|

Large Medium Small |

“The area went into 40 years of disinvestment and now we’re trying to turn it around,” said Paul Dombrowski, director of planning and design for the Baltimore Development Corp, a nonprofit agency retained by the City of Baltimore for economic revitalization projects.

Tony Cheng, a restaurateur in nearby Washington, has bought at least a dozen properties in the area north of Baltimore’s Penn Station, which services Amtrak and MARC commuter train passengers to Washington. Growing a thriving Chinatown in Baltimore is part of Cheng’s dream, and he is an active force behind the planning. The area, called Charles North, already has an art scene emerging, and Cheng jumped at the opportunity to see his vision fulfilled.

Cheng began buying properties in 2006 and shared his ideas with the Baltimore Development Corp, which has encouraged more private investment of the North Charles area. But rather than turn it into a tourist site, as other Chinatowns around the country have become, Cheng wanted to blend Chinese restaurants and Chinese retail shops with non-Chinese businesses and residential housing for young professionals.

“This is more of a genuine community-based kind of thing he’s after,” Dombrowski said.

With China being the biggest new player on the economic world market, Cheng also believes Baltimore will be a perfect place to establish “direct contact, where there could be available opportunity for people to purchase or order Chinese goods directly from manufacturers or distributors,” said Cheng’s attorney, Dennis McCoy. Cheng was traveling overseas at the time and could not be reached for comment.

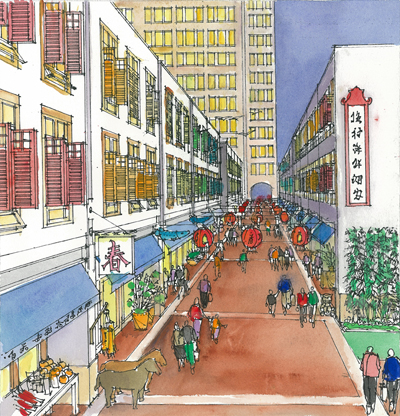

According to Dombrowski, some of Cheng’s plans include a Chinese merchandise mart, as well as various Chinese restaurants and groceries. Other plans include a Chinese-style public garden, a Chinese theater and a Chinese architecture entrance gate. Cheng has been meeting with potential Chinese businesses along the East Coast and in China, trying to lure them to what he sees as a new hot spot for American-Chinese relations.

As many American cities’ Chinatowns have faded into a few blocks as Chinese immigrants migrated to the suburbs, it’s rare for a new Chinatown to suddenly emerge. But, according to experts, Baltimore has its advantages, both in low land costs and its function as a port.

Bringing back a Chinatown to a city can be challenging, but not impossible, said Susan Fainstein, professor of urban planning at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University.

“Baltimore is an inexpensive place to do business,” Fainstein said. In New York City and San Francisco, which both enjoy thriving Chinatowns but on expensive land, “it’s hard to maintain a relatively low cost of enterprises in a central area. Baltimore is workable.”

However, due to the economic turndown, Cheng has run into a few walls in recruiting investors, McCoy said. Dombrowski expects about $1 billion in private investment in the next 10 to 15 years of the combined Chinatown and arts district, of which Chinese architectural touches may be added in some outdoor décor, he said.

Rather than exclude anything that is not Chinese, McCoy said the plan is to create a modernized Chinatown. “He doesn’t view this as being any kind of ethnic island, but rather a retail-residential area with an Asian flavor,” McCoy said.