30 years of Music - how it changed

Updated: 2012-09-20 13:35

By Ginger Huang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

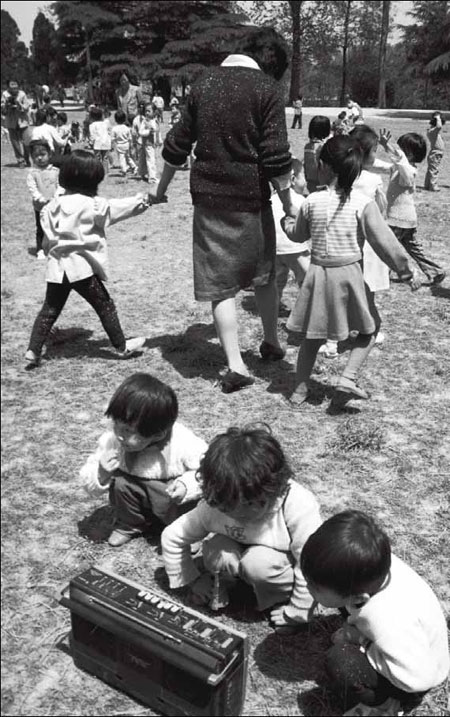

In the 1980s, recorders that could both receive radio and copy a tape became popular in China. Provided to China Daily |

How junk cassette tapes and hungry music fans gave rise to the modern Chinese music industry

Fan Yue, now a 40-year-old music teacher in a Zhejiang province high school, still remembers how her heart panged when she first heard Teresa Teng as a 7-year-old in 1979.

"I went to my cousin's house with my parents and heard music wafting out of his door. I was awestruck—how could music be so sweet!" She recalled.

"However, my cousin and his teenage friends wouldn't let me in. They just laughed and said I was too young for it. Teresa was said to be unhealthy for youngsters."

Fan's cousins epitomized the shocked response of the majority of Chinese people to the alluring beauty of the oval-faced Teng. She was a revelation, particularly as prior to 1978 the "cultural revolution" (1966-76)'s aestheticism had all but obliterated the country's musical taste.

People thus began the 1980s starved of music that touched them emotionally.

Teng swept onto this scene like a whirlwind, singing, "When will you come to me again, after we part tonight?" The nation swooned.

Following in Teng's dainty footsteps, "campus folk music" (校园民谣 xiào yuán mín yáo) from Taiwan became popular with adolescents in the late 1980s. It featured guitar-strumming vocalists singing softly about light-hearted subjects like rural life, childhood memories, campus relationships and adolescent blue moods.

Teng had kick-started a decade-long fascination with sentimentalism that pervaded TV, films, literature and most of all, pop music.

However popular love ballads and campus music were in the early 1980s, they were frowned upon by the mainstream, just like bell bottoms and permed hair.

Pop music was allocated only a short time slot on the radio, if it was given any play at all; most of the radio stations played propaganda tunes called "main theme music"

(主旋律歌曲 zhǔ xuán lǜ gē qǔ).

They were patriotic and dedicated to praising the glories of the reform period, yet as with many revolutionary songs, they became popular, especially among middle-aged people, because of their melodies.

In 1985, Chinese people still had little idea of what a live concert was like. When Wham! became the first Western band to visit China that year, enterprising scalpers sold

tickets for five times their original price.

Tapes were given out for free with the tickets, making Wham!, one of the earliest Western bands to become familiar to Chinese audiences.

The 1990s brought about chaotic commercialization and a godsend for music lovers: dakou (打口dǎ kǒu) tapes. These were surplus cassettes that Western music labels had marked for destruction by etching a deep cut into their cases. They were shipped to China and sold by the ton as junk plastic. Through various middlemen, the tapes were recycled and eventually resurfaced in music stores and university campuses.

Dakou not only introduced a generation of young people to Western music, but also nourished some important Chinese musicians.

"In 1993, Qian Dacheng was the ‘godfather of Chinese dakou tapes.'He imported a ton of the junk plastic tapes at a price of 4,000 yuan a metric ton, hired some college students to sort them out and sold them at Avant Garde Music in the Wudaokou area of Beijing. Tang Dynasty bought loads and Dou Wei was also a frequent visitor. Pu Shu was too poor to afford any, so he used to sit in the store all day long, just listening," Chinese GQ wrote in a 2010 profile on Zuoxiao Zuzhou, a musician who at that time made his living selling dakou in Shanghai.

Dakou music gave way to music downloads circa the launch of free online music sources such as Baidu MP3 in 2002. The listening experience became less of a public event and a more personal, introverted pursuit.

"As it gets easier and freer to listen to music, I get lonelier," former dakou collector Ren said. "It's so hard to find someone to talk to about music. But I'm not nostalgic. I don't want to go back."

Xiami, a music website founded in 2006, goes some way toward solving this dilemma. Its idea of a decent peer-to-peer music download platform soon attracted like minds, who also used it to share personal opinions about the music they were sharing.

Now Xiami allows users to listen to music for free, while downloading a song costs 0.8 yuan. If music from your computer is shared when someone else downloads a song, you receive 0.2 yuan.

Meanwhile, Baidu MP3 consistently defended copyright infringement challenges by claiming that it merely linked to third-party download sites, the content and legality of which it couldn't be responsible for; a stance that has allowed thousands of similar sites to thrive in its shadow.

But these developments are simply too little and too late for some in the domestic music industry.

In 2011, Song Ke, the manager of Taihe Maitian, the largest pop music label on the Chinese mainland, announced his company would

no longer be signing new contracts and would not even renew its deal with Li Yuchun, the megastar winner of the immensely popular

Super Girl TV singing contest.

"Record companies hate piracy, and even those who make pirate CDs hate piracy, as even they can't make any money out of doing it anymore ... If you want to promote your music, it's better to just get Yao Chen (the Weibo queen) to do it rather than join a record company," Song said in an interview with the Xiaoxiang Morning Post.

Nowadays, he can be found enjoying a retreat from the vagaries of the recording business at the helm of his very own roast duck restaurant.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily 09/20/2012 page27)