Grand designs

Updated: 2011-10-14 08:58

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

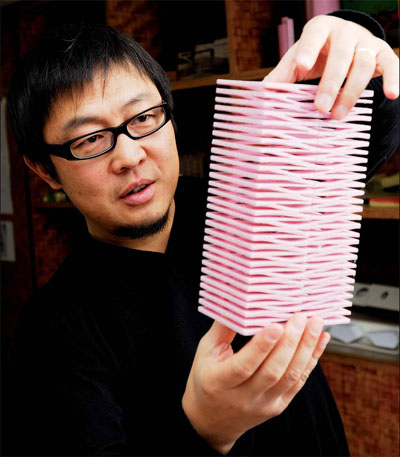

Top Chinese Architect leads elite school in southern california

Ma Qingyun accepted the job as dean of the University of Southern California's prestigious School of Architecture because he was weary of being his own boss.

His private Chinese firm MADA s.p.a.m. had grown to be highly successful, but he found himself repeating similar projects and felt restless.

"Architecture alone doesn't have the full ability to engage social and economic issues, and a lot of urban and environmental problems cannot be resolved purely through building," he says.

"I felt incapable of addressing some of these problems and I thought, 'What should I do to refresh my view of what's happening in the world and in China in order to find solutions?'"

As an entrepreneurial designer, his work was no longer critically evaluated or judged, he says, so when the university launched its search for a new dean in 2006, he jumped at the challenge.

"The architecture school at USC is at the crossroads of design intelligence and technology integration. Design has a large role in commanding or specifying the most advanced technology, and today it's really about sustainability, environmental sciences, and how these technology aspects are being integrated together to serve design intentions," he says.

"This is the tradition and core mission of the school, so what I'm doing there is in hopes of enhancing that tradition and putting it in a global context."

In 2008 Ma founded the American Academy, a graduate program through USC's School of Architecture that operates in China. The program immerses American students in the study of unique architectural and city planning problems in China.

Each year the program focuses on a specific topic that is relevant to Chinese architecture. For example, in the first year students studied "convergence in divergence".

"Because the speed of investment in China is so high, cities tend to grow into multiple dimensions and there is a coexistence of style and technology. A very chaotic urbanism exists in China but it's also managed and coordinated into a coherent energy. That's very rare in Western urbanism. It's a uniquely Chinese urban paradigm."

This year students are focused on the way robotic technology might revolutionize the building industry.

"Much of the Chinese population with cell phones today had never used phones at all previously. This technology leap saves energy, and it's the right time to discuss this in China because it is my hope that China doesn't repeat some of the same wasteful practices of the West. We can engage new technologies so much faster because we're still in an emerging state of design and architecture."

In addition to his position as dean, he continues to work with MADA s.p.a.m., primarily with local Chinese builders, but is also consciously staying global. The firm has worked in Vietnam and has entered competitions in France and the United States, among other countries. He also runs a wine-making business which was previously his hobby.

Running a private business is worlds apart from working at a university. Ma says one of the most inspiring parts of his work with USC is fund-raising.

"What's really noble about it is you don't sell anything, you present your mission to society, and donors invest in a great idea or vision," he says. "It's very gratifying to be in the business of convincing society of great ideas. That's really exciting for me."

Working as a dean is much more structured and disciplined than working in the private sector, but the payoff of molding students in the field is worth it, he says.

"We're dealing with formidable young minds who can be absolutely anything, and you're there to influence them."

Ma's family members are all in the clothing industry, trained in dealing with fabrics and garments. He says the reasons for his attending Tsinghua University were complicated.

"My father told me that clothing is your first layer of architecture and that always stuck with me," he says. "But the real reason I chose architecture was because I was really good at drawing."

After receiving a bachelor's degree from Tsinghua, he later attended graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania. He has taught architecture at Shenzhen University and Nanjing University in China, and Harvard, Pennsylvania and Columbia in the US.

There are huge differences between Chinese and American architecture education programs, he says.

In China the focus is typological, dividing buildings into categories based on their function.

Students work in apprenticeships, which are more teacher-focused and rarely allow for discussion or input. American architecture programs are inquiry based, tending to frame architecture and design as an ability to solve existing problems. The work is more hands-on.

"Fortunately I was exposed to both types of training. I understand each side of it, and I happen to be good at both. I can mobilize either side of my brain."

One major problem today is the question of sustainability. "My intention is to bring sustainability back to common sense, to engage through not purely technological approaches, but also design elegance. Ultimately it's about seeking equilibrium, balancing building physics and building aesthetics and great life in a building.

"It's not about what the West is going to teach China about architecture, but about what the Chinese philosophy of living can teach the world."

This balance is evident in the buildings he is most proud of having built: his house in Pasadena, where he lives with his wife and two sons, and the home for his father in their hometown village in the mountains outside Xi'an.

He built the house to honor his father, who traveled around the world and then retired to his roots.

His own home in Pasadena has a more alien style, because he moved to California with no roots at all.

"I never see any one place as home," he says. "Wherever I find a landing pad is where I'll stop. In a way, these homes represent mental opposites, the extremes of everything I do."

Ultimately, Ma does not seek to be defined as specifically a Chinese architect.

"I feel that particularly innovative architecture has no cultural limits. No matter what the style of a building in China is, or what it represents, as long as it's well made and can stand the test of time, it will qualify as good architecture."

(China Daily 10/14/2011 page20)