Difficult to say goodbye

Updated: 2012-08-30 09:10

By Han Bingbin (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Ming and Qing Street in Beijing Film Studio is almost deserted and closed to visitors. |

|

|

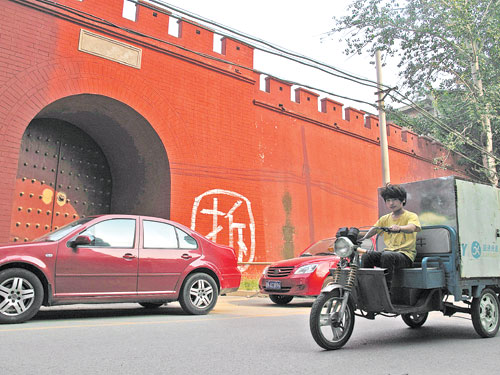

The Chinese character of "chai (demolish)" is painted on the wall of Ming and Qing Street. |

|

|

Demolition work starts at the Beijing Film Studio. |

|

|

One of the major structures by Ming and Qing Street waits for its turn to be torn down. |

|

|

Workers move filming equipment out of a warehouse in the studio. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

After more than 40 years at its current location, Beijing Film Studio is being demolished and moving to a swanky site on the outskirts of the capital. Han Bingbin finds out why the move is causing anxiety.

By the time the news is out about the demolition of Beijing Film Studio, China's oldest film shooting base and one of the capital's must-go tourist destinations, many Chinese movie fans are already too late to take a last look.

The studio's two most important film sets, the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) Street as well as the Rongning Palace, stopped receiving visitors on July 27. The walls of both buildings are painted with huge Chinese characters "chai (demolish)". The rusty iron doors are shut.

What's locked inside are silver screen memories cherished by generations of Chinese. They include some of the most successful productions in Chinese cinematic and TV history such as screen classic A Dream in Red Mansions (1987), international award-winning movie Farewell to My Concubine (1993) and the most-watched TV series among Chinese viewers worldwide, Princess Pearl (1998-2003).

Part of the land will be used to build residential buildings for an affordable housing project that is now under construction.

The China Film Group Corporation (CFGC), which is the owner of the studio, has kept a low profile so far as to what will become of the rest of the studio, located on a commercially-valuable land right beside the North Third Ring Road.

It has been widely reported that the land will be used for a dream factory project called Beijing Creative District, jointly initiated by the film group and a Shenzhen-based real estate company. The project includes a movie-themed hotel, a high-end shopping mall and a cineplex.

When Beijing Film Studio moved to where it is now, in 1971, it was surrounded by farmland. But over the years, the district has become a densely inhabited golden mile. Though the business value of the land has increased, the development of the studio has met its bottleneck.

Han Sanping, head of China Film Group Corporation, said to local media that the location as a film shooting base is no longer cost-effective due to its scale.

Therefore, starting in 2008, the group started to relocate its shooting facilities to the company's newly built film base in Huairou, on the outskirts of Beijing. The new base now has 16 studios, including the world's largest, spreading across 5,000 square meters, and has a production capability of 80 movies, 200 made-for-TV movies and 500 episodes of TV series a year.

In fact, as China Vision Media Group's vice president Yang Jinsong told the Beijing News, Beijing Film Studio started their relocation plan as far back as 10 years ago. As the industry develops, he said, it's a must for factory-like film bases to move to the quieter, cheaper and larger suburbs.

But Zhao Ningyu, movie professor at Communication University of China, feels sad seeing the country's time-honored film bases being demolished one after another to give way to urbanization. Over the years, when the Changchun Film Studio and Shanghai Film Studio both had one of their old film bases demolished, and when E'mei Film Studio announced its plans to convert one film base into a cinema, Zhao expressed his grief through his micro-blog. But he admitted that the companies have taken bold steps to "sell land for a second career".

"If Beijing Film Studio didn't give up its land, how can it raise enough money to have a second site at Huairou? How can it afford new shooting facilities?" he said.

While industry insiders empathized with the situation, the studio's old employees are disappointed with the move.

"Beijing Film Studio belongs to 500 employees, not just one person," says a 74-year-old retiree who asked not to be named. She feels that the company should have negotiated with employees before coming to a decision.

She has worked as a dresser at the studio since 1958. She is proud that her name has appeared in the closing credits of many classic Chinese films. Witnessing the film sets being demolished is like dismantling her own home, she says.

In a campaign to motivate her fellow workers to stand up against the demolition plan, she collects relevant news reports and the studio's old photos, and displays them in a public space inside the studio. Next to the clippings and photos, she hangs a white board to collect the signatures of those who oppose the demolition plan.

So far, she says, she has collected nearly 200 signatures, including renowned veteran actors such as Ge Cunzhuang, father of Cannes International Film Festival best actor award winner Ge You.

On Aug 25, this group had a gathering in which they donated money with a resolution to continue their collective protest.

Earlier, a group called "Beijing Film Studio employees and retirees" wrote a letter to the capital's cultural heritage and city planning authorities to urge them to punish those who destroyed three structures within the vicinity that have been listed in the "Beijing Outstanding Modern and Contemporary Architecture Protection List".

According to regulations, listed buildings are not allowed to be demolished, remodeled or expanded. If the valuable property has to be moved because of public construction, they should be relocated to another place as a whole.

Their efforts have paid off. On Monday, the Beijing City Planning Commission demanded that the three major buildings at Beijing Film Studio be preserved.

Lu (who declined to give her full name) from Sichuan, 65, has been an acting extra for five years. Even though she is a veteran, she gets only about three scenes a month and earns about 50 yuan for each scene. But she says she's happy because money is not her sole motivation.

She is concerned that once the studio is housed within a leisure center, extras like her will no longer be allowed to wait at the gate for a chance to be picked by casting directors.

The distance and transportation cost to Huairou will also make it not viable for her. Living with her son in downtown Beijing now, moving to Huairou is out of the question to satisfy her "little hobby", she says.

Another extra, 17-year-old Li Hongru, who dropped out of high school to pursue her dream of becoming a film star in Beijing, says she will stay optimistic for now, hanging onto the promises of her colleagues who told her that the film studio will find a new place for the extras to gather after the old studio is demolished.

"The old dream place is gone. But a new one will emerge," Li says.

Contact the writer at hanbingbin@chinadaily.com.cn.

Lin Tongfei contributed to this story.