Profiles of a changing China

Updated: 2012-09-28 10:59

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

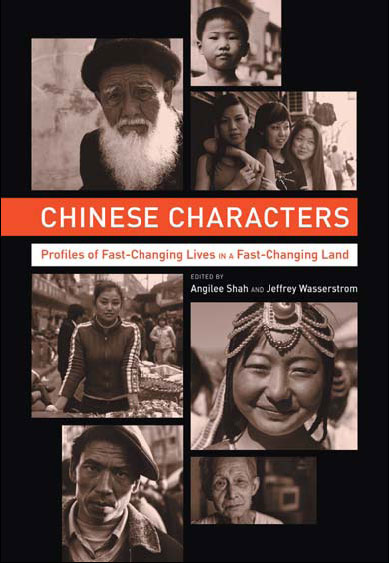

Chinese Characters features diverse stories of "regular people with regular problems," one of the book's co-editors says. Provided to China Daily |

In an essay about Tibetan youth, featured in Chinese Characters: Profiles of Fast-Changing Lives in a Fast-Changing Land, a young man faces a deep crisis.

Western readers, accustomed to information about Tibet in the context of political strife and upheaval, may be surprised to discover that this man's catastrophe is rather humdrum: romantic heartbreak.

"There are a lot of misconceptions and broad-stroke statements made about China today, and what China wants and does," Shah told China Daily. "We put this book together in hopes of presenting regular people with regular problems, who are simply living their lives against a changing backdrop."

Chinese Characters features 15 essays written by journalists and academics, all of whom have spent significant time in China. Contributors include Oracle Bones author Peter Hessler, New Yorker contributor Evan Osnos, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ian Johnson and Leslie Chang, author of Factory Girls.

Their profile subjects span both lifestyle and background: a "floating" migrant worker who ponders, between various jobs, China's national obsession with wealth; a Buddhist monk whose migration to the US helped preserve the religion during China's anti-religious periods; a young man intent on popularizing the electric guitar; and an artist who paints American landscapes she'll likely never see.

They all represent China, and not always the way Western audiences have come to expect.

"The main [misconception] that this book seeks to challenge is the idea that you can generalize about how 'the Chinese people' feel about any issue," said co-editor Wasserstrom, who is chair of the history department at the University of California, Irvine. "Too often, foreign commentators and the Chinese government alike fall into the pattern of making pronouncements about 'the Chinese people,' as if it were an undifferentiated mass rather than an incredibly diverse collection of individuals."

Wasserstrom is also co-founder of the popular China Beat blog and an associate fellow at the Asia Society. Shah is a consulting editor to the Journal of Asian Studies and a freelance journalist.

The book is the result of a conversation between Wasserstrom and Peter Hessler several years ago when the two discussed the lack of an anthology of short pieces by talented China-focused writers, Wasserstrom said.

The collection is organized around five themes: Doubters and Believers; Past and Present; Hustlers and Entrepreneurs; Rebels and Reformers; and Teachers and Pupils.

In the book's introduction, Wasserstrom writes: "The chapters that follow remind us that China is now a place where identities can be taken on and shed with surprising ease, in ways that can be exciting or exhausting, traumatic or confusing, or, in many cases, all of those things at once.

"The China revealed by the characters in this volume is a place where lives can suddenly be turned inside-out as opportunities are seized or squandered, and change is by turns liberating and unsettling." The essays "all beg a common question of their characters: 'Who will they be next?'"

What sets the collection apart from the raft of China books in recent years is that each chapter not only presents a new subject, but each story is written by a different author with a distinctive style of storytelling, Wasserstrom said.

"I think the sheer range of contributors is exciting," he said.

In addition to the book's American authors, writers also come from Europe, Canada, China and India.

"How often do American readers get an Indian perspective on China?" Shah said. "We wanted to present new perspectives from people with deep, local connections to the place. We didn't want people who were focused on high-level politics or policy; we wanted people with an ear to the ground."

The book does not attempt to "shape the world," Shah said. "But I do have a broader sense that storytelling is incredibly important in how people's world views are shaped. We wanted to give the writers the space to tell amazing stories."

"Western news about China is so often dominated by economics and politics," she said. "I know a lot of journalists who work in China, and I know how earnestly they try to portray China fairly, but there often just isn't enough space to tell these longer stories.

"People in the US ask me a lot of questions about China, and they're worried about its influence. I think that has a lot more to do with American politics, because China is a convenient rhetorical tool. Part of doing this book was about getting a personal relationship going with our readers and people in China."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|