Reclaiming a heritage lost, stolen or sold

Updated: 2014-02-21 13:24

By Chris Davis (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

At least 17 million Chinese cultural relics are scattered around the globe, with 1 million of them art objects in 200 different museums in 47 countries, not to mention private collections. When and if they will be returned is an unanswered - and avoided - question, China Daily's Chris Davis reports from New York

Leading his biggest ever trade mission to China last December, British Prime Minister David Cameron set up a microblogging account on China's social network Sina Weibo - the Chinese version of Twitter - to take questions from anyone wanting to sound off during his visit. After five days, the page had 260,000 followers and, according to the London Daily Mail newspaper, one of the most repeated and persistent questions was initially posted by the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges, a highly regarded Chinese think tank led by former vice-premier Zeng Peiyan.

The question was: "When will Britain return the illegally plundered artifacts?"

The items in question are 23,000 artistic, cultural, archaeological and religious artifacts sitting in the British Museum that allegedly were plundered by the British army during the Second Opium War in the 19th century.

The centerpiece of that military action - the 1860 destruction of the magnificent Yuanmingyuan, or Old Summer Palace, which itself had museums within museums - has been well documented as a punishment by British and French troops for mistreatment of prisoners.

It was a self-ordained "legal pillage" and so-called "prize agents" were appointed to police the looting to see that no one side of the expeditionary force got more than any other. But greed took over and the system reportedly degenerated into a frenzied free for all. As one eye-witness put it:

French infantry, Englishmen, unmounted cavalry, artillery men, Queens dragoons, Sikhs, Arabs, Chinese coolies this ant-heap of men of every color, of every race, this entanglement of individuals from every nation on the earth, swarm on this mound of riches, hurrahing in all the languages of the globe while each carried off something we did not simply pillage; we wasted and squandered my heart bled on seeing, for instance, the space which separated the palace from our camp covered with silks and precious fabrics trampled in the mud-goods worth twenty millions engraved ivories, thrown into the trodden paths over which rolled the wheels of wagons

As Sheila Melvin writes in the Asia Society's ChinaFile: "The British were said to be better looters than the French, working together and systematically selecting valuables that they auctioned off right outside the palace gates (and which British auction houses auction off to this day)."

UNESCO numbers

UNESCO estimates that at least 17 million Chinese cultural relics are scattered all over the world, far more than are housed in China's own museums.

Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, a professor of history at Pace University who specializes in cultural-heritage management, said that of those 17 million, 1 million are art objects now in 200 different museums in 47 countries, not to mention private collections.

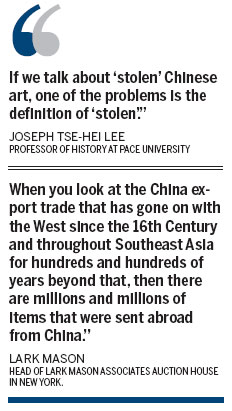

"So basically we're talking about huge numbers of Chinese art," Lee said, adding that when you look closely at the history of some of these items, most of them were taken from China since the late 19th century, but it's not that simple. "If we talk about 'stolen' Chinese art, one of the problems is the definition of 'stolen'."

"Most of the time we tend to focus on those arts taken by foreign invaders in the late 19th, like just after the Boxer Rebellion," Lee said. "But after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty (in 1911), we had huge numbers of Chinese arts being taken away from the old Imperial Palace by officials, and they were put on the market in the 1910s and 1920s."

Lee said it was also known that a huge amount of art was taken by the Red Guard during China's "cultural revolution" (1966-76) as well, "and those items are in the open market and also on the black market, either in China or in Hong Kong".

As a good example, Lee mentioned a Shanghai historian who told him that most of the collection in the municipal museum in Shanghai came from three major local collector families and most of the items had been confiscated by the state after 1949.

More recently, there is yet a fourth group of cultural relics that have been pillaged: those ransacked from areas that experienced major development projects, the most well-known being the Three Gorges Dam, which led to what Archaeology Magazine in 1998 called "an unprecedented rash of looting" in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River.

The dam - the largest hydroelectric project ever undertaken - submerged 13 cities, 140 towns, more than 1,600 villages and 300 factories, relocating 1.5 million people, not to mention an untold number of cultural and archaeological treasures. The government initially allocated $250 million for the "race" to excavate and preserve cultural heritage items; the figure was reduced to $37.5 million and eventually tied up in bureaucratic indecision, with only trickles allocated, according to the Archaeology magazine.

Pillaging rampant

Pillaging filled the void preservation efforts left behind. Looters, flush with money from their sales, equipped themselves with high-tech prospecting equipment. Burial grounds holding thousands of tombs dating from 206 BC to 1644 AD were dynamited for the excavations and peasants scavenging artifacts overran the sites.

Not unlike the Egyptians, the ancient Chinese believed the afterlife was a kind of parallel universe where people lived in much the same way as they lived their daily lives and they created and were buried with models of the things they would need - food, furniture, servants, animals -as well as treasured possessions such as bronze ritual vessels and even silk. This was booty looters were after.

Lark Mason, head of Lark Mason Associates auction house in New York and a frequent expert appraiser of Chinese art on PBS's Antique Roadshow, is skeptical of the 17 million figure. He said that a lot of those items could be classified as material that was purposely exported from China and made for a foreign market.

"When you look at the China export trade that has gone on with the West since the 16th Century and throughout Southeast Asia for hundreds and hundreds of years beyond that, then there are millions and millions of items that were sent abroad from China," Mason explained.

Limit the count to just those objects that were created in China as burial wares - from an early period to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), for instance - and were exported after being buried and never intended for export, he said, "then I think you're looking at a much, much smaller number".

At the International Asian Art Fair in New York in the spring of 1998, a four-foot-tall bronze candelabrum dating to the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) sold for $2.5 million and was believed to be illegally excavated from the city of Baidicheng. The piece was extremely rare, there being only two others of its kind in all of China. NYU art historian Elizabeth Childs-Johnson called it "an exceptional work of art" of national importance and if indeed it had been stolen by grave robbers, "China's loss of this piece is a travesty". Yu Weichao, director of conservation of cultural relics in the Three Gorges area at the time, promised to look into the case.

Lee called the failed effort to deal with the Three Gorges excavations "a typical example of how things are done in China".

"If you look at the Chinese government's track record," Lee explained, "they institute a number of good laws on the protection of cultural heritage in 1982 and they rewrite that law in 1988 and again in 1991. Those laws make it very clear that it is absolutely illegal to steal and smuggle Chinese arts outside of the country. In some cases people were executed by the state for doing that.

"The main problem is the enforcement of some of these policies at the local level," Lee said.

Without naming any names, Lee said one company's CEO in China who worked for a major State-owned enterprise told him it was common practice for them to use the company budget to buy some art - old paintings or antiques - to decorate their offices and after they finish their term, they would just take the cultural items as their personal property.

Mason said that the demand for a lot of ancient Chinese tomb pottery and burial material has "largely subsided" among collectors, "particularly items that were illegally exported and taken out of China", for three main reasons: the widely publicized information about the illegality of the material; the proliferation of fakes and items that are nearly fake - meaning authentically ancient fragments that are reassembled into new objects; and the memorandum of understanding recently renewed between the US and China that makes it illegal to import a lengthy laundry list of items from China, whose own law is roughly that nothing older than 100 years can leave.

"These three things have conspired to erode the value, especially at the lower end of the market," items, he explained, that 30 years ago were considered rare and unusual and fetched astronomical prices but today, as tomb wares are more common, sell for under $5,000.

'Big prizes'

Collectors now are after the really best examples from legitimate sources, well-established dealers with strong reputations and auction houses that sell items that have a strong provenance from being previously sold at auction or sold through a reputable dealer.

"All of the 'big prizes' today are items that have a history of prior ownership," Mason said. "It's almost essential that items have some sort of a provenance - authenticated and sold in the open market - so there's not going to be any kind of issues with the disposition in the future.

"For the collector, the Holy Grail is to find an object that is rare, that is beautiful, that is in good condition and that also has a strong provenance," Mason said. "It's unusual to find something that possesses all of those features."

As for the British Museum's collection and the unofficial call for it all to be returned, the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport said, "Questions concerning Chinese items in museum collections are for the trustees or governing authorities of those collections to respond to and the government does not intervene."

The British Museum's stance is the same as it is with other artifacts - such as the Elgin Marbles removed from the Parthenon in Athens in 1801 - arguing that they are objects of world heritage and more accessible to more viewers by being in London.

"There is clearly a serious misunderstanding," a spokesman for the British Museum said. "There are around 23,000 objects in the museum's Chinese collection as a whole, the overwhelming majority of them peacefully traded or collected, many indeed made for export. Very few objects entered the collection in the context of, even less as a result of, [the Opium Wars]."

Earlier this month, a Norwegian museum announced that it would return seven marble columns taken from the Old Summer Palace 150 years ago, in a three-way deal between the Kode Art Museum in Bergen, Peking University (where they will reside) and wealthy Chinese tycoon Huang Nubo, who will donate $1.63 million to the museum.

Huang said he visited the museum last year. "The moment I saw the columns, my eyes teared up," he said. "After all, the lost relics from Yuanmingyuan represent an indelible history for all Chinese. I told the museum staff the relics should not be on show and they were sympathetic to my feelings."

The Norwegian museum got 2,500 Chinese artifacts from Norwegian calvary officer Johan W. N. Munthe in the early 20th Century - who had obtained them from sources unspecified, among the cache were 21 of the columns, which were crafted in a Greco-Roman style to decorate a Western section of the garden.

"The museum is in possession of 21 columns and has for decades only showed seven," said former museum director Erland G. Hoyersten. "So transferring seven of the 21 columns to China will not be a loss to the museum."

Another return

Another high-profile return occurred in June 2013 when Qing Dynasty bronze heads of a rabbit and a rat - part of an elaborate fountain-clock that spewed water through the mouths of 12 Chinese zodiac animal heads every two hours - were returned to China. French billionaire Francoise-Henri Pinault, chairman and CEO of Kering, the luxury fashion conglomerate that owns Christie's auction house, bought them and donated them to the National Museum of China.

Five other of the 12 heads have been recovered by China - the horse, pig, monkey, tiger and cow are on display. Where the remaining five are remains a mystery.

"Right now the Chinese government and all of the foreign museums have a very good record and inventory of those arts being sold to the museums by foreigners starting from the late 19th and early 20th century," Lee said. "Those items could be easily identified by the governments on both sides."

Lee said that one of the most controversial collections was Buddhist art from Dunhuang in western China, which again was removed from China at the turn of the 20th Century. "I think the British can argue that at the time, there were no clear legal channels regarding the return or ownership of those materials", Lee said.

"When you think about China's growing sense of confidence about the country's transformation," Lee said, "the new Chinese leaders beginning to reposition themselves as the guardians of Chinese civilization and culture, I think that is actually a good sign if they recognize the importance of cultural heritage, they recognize the need to protect it and also to preserve it. Not just for the Chinese but also for the global audience as well.

"Chinese leaders now talk more about the revival of Chinese civilization, revival of the Chinese culture, revival of the Chinese nation. Heritage management is also related to the issue of China's soft power as well. If you talk about Chinese art, it is probably the only traditional heritage that is extremely well known outside China.

"So I think if the government can actually do something to protect and preserve it - and even reclaim some of the stolen ones - that would actually promote the Chinese voice on the global cultural front. It would also recast China as a stabilizing force in the international cultural landscape," Lee said.

"Also in the short term I think that kind of approach will also help Beijing's policy of reunification by using these arts to project a common identity among all Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and elsewhere."

Contact the writer at chrisdavis@chinadailyusa.com

|

After spending 150 years abroad, Qing Dynasty bronze heads of a rat and rabbit - two of 12 zodiac fixtures that were part of a fountain-clock raided in the destruction of the Old Summer Palace during the Boxer Rebellion - are on exhibition at China National Museum in Beijing after they were recently returned to China. The pig, horse, monkey, tiger and cow have also been recovered. The snake, dragon, lamb, dog and chicken are still missing. Jin Wen / for China Daily |

(China Daily USA 02/21/2014 page20)

US warns of airline shoe-bomb threat

US warns of airline shoe-bomb threat

Beijing issues 1st yellow alert for smog

Beijing issues 1st yellow alert for smog

Beauty queen the latest victim in Venezuela unrest

Beauty queen the latest victim in Venezuela unrest

Italy court finalizes Berlusconi divorce

Italy court finalizes Berlusconi divorce

Neighbors keen to open trade corridor

Neighbors keen to open trade corridor

Beijing wants more cross-Straits contact

Beijing wants more cross-Straits contact

Spirit of adventure lives on in Antarctic

Spirit of adventure lives on in Antarctic

Prince Charles dances in traditional Saudi dress

Prince Charles dances in traditional Saudi dress

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China firmly opposes Obama-Dalai meeting

Americans view China 'most unfavorable'

US VP calls Ukrainian leader, warns of sanctions

Can Tencent crack US market?

Chinese can now cherry pick in US

Growth in emerging economies to decline: IMF

NYC Mayor caught breaking laws

IPhone makes gains in China

US Weekly

|

|