Demons, dragons and redemption

Updated: 2011-08-28 08:02

By Zhang Kun (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

The urn, a burial accessory to carry the spirit of the dead to Heaven, was found in the Zhou family sepulcher and is unique. No similar piece has been found to date. Provided to China Daily |

Behind every museum piece is an interesting tale from the past. Zhang Kun finds out why an ancient ceramic piece from the fourth century set the benchmark for future finds, and why it is often mentioned in tandem with a prodigal son of Zhou.

The most precious piece of china in the Nanjing Museum is a squat, muddy-looking urn shaped like a toothy beast with spindly limbs and a tiny ball between tongue and teeth. It is also a unique piece, one of a kind.

(A copy brought to the museum a few years ago was a fake, experts say, although the man who brought it claimed to have seen it excavated.)

|

Experts also say the beastie urn dates from the early fourth century, around AD 302, and is a classic example of a ceramic production method that was widely used right up to the ninth century.

"The piece is an original design of high artistic level," says Huo Hua, an expert on Chinese ceramics in Nanjing Museum, Jiangsu province.

The body is that of a mythical beast with protruding eyes, flaring nostrils, upturned palms and hind feet, with clearly defined digits.

It stands 27.9 centimeters tall and is depicted with wings and a stylized beard.

"These are probably influences from Western Asia," Huo says. "Many animal images of the period were winged - including goats and oxen."

The glaze is a faded grayish green, similar to celadon, and its speckled color is probably the result of uneven exposure to high-temperatures during the baking.

According to Huo, green glaze appeared very early in China's ceramic history. Where there is more mineral content, the result is a darker color. When there is less mineral content, the result is a white glaze.

This urn in the Nanjing Museum was unearthed in the Zhou family tomb in Yixing, Jiangsu province in 1976.

"At grave sites, you can expect to unearth the most well-kept antiques and valuable treasures, while in ancient ruins, most of what you find are broken. To archaeologists like us, the ruins are mysteries to be solved. There is a lot of fun piecing together scattered pieces of information into a whole picture about ancient society and life," she says.

Documents found in the grave indicated that the urn with the winged creature was made in AD 302. This is one of the earliest antique ceramic pieces in China so clearly documented, so it is often used as an age standard when authenticating china from the Jin Dynasty (AD 265-420).

Vessels of similar sizes and style are often found in tombs of that age. They are placed near the deceased and archeologists learned that, these ancient people believed the vessels could transport the souls of the dead to Heaven.

Many of these early celadon pieces are getting popular on the auction market, prompting the appearance of more and more fakes and copies.

That is the reason why Huo often tells collectors to "buy antiques for enjoyment rather than serious investment."

The Nanjing Museum celadon also has an interesting tale attached.

|

Zhou Fang (AD 200-267) was a local official, and his son Zhou Chu (AD 238-299) was more known for his early youthful indulgence and later penitence and achievement.

The elder Zhou served in the court of the Kingdom of Wu during the Three Kingdom period (AD 220-280). In AD 228, he pretended to surrender to the Kingdom of Wei, and when an official of Wei doubted his sincerity, he immediately cut off his hair to show his commitment. In those days, hair in China was considered a sacred gift from one's parents and sacrosanct. It was not to be lightly cut and given away.

Having gained its trust, Zhou then lured the Wei army into a losing battle and later established a reputation as a governor known for his justice.

Folklore has it that his son, Zhou Chu was a violent and belligerent young man condemned as "a demon, just like the evil dragon in the river and the white-headed tiger in the mountains". Local villagers thought he was the most ferocious of the "three demons", and someone suggested they get rid of him by encouraging him to kill the other two scourges.

Zhou junior took the bait and jumped into the river, fighting against the dragon, swimming miles down the river for several days. People thought he was dead, and started to celebrate.

When he had successfully slaughtered the dragon and returned, he overheard what the people really thought of him, and in his shame, decided to mend his ways.

He was worried that it was too late, but Lu Yun, a famous intellectual of the day, told him that "ancient masters believed that if one learns about truth and righteousness, one would rest in peace even if one dies in the evening. Once you are determined to be good, honor will come naturally to your name."

Things turned out just as Lu said it would be.

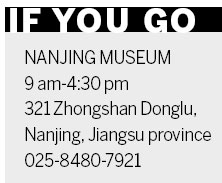

You can contact the writer at zhangkun@chinadaily.com.cn.