller list for 10 weeks, and was translated into Chinese the following year.

Accolades and attacks

Along with the accolades came the attacks, and the author was forced to defend the veracity of her account.

"She was fierce and fearless," Ying-Ying Chang said, referring to her daughter's appearance in a 1998 television debate with Kunihiko Saito, then Japan's ambassador to the US. After the ambassador spoke of events in Nanjing, Iris Chang turned to the presenter and said, "I didn't hear an apology."

On a personal level, the book continued to exert an influence on Iris Chang's life, long after she started working on other projects, Douglas said.

"For the last seven years of her life, people were contacting her with their own horror stories about the Japanese military, and people were approaching her trying to persuade her to write more books on the subject."

Then, in late 2003, Iris Chang began research for a possible new book on the Bataan Death March through the sweltering jungle on Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines, undertaken by US and Filipino prisoners of war.

In August 2004, Iris Chang flew to Louisville, Kentucky, to meet a Bataan veteran. Soon after arriving, she collapsed in a hotel room but later managed to have herself admitted to a psychiatric hospital. The doctor diagnosed "brief reactive psychosis".

"The Iris Chang I first met in October 1988 never came back," Douglas said.

Iris Chang killed herself on Nov 9, 2004. Messages of condolence flooded in, but her death also provided an opening for her detractors, who claimed that she had written The Rape of Nanking in a delusional state.

This is an assertion that her husband rejects. "Iris completed The Rape of Nanking in early 1997, but never showed any real signs of mental illness until 2004," said Douglas, who sees no direct connection between his wife's suicide and the horrors she endured writing the book.

"Rather than upsetting her, seeing the photos and reading the materials energized her and drove her to do the best job she could to tell the stories."

Ying-Ying Chang believes the antidepressants her daughter was taking heightened the suicidal tendencies she already harbored.

In September 2005, nearly a year after Iris Chang's death, her parents were invited to Nanjing for the unveiling of a bronze statue of their daughter at the city's Memorial Hall for the Victims of the Nanjing Mass-acre.

"I left China in 1949 with my parents when I was 9 and didn't return to Nanjing until 2005," Ying-Ying Chang said.

"We told our history to Iris, who then, through her work and her book, brought us back to where we had come from."

Since then the couple, who have set up the Iris Chang Memorial Fund in the US, have visited China seven times.

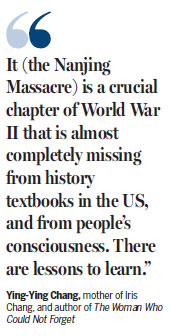

"We sponsor US high school teachers to travel here and learn about the Nanjing Massacre," Ying-Ying Chang said. "It's a crucial chapter of World War II that is almost completely missing from history textbooks in the US, and from people's consciousness. There are less-ons to learn."

Toward the end of her book, Iris Chang wrote, "Japan's behavior during World War II was less a product of dangerous people than of a dangerous government, in a vulnerable culture, in dangerous times, able to sell dangerous rationalizations to those whose human instincts told them otherwise."

Every time Iris Chang's parents visit Nanjing, Yang accompanies them.

"For a very long time in China, discussion of the Nanjing Massacre was not particularly encouraged, partly because of the shame involved," Yang said. "Today, another type of shame, one that Iris instilled in me, propels me forward in my research into the massacre."

In 2007, Yang translated The Rape of Nanking into Chinese. He said he will never forget the scene of the young author before the memorial stone, the setting sun lighting up the stele and illuminating her features. It reminds him of Sunrise, a poem Iris Chang wrote for her high school magazine.

"Rosy luminance appears

Over the edge of the earth

Banishing all the darkness

To reveal a new day's birth ..."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 12/14/2015 page6)

Historical photos reveal how Japan celebrated Nanjing invasion

Historical photos reveal how Japan celebrated Nanjing invasion

How firemen put out oil tanker blaze within two hours

How firemen put out oil tanker blaze within two hours

Wuzhen gets smart with Second World Internet Conference

Wuzhen gets smart with Second World Internet Conference

World's 4th largest lake Aral Sea shrinking

World's 4th largest lake Aral Sea shrinking

Nobel Prize 'to spur TCM development'

Nobel Prize 'to spur TCM development'

US returns 22 recovered Chinese artifacts

US returns 22 recovered Chinese artifacts

Internet makes life in Wuzhen more convenient

Internet makes life in Wuzhen more convenient

Miss World contestants at Sanya orchid show

Miss World contestants at Sanya orchid show

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|