The Ashdown low-down on China

Updated: 2011-12-16 07:48

By David Bartram (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

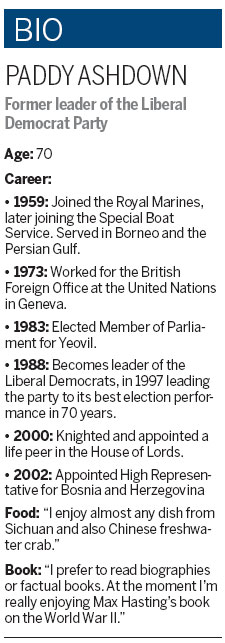

Paddy Ashdown says as China increasingly participates in international organizations, cooperation with the West will become easier. [Provided to China Daily] |

Former Liberal Democrat leader predicts more Chinese participation in int'l organizations

In politics, Paddy Ashdown, probably best known as the former leader of Britain's Liberal Democrat party, has always taken an internationalist perspective.

Having witnessed first hand several major conflicts during a military and political career spanning more than 50 years, Ashdown is convinced that China must play an active role in global affairs to ensure a peaceful transition toward a multi-polar world.

"There is a massive power shift taking place at the moment," Ashdown says. "The last time this happened was at the beginning of the 20th century, when power began to be passed over the Atlantic from Europe to the United States.

"Increasingly if we want to work together to get things done in the modern world, we are going to have to reach beyond the circle of Atlantic powers and build partnerships with others, and one of those will be China."

While Ashdown never made it into government while in charge of the Liberal Democrats, his international credentials are impressive. After stepping down as leader of the party, he became the United Nations High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2002. More recently he was linked to a similar UN role in Afghanistan, although not appointed.

|

|

He is no stranger to China. In the late 1960s he spent two and a half years living in Hong Kong learning Mandarin while on sabbatical from the Royal Marines.

"I became fascinated by Chinese and tried to teach myself the language." Despite being a gifted linguist who had already taught himself Malay, he soon realized that Mandarin would be an altogether more challenging proposition.

"I went to Chinese night school in between my military service. I was the only non-Chinese there, it was full of Cantonese and other Chinese speakers wanting to learn Mandarin. I soon discovered that I wouldn't be able to learn it in my spare time, so I went to Hong Kong to be a student on a full-time basis."

As Ashdown approached the end of his studies in 1969 and prepared to return to Britain, an unexpected encounter gave him the opportunity of some rather clandestine employment.

"One day, completely unannounced, I got a mysterious call from someone introducing himself as a member of the Hong Kong government. He said he was a member of the British Foreign Office, and that they were looking for people like me who could speak Chinese.

"I knew perfectly what was going on. This was not the Foreign Office proper. If this led anywhere it would end with my being asked to spy for my country."

The meeting led Ashdown into a job working for the British secret service MI6, although the reality of espionage proved more mundane than it sounds. One assignment in 1970 had him monitoring a group of journalists from the People's Daily visiting Northern Ireland.

"They wanted me to be part of the team that looked after the Chinese delegation, without letting them know that I could speak Chinese. My job would be to hang around, listen to what they said and report back.

"It seemed a pretty preposterous piece of espionage to me, but I went along with it. Though I heard and understood almost all they said, there was precisely nothing of any interest to anyone except themselves."

Ashdown left the service to focus on politics, becoming a Member of Parliament in 1983 and leader of the Liberal Democrats in 1988. With Ashdown at the helm the party became favored among Britain's Chinese community, in part because he lobbied strongly to give all British subjects in Hong Kong the right to move to Britain before the handover in 1997.

"We had a duty toward these people, but I also thought it would be in Britain's interests. Agreeing to allow 3.5 million Chinese to come and live in Britain was not a popular position, but in my mind there was no doubt that as a consequence there would have been a massive influx of capital and investment into Britain. You only have to look at Vancouver in Canada to see what could have happened."

Nowadays out of the spotlight of daily political life, Ashdown has turned his attention toward international affairs.

He sees China as a key player in the move toward greater international cooperation on issues as diverse as terrorism, financial regulation and trade.

"I think in the not too distant future it will be impossible to carry out interventions like the ones in Iraq and Afghanistan without it being cleared by the UN Security Council, of which China is a member.

"I think it is very possible that we may eventually find ourselves in partnership with the Chinese."

While he appreciates, and indeed has witnessed first hand, the cultural differences between China and the West, he sees no reason why these should preclude China playing an active role in world affairs.

"I'm not naive about China, I know how much we differ on many key issues. But if you look around the world and look at the way China is operating, on the whole she is operating in a highly responsible manner. China is showing a strong sensibility toward international law.

"China understands the international financial system, and is playing a role in helping the eurozone stabilize itself. They are starting to follow a much more constructive policy in Africa. There is real evidence that Beijing is understanding the complexities of the global situation."

Ashdown believes that as China increasingly participates in international organizations, cooperation with the West will become easier.

"The relationship between China and the West has always been characterized by the idea that both sides are inscrutable to the other. I don't believe that's true. I think it's much more of a myth than a reality. We soon discover there are universal human values and aspirations that each of these two communities share pretty unilaterally.

"The days when China genuinely saw itself as zhongguo, or the middle kingdom, around which the rest of the world circles, are long gone."