Scholars from and on China

Updated: 2014-02-28 11:07

By Chen Weihua (China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Cheng Li has become the first Chinese American to lead the Brookings Institution's John L. Thornton China Center, and Li is looking to expand the think tank's horizon with some of the top China experts in the US, Chen Weihua reports from Washington.

In 1985, when Cheng Li went from his hometown Shanghai to attend the University of California at Berkeley, he was keen to study literature.

The 29-year-old, however, did not realize that the East Asian studies program there had three different tracks, for literature, language and political economy. By mistake, he was enrolled in political economy and a transfer was not possible.

Under mentor Robert Scalapino, a noted political scientist on China, Li fell in love with his field of study and went on to Princeton University to pursue a doctorate in political science, this time by his own choice.

On Feb 21, the Brookings Institution, ranked the world's No 1 think tank for three consecutive years by the University of Pennsylvania's Global Go to Think-Tanks Report, named Li director of the John L. Thornton China Center, effective March 3.

This means that Li will be in charge of a team comprised of some of the top China experts in the United States, such as Jeffrey Bader, Kenneth Lieberthal, Richard Bush, Jonathan Pollack and David Dollar.

Bader and Lieberthal have respectively served in the White House as senior director for Asia and East Asia during the Obama and Clinton administrations, while Bush served as national intelligence officer for East Asia in the National Intelligence Council.

Pollack worked at the Rand Corp and the US Naval War College and Dollar was the World Bank's country director for China and Mongolia and later the US Treasury department's economic and financial emissary to China until last year.

"This is great a treasure and world-class team in China studies. I feel very humbled to work with them," Li, now widely regarded as one of the world's leading authorities on Chinese leadership, told China Daily in an interview.

Becoming an expert

Li credited his achievements to guidance he received from his mentors, the late Scalapino and A. Doak Barnett, the late leading scholar and US government adviser on China who recommended Li to be a fellow of the Washington-based Institute of Current World Affairs, which allowed him to work in China from 1993 to 1995.

Now a board trustee of the institute himself, Li described his two years in China as essential for his later achievements. The advanced academic training in the West and his intimate knowledge of his native land helped him in "rediscovering China," which was also the title of his first book, published in 1997.

Growing up in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Li, the youngest among seven siblings, did not go to the countryside like millions of Chinese youth to receive so-called re-education from the peasants because his elder brothers and sisters had already gone there. Instead, he attended a three-year vocational medical school and ended up being a physician at local hospitals in Shanghai for four years.

Compared with the older generation who left China before the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 and the younger generation born after the Cultural Revolution, Li believes the life and education experience of his generation has helped them understand today's China in a much more sophistical way.

He feels fortunate that he chose to focus his study on Chinese leadership and set up his own databank on Chinese elites.

Unlike the research based on abstract modeling or instinct done by some scholars, Li's databank, which now includes some 20,000 Chinese officials and other economic and cultural elites, enables him to analyze and speak with facts.

When Li wrote in the late 1980s and early 1990s about the rise of "technocrats" in the Chinese leadership, probably no one had used the term to describe Chinese government officials.

But to Li, the databank reflects clearly the trajectory of China's political elite. It was not a surprise to the world that later top Chinese leaders such as Jiang Zemin, Zhu Rongji, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, had an engineering background.

While his studies helped establish his reputation in academic circles, Li later noticed a dramatic shift in China's leadership: a decline of the technocrats. Only one of the current seven politburo members of the Standing Committee of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China - Yu Zhengsheng - has an engineering background.

The rise of technocrats has widely been believed to contribute to China's double-digit economic growth and dramatic infrastructure transformation. To Li, an increasingly diverse background of the political elite is important to China as the country faces not only economic challenges, but huge social and environmental problems.

Due to his unique expertise, Li, now a Chinese American, has been a sought after speaker in the past decade or so when the change in China's leadership drew huge attention in the US and around the world.

His next book, Chinese Politics in the Era of Collective Leadership, is expected to be finished this fall. It tells that China has recently undergone a major political transition from an era shaped by the arbitrary power of strong paramount leaders, first Mao Zedong and then Deng Xiaoping, to a new era of collective leadership. Consequently, China's political structure, the rules and norms that govern its elite politics, and its policy formation process are all undergoing profound changes.

Rising middle class

Besides delving into the Chinese leadership, Li was also probably the earliest to write about China's emerging middle class when no one thought about or used the term in China. His book Rediscovering China: Dynamics and Dilemmas of Reform about the Shanghai middle class was rejected a few times in 1997 by publishing houses.

"They don't believe a middle class exists in China, and they believe China only has a small group of rich people and the majority are poor people. But now everyone is talking about middle class," he said.

A McKinsey & Company report last June shows that the explosive growth of China's emerging middle class has brought sweeping economic change and social transformation, and it's not over yet.

By 2022, more than 75 percent of China's urban consumers will earn $9,000 to $34,000 a year, a middle class income range, according to McKinsey.

Li is also working on a new book about China's middle class. Now titled Middle Class Shanghai: Pioneering China's Global Integration, it will focus primarily on Chinese who returned to the country after studying abroad. The book, based on surveys done in Shanghai in 2009 and 2014 respectively, will tell the differences and change in values for those returnees and the homegrown middle class.

Chinese thinkers

As director of research at the John L. Thornton China Center for the past few years, Li has been a principal editor of the center's Chinese Thinkers Series, which introduced prominent Chinese thinkers to English-language readers. They include China in 2020 by economist Hu Angang; In the Name of Justice by He Weifang, a noted law professor at Peking University; and Democracy is a Good Thing, a book by Yu Keping, deputy chief of the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Yu's book sparked heated debate in China when it was released in 2006.

Li wrote a preface for all the books, and he said he feels fortunate that through doing so he made close contacts with China's prominent scholars.

He feels proud that China now boasts some of the top scholars, especially on the Chinese economy and society. On the other hand, he said he is concerned that academic restrictions in some areas - such as law and political science - have a negative impact on some scholars in China.

While more world-class scholars have surfaced in China, Li is also delighted to see the rise of many fellow Chinese scholars and researchers now working in the US, just like himself.

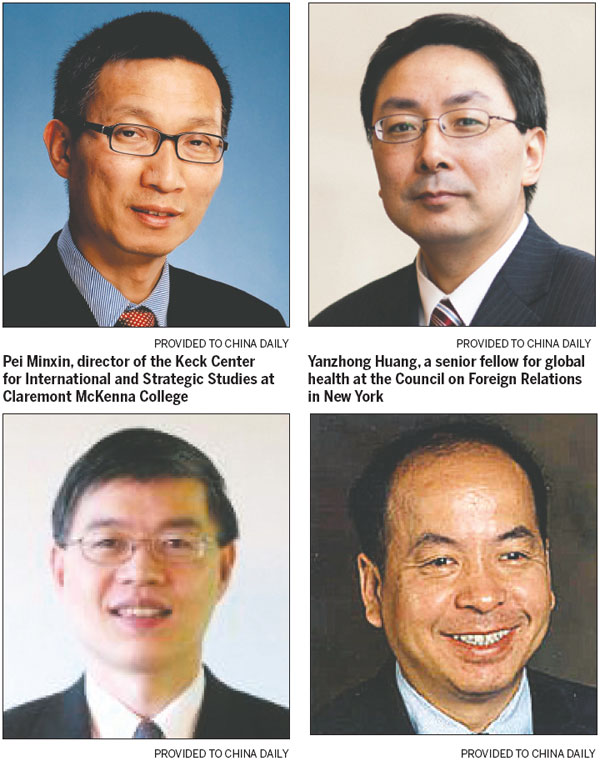

Though views often differ, Li mentioned how he appreciates Pei Minxin, now director of the Keck Center for International and Strategic Studies at Claremont McKenna College and former senior associate of the Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "His words were sharp, but he was often very insightful. It's so much better than those who know only flattery," said the 57-year-old.

Like Li and Pei, many other scholars coming to the US from the Chinese mainland in the past three decades have also become opinion leaders, such as Yawei Liu, director of the China program at Carter Center; Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago and Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. The list goes on.

Many of the scholars of Li's age came to the US in the 1980s when China just opened to the outside world. Their experience of the catastrophic Cultural Revolution is unimaginable to the younger generations. Meanwhile, these scholars are believed to not only inject fresh spirit into the study of China in the US, but also help connect the study of China within and outside of the country.

Li credits the rise of China for the achievements that he and his fellow Chinese scholars in the US have made.

"Without the more than three decades of reform and opening up, the social and economic transformation and China's growing status and influence on the world stage, there won't be such attention and interest in China in the West and there won't be such a Sinomania," he said.

Learning, leading

In Li's view, China has been changing so rapidly that every student of present-day China must challenge himself or herself. "You will feel disconnected if you don't go to China for two or three years and don't keep in touch with the reality there," said Li, who regardless of his Chinese background and knowledge, still travels eight or 10 times to China every year.

That is probably why when Max Baucus, the new US ambassador to China, was chided during his US Senate confirmation hearing last month for his lack of China knowledge, Li immediately came to his defense, arguing that Baucus is good at learning and listening.

Li, who had a conversation with Baucus not long ago, said such characteristics in a person are more precious than what he knew before, or even if he is an expert on China.

With his new post starting next Monday, Li is ready to lead his star-studded team of China experts at Brookings to expand the institute's horizon.

To Li, Brookings' own standing, the center's world-class team, its Beijing office and the vision and financial support from its chairman of the board, John L. Thornton, are a huge advantage. But China has been changing so rapidly, it requires think tanks to constantly monitor the change.

He said the center should have a global perspective, be able to grasp issues in a timely manner, provide policy analysis and be able to look into the future.

He wants the center to produce more positive impact, such as in facilitating exchanges between the two central governments and also governments at the local level.

"Brookings' convening power will enable its scholars to interact more with government departments and first-class scholars elsewhere," he said.

His Brookings China Center team is also ready to advise both Democratic and Republican candidates in the 2016 presidential election, as well as to those in Congress. Li joined the advisory team for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign in 2008 and later President Barack Obama's team after he defeated Clinton for the presidential nomination. The new team leader also has set his sights on the meeting of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of China in three years.

"Quality, independence and impact will guide the center, Li said, citing Brookings' motto.

An optimist

A frequent commentator in global media on issues regarding China or China-US relations, Li remains overall optimistic about those relations despite the often pessimism of other scholars in China and the US.

He said his optimism on China is based on China's most rapid development in history. "China's expanding middle class, growing economic status, people's changing mindset, entrepreneurship and their yearn for globalization and integration into the world, the state-of-the-art infrastructure and advances in science and technology have all created huge advantages for China," he said.

"I can give a long list," Li said.

To Li, China's rise may not look like a straight line, but he believes that no one, or even a burst of the current real estate bubble or a financial crisis, can halt its steps forward.

"It all depends on how the leaders can grasp the opportunities," he said.

The expert on Chinese leadership gives high marks to the first year of President Xi Jinping's leadership.

He talked positively of the vigorous anti-corruption campaign, the outcome of the trial of Bo Xilai, a former Politburo member and former Party chief in Chongqing, and most importantly, the comprehensive and deeper market reforms embraced at the Third Plenum of the 18th CPC Central Committee.

"They have done a lot of things in the first year to meet the high expectations and overcome the various challenges both at home and abroad," Li said.

"The new generation of leaders has made a good start, bringing constant changes and delightful surprises. This has also largely been the case for China in the past 25 years."

Contact the writer at chenweihua@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 02/28/2014 page19)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese firm acquires Texas oil, gas company

Chinese firm buys two new helicopters from US' Bell

Peace quest spurs defense push

Obama, Merkel discuss Ukraine crisis

US first lady to visit China

Obama releases budget request

China embraces market forces

Sino-Germany electronic trade surges

US Weekly

|

|