Student documents lives of peers in US

Updated: 2012-11-02 11:36

By Wang Bowen and Joseph Boris (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

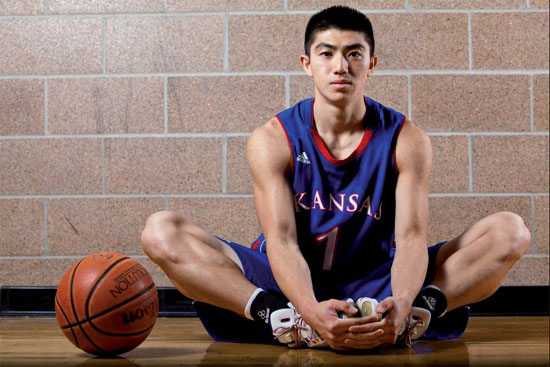

Saiyuan Bian, who tried out for the University of Kansas men's basketball team, is one of about 200 Chinese students in the US inverviewed by film major Liu Hainan. Provided to China Daily |

|

Liu Hainan records a calligraphy class given by Wu Qian, a Chinese student from New York University who is a volunteer teacher at Xi Fang temple, a Buddhist church-school in Brooklyn. Wang Bowen / For China Daily |

Liu Hainan wasn't sure what the experience of studying in the United States would ultimately mean, and he wondered if others like him shared that uncertainty.

To find out, the freshman documentary-film major at the San Francisco Art Institute picked up his camera and started shooting. That was two years ago.

"Studying abroad is like a fortress besieged. This documentary will be a call from us, and a gift to people outside the fortress," Liu wrote in a November 2010 blog entry on Renren, a Chinese social-networking site akin to Facebook. He asked his fellow Chinese students in the US to tell him their stories, and he would visit to capture their thoughts on tape.

The response was overwhelming, he said.

On a cold night before Halloween in 2010, Liu conducted his first interview, with a journalism major at New York City's School of Visual Arts. In the two years since then, he has traveled to universities and colleges in Michigan, Rhode Island, Kansas, New Jersey, Washington, Massachusetts and other states. He would stay at one school for a week or two, sleeping on his subjects' couches, sharing meals, going to their classes, taping their activities, and interviewing the students and those around them.

At first, Liu left his taping for the weekends. But he soon realized the project required more of his time. By the end of January 2011, he had decided to take a year off from school so he could devote himself to the movie.

To date, Liu has interviewed some 200 students, of whom 20 are focal points of the film. The 500 hours of footage he shot are mostly intensive, extensive firsthand accounts of the experience of studying abroad. Liu made friends with some of his interviewees, affording him an intimate look at their stories.

He has posted regular updates on his blog, keeping Renren followers apprised of the film's progress. He edited the first trailer from the copious footage and uploaded it to China's popular Youku video-sharing site, where it has been viewed more than 363,000 times.

The popularity shifted from the Internet to Phoenix Television, a Hong Kong-based satellite channel that aired the trailer just days after it was posted on Youku.

"I want to record our lives while we're still young," Liu intones in Chinese in the trailer.

After his first year in the US, he felt the urge to chronicle his life so that someday he could relive the experience and remember how it shaped his future.

The son of a professional, middle-income couple in Beijing, Liu has used money his parents set aside for his undergraduate studies to finance the making of his film. He asked that his parents' occupations not be published.

The documentary, he said, "captures the shared desire of many people to leave their current lives and glance into others' lives. I would like to see that happen, too, by making this film."

The trailer seemed to whet the appetites of Liu's online audience. Several posters said they, as Chinese students abroad, had been hoping for a movie like this.

The number of Chinese studying abroad has reached almost 2.5 million, making China the world's biggest source of international students, according to this year's Blue Book of Global Talent, a social-science research volume published in China.

At US higher-education institutions, enrollment by Chinese students rose to nearly 158,000, about 22 percent of the total international-student body, according to Open Doors, published annually by the Institute of International Education with the US State Department.

Liu shared his own experience of encountering the large number of his peers preparing for study overseas.

A year ago, he was invited to tape an orientation meeting at Michigan State University's satellite office in Beijing. Liu recalled being stunned at the number of students and parents crowded in the lobby for the event. Michigan State in 2011 was expecting enrollment of over 3,000 Chinese undergraduates, just over half of all its international students, according to the university.

The familiarity that comes from arrangements like Michigan State's bolsters Liu's impression that, for many young Chinese, overseas study has become almost mundane.

"It's no longer like studying abroad, just moving to a place that happens to be in a different time zone," he said.

Through his project, Liu has met impressive students who aspire to, or have since graduation, become entrepreneurs, actors and architects. He listened to their stories as he taped, thinking constantly about how to present their stories with visual impact.

"In the documentary, I don't want to show how hard Chinese are striving here or how 'ashamed' the second-generation rich should be, but to present their lives as they are, as a proud and optimistic witness," the young filmmaker said.

In Kansas City, Kansas, Liu met Saiyuan Bian, whose ambition is to play in the NBA. Born to a working-class couple and raised by one parent, he has been chasing his basketball dreams with his father's support.

He didn't go to a specialized school for sports or receive any formal training, but Bian makes up for that with a dogged work ethic.

He was playing on a youth team in Shaanxi when God Shammgod, an American former professional basketball player, praised Bian for his defensive skills on the court and advised that he try to play in the US.

In 2008 he was admitted to Menlo College, a small school in Northern California, partly on the strength of his basketball abilities (though without a scholarship).

To boost his shot at the NBA, he transferred to the University of Kansas, a powerhouse in men's college basketball with 12 US national championships to its credit. Bian didn't make the Jayhawks team, at least forestalling his entry into the NBA, where Asian players remain a rarity.

He has been trying out on different semiprofessional teams for the past four years, hoping to make the cut, but it hasn't been easy.

Without a personal coach, Saiyuan was a training partner for some players on the Menlo College's women's team to gain insights into collegiate basketball.

In California, where life without a car can be all but impossible, he spent $1,200 on one with broken windshields and mirrors. Then there's the strain of loneliness and the pressure to succeed.

Now, Bian is taking a semester off from the University of Kansas to prepare for a tryout in the NBA's Development League.

After nearly two years of filming, Bian and Liu have become close friends. The latter has had difficulty in making his film and gets depressed sometimes. "But every time I think of him, still hanging in there, I feel encouraged," Liu said.

Mu Chen graduated from the University of Virginia in 2010 and has been working as an investment analyst in the Bank of Tokyo's office in New York.

On his first day at work, Chen drew the unwanted attention of his boss for wearing a rumpled shirt. Embarrassed, he bolted to a nearby store and bought a new shirt. Chen quickly drew his new boss' approval and, at year's end, even got a bonus.

He points to his receding hairline as evidence of his hard work but still finds time for online lectures about China by professors from Harvard to help prepare him for possibly starting a business in his native country.

"I'm amazed by his ambition," Liu said.

Many Chinese graduates share that kind of drive but are at a crossroads in considering whether to stay in the US or return home for work.

"Timing is very important," Liu said, having discussed that question with many of his interviewees.

Some want to remain in order to recoup their parents' investment in their education or to realize the prestige of having "made it" in the US. Still others just desire to live in the US while some want to accumulate work experience and wealth so they can go back to China with a head start on prosperity.

For others, a return home upon graduation is imperative because they feel the urge to take part in China's development.

Whether they stay or go, Liu believes China as a country benefits. Chinese people, he reckons, still feel attached to their motherland wherever they are.

"If people do not go out, who can bring advanced technology and progressive thinking back to China?" he said.

Among the students he interviewed, Liu also met some from China's super-wealthy families, sometimes called the "rich second generation".

Though portrayals of this group in Chinese media tend to be negative, Liu said he has found that among their ranks studying in the US, many of the spoiled-brat stereotypes don't fit.

To be sure, some students from rich families flaunt their wealth with Lamborghinis and Ferraris parked outside the houses they're renting - or have even bought - near campuses.

Most, however, aren't ostentatious and are quite at ease hanging out with their middle-class peers, Liu said. Some even try to conceal their identities as sons and daughters of privilege.

"They are unfairly demonized," said Liu.

A finance student at Georgia Tech in Atlanta who is the son of rich parents makes over $10,000 a year as a go-between for Chinese who want to buy skin-care products and cosmetics from the US.

"He is ashamed of depending on his wealthy family," said Liu.

Liu said he didn't want his film to emphasize the material advantages enjoyed by such students, lest they be misunderstood or unfairly held up to scorn. In his view, "wealth can have a positive influence on people. It makes people more confident and enables them to achieve things."

After another three months of shooting, Liu got down to sifting through and editing his footage.

"I want to cut it myself rather than depending on some professionals because this is my film, and they probably wouldn't completely understand my plan," he explained.

Having set high standards for his project, Liu admits the film is now "halfway done". Once it's completed, his goal will be to get the movie screened at a few independent cinemas and then make it available for free online.

"It all depends on the public reaction to the movie," he said.

The self-imposed demands, while mostly pushing him forward, have on occasion left him tired and on the verge of quitting.

"Documenting and filming can be very hard and exhausting - couch-surfing, staying up late, driving 600 miles a day and waiting. Sometimes I felt tired and wanted to give up," Liu said with a smile.

But when he turns on his computer, where all his footage is stored, to view his work-in-progress, Liu feels like he's witnessing history of a very personal sort.

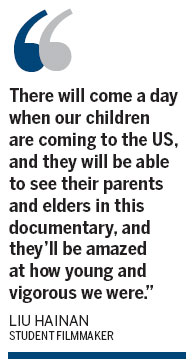

"There will come a day when our children are coming to the US, and they will be able to see their parents and elders in this documentary, and they'll be amazed at how young and vigorous we were," he said wistfully.

The swirl of TOEFL tests, application deadlines and, inevitably, culture shock can overwhelm students sometimes.

While busy with academics and increasingly proficient in English, many aren't sure where they are headed, according to Liu's experience

"It's difficult to figure out because it's not simple math," he said.

Looking back, the filmmaker said he set out to ascertain the importance of studying abroad but came away feeling that the answer isn't as important as he initially thought.

"Life is like watching a movie in a theater: You can't pause or play it back; the only thing you can do is to see it happen."

Contact the writers at josephboris@chinadailyusa.com and wang.bw.irene@gmail.com

|

Minzhe Zou answers a question in a statistics class at Orono High School in Maine. He is one of many Chinese whose families send their children to the United States for education, most commonly at the college or university level. Robert Bukaty / For China Daily |

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|