|

Large Medium Small |

If the name is anything to go by, Marcopolo Tam Siu-cheong is as much an adventurer as the 13th-century Venetian. Separated by almost 700 years, both men traveled in the name of discovery: For Marco Polo, it was for new lands; for Tam, an old map that recounts all the thrills of previous discoveries.

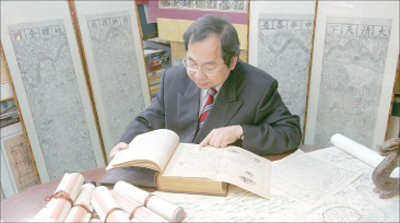

“You don’t stare at a map, as you may do to other collectibles — you read into it,” says Tam, sitting in his third-floor salesroom-office in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong, surrounded by piles of reproduction maps mounted on thick cupboard.

Ever since he started collecting old maps 30 years ago (150,000 maps and counting), Tam has had many epiphanies but none as big as the one that showed him a world other than his own. “It was in the late 1970s, when I was a software programmer,” he says. “I was sent to solve a computer problem in a small American town called Huntington, in the northeast of New York State, where I stayed for nearly three months.”

During that time, Tam befriended a local who later gave him an old Huntington City map as a farewell gift. “Soon after I got back to New York City, I realized the map was missing. Not only was it a map from 1860, it was a gift from a friend who I would probably never see again,” he says, “So I combed New York City for another copy.”

The hunt was fruitless but along the way, Tam came across numerous old New York City maps that had been printed around the same time. “I started buying those maps and — without even realizing it — building up my first collection,” he says.

Most purchases were the result of a lot of detective work, aided by one stroke of luck. “My job allowed me to travel extensively, for free, and I had probably made about 50 to 60 trips to Europe in the late 70s and early 80s,” he says. “Map collecting has a very long history in Europe, where every city and town, no matter what its size, had at least three or four antique bookstores that sold old maps.

“If you hung around long enough, you could count on meeting some local collectors who made such stores the hub of their activities.”

Their shared passion helped to create an instant rapport and Tam often found himself standing in front of fellow collectors’ hidden treasures.

“Believe me, they had gems,” he says. “Many of my most prized acquisitions can be traced back to those anonymous attic collections.”

Among them is China Illustrated, an old book Tam bought in Nottingham, England. It contains nearly 160 county and city maps.

“Every detail represents a persistent, sometimes desperate, and not always successful effort to see through the mystery that shrouded the Middle Kingdom,” he says.

“And bearing in mind that the last edition of the book was published in 1860, the year China was defeated in the Second Opium War, you really begin to see the roots of Western expansion, as imagination was replaced by knowledge, and admiration by aggression.”

For Tam, a self-titled “mapilgrim”, an old map is a road, a journey at the end of which the important lessons of history await.

In the 1980s, Tam was posted to Beijing, where he spent two years and added another 5,000 maps to his growing collection. Asked if he had visited Liulichang and Panjiayuan, the city’s two most famous antique markets-cum-treasure hunters’ haven, he says: “I grew up there.”

By then well known in influential circles, Tam received regular phone calls from antique map traders across the country. “If it sounded interesting, I would fly over there for a look,” he says. “Who knows? A major discovery may be an air ticket away.”

But how to ascertain an old map’s authenticity?

“A gut feeling is important,” says Tam. “You know subconsciously if a map looks and feels genuinely old.” Inimitable, fine engraving is often a big clue. Browning, holes, tears, water marks or even candle wax — all damage as they are — are also sought-after, tell-tale signs.

Tam nevertheless takes no risks with his purchases and has been served well by personal experience.

In November last year, Tam received a call “out of the blue” saying that Robert Mundell, the flamboyant Nobel Prize-winning economist and close friend of Premier Wen Jiabao, was interested in his maps. A few days later, Tam was busy de-cluttering his Causeway Bay office to prepare for the arrival of the “Father of the euro”.

“Mundell asked to see 19-century city maps of Guangzhou and Quanzhou, two places that were the earliest settlements for foreigners,” says Tam. “He was particularly interested in those showing city walls.” The two men talked for about three hours — two on maps, one on the international monetary system.

“He said nothing about his intention but my guess is that he was trying to garner ideas for a new monetary system that he might be designing,” says Tam. “What a walled city and a monetary system have in common is the inclusion and exclusion of resources.”

Tam believes maps have an ever-more important role to play.

In April 2005, four months after the devastating Asian Tsunami, he exhibited his satellite maps of the Indian Ocean at major railway stations in Hong Kong. In retrospect, the countless white vortexes that filled the surface of the ocean hours before the disaster struck seemed to be clear warning signs.

“The human tragedy would have been reduced if we had known how to read these maps,” he claims.

The call of maps has taken Tam around the globe but the day will come when he’ll stop to rest. “The saddest thing that could ever happen to a collector is to have his collection dissolved posthumously,” says the 58-year-old. “I will not let that happen.”

Tam has donated over 10,000 old maps to libraries, universities and other cultural institutions in Hong Kong. He is now in talks with the government of the United Arab Emirates to build the world’s largest map museum.