What Che saw

Updated: 2012-09-16 08:10

By Mike Peters, Michael Franklin and Jonathan Stefonek (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

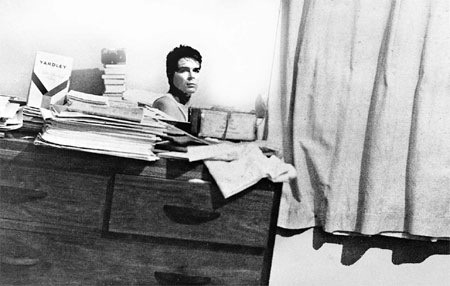

One of many self-portraits Che Guevara took in Tanzania, a period after an aborted armed struggle in Congo left the Marxist revolutionary in doubt about what to do next. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

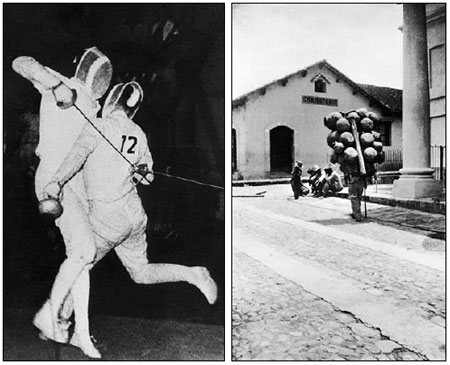

A fencing duel in Mexico and a street scene in Guatemala were captured by Che in the 1950s. |

The revolutionary hero's son brings a lifelong collection of Guevara's photographs to Beijing, and tells Mike Peters, Michael Franklin and Jonathan Stefonek why they are important.

|

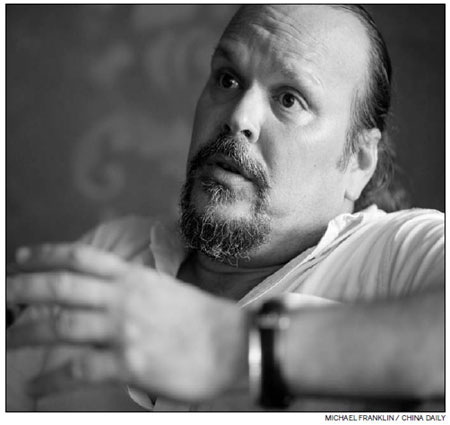

Camilo Guevara is holding a very odd press conference.

After coming thousands of miles to meet the assembled reporters, he won't sit at the center of the table. He doesn't want a microphone, preferring to let only the Chinese translator's voice carry across the sound system. He tolerates the photographers but he never poses.

He's not shy, and he has plenty to say. But the man wants to keep the focus on another Guevara. That would be his father - the man the world knows simply as "Che". The eldest son of the revolutionary hero is here to present an intriguing photography exhibition.

While the most famous image of Che Guevara has become a pop icon, the show his son has brought to Beijing is designed to "turn the tables" and put his father on the other side of the camera.

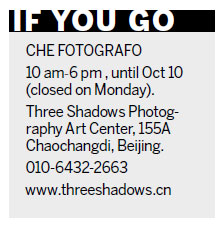

That was a place the revolutionary hero was happy to be, says Camilo Guevara, who is the guest curator of the collection of 238 photos on display until Oct 10 in Beijing.

"He enjoyed the moment of taking a picture," he says of his famous father. "But he didn't put too much effort into conserving those photos." But while Che once said it was important to make a photographic record of the revolution "so the truth could not be refuted", the revolution is almost absent from this exhibition.

His son says that during Che's many guerilla campaigns "the priority was on saving lives, on winning the battle." In the 1950s and '60s, there were no point-and-shoot digital cameras. The hobby required film, processing, paper and time.

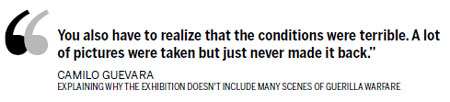

"You also have to realize that the conditions were terrible," says Guevara, noting that his father's men slogged through jungles and rivers with the precious pictures on their backs. "A lot of pictures were taken but just never made it back."

One such case makes a poignant ending for one part of the exhibition, a video of Che's life. The narrator recounts that when the guerilla leader was finally hunted down and killed by Bolivian soldiers and US agents, the personal items discovered with his corpse included 12 rolls of undeveloped film. The last pictures his father took, Guevara says, are lost to history - at least for now.

The fact that only about 1,000 images have been found from years of photography give special purpose to the Che Guevara Center, which his son now directs. Conserving such material is part of a UNESCO project called Memory of the World. The aim is to preserve artifacts - photographs, books and notes - that document the history of important people, and then spread that history around the world. The Che photos are a grab bag: travel photos, industrial studies he snapped as a government minister, and some eye-opening self-portraits.

"Over the course of hanging the show," says Jillian Schultz, curator of the Beijing exhibition, "thrilling little details emerged which had previously escaped me: a tiny figure all in white in front of a huge pre-Columbian monument, a blurred child's head popping into the bottom of the frame while capturing the construction of the Camilo Cienfuegos school." These details made her recognize Che's passion for photography, a side of the legend she'd never known.

Viewers of the photographs - which were first exhibited in Cuba in 1991 and have toured in Europe and Latin American since then - seem most taken with the collection of self-portraits that comprise the last one-third of the show. That fascination is just as intense for Guevara, who was 5 years old when his father was killed.

"They had to be taken with discretion - he was in hiding. In those moments, he was alone, in those empty rooms, and the value is that we can see how Che saw himself."

Some of the most intimate pictures were taken in Tanzania, where Che fled after his troops were forced to leave the Congo, one of many places "the Comandante" tried to export Cuba's revolution. Viewers familiar with a bearded Che in commando garb may be startled to see him in a suit, a fedora and a toothbrush mustache.

We learn that was a disguise (complete with false teeth) that Che wore to his refuge in Tanzania, and subsequent photos reflect Che's impish glee as he presents himself to his unsuspecting wife, Aleida. In other pictures from that period, Che adopts casual and semi-sensual poses reminiscent of movie stars of that era like James Dean.

More Che humor - or a little myth-making of his own?

Camilo Guevara never pretends to know what was in his father's mind when any of the images were taken.

But he has found the spirit of the man who took them to be constant.

"For Cuban people, Che Guevara was an example of a human being, a person who was a doctor, a photographer and a politician - a real person with different sides. His thoughts and his values are reflected in every aspect of his life, the way he lived his life. He was an example of how a human being should live."

The revolutionary's life was shaped by his tour of Latin America as a young Argentine medical student. Later he described how he came in "close contact with poverty, hunger and disease" along with the "inability to treat a child because of lack of money" and "stupefaction provoked by the continual hunger and punishment" that leads a father to "accept the loss of a son as an unimportant accident". Those experiences ultimately convinced him that armed struggle, not medicine, was the key to helping such people.

But the intimately personal photos of Che from Tanzania shouldn't surprise anyone, his son says with a hearty laugh.

"I am proof that Che Guevara had a private life."