Chef for life

Updated: 2012-09-24 15:32

By Xu Junqian (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

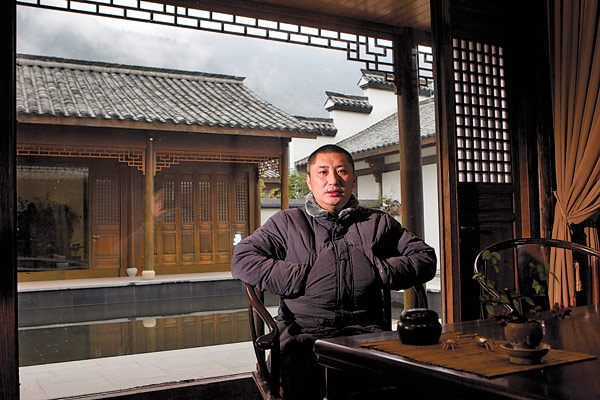

For Dai Jianjun,the process is the most important part of food production, and he laments that traditional expertise is lost as members of farming families now seek their fortunes in cities instead. Photos by Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

Dai Jianjun's island hideaway near Hangzhou is a natural temple for sustainable food, but he tells Xu Junqian that it's a national, even international model.

Coming over to Dai Jianjun for dinner requires a half-hour ferry trip from Hangzhou in Zhejiang province to this nameless, addressless island where his dining table is set. And before crossing the threshold, hide all your snacks so the gastronome doesn't start talking about the "poison chemicals" you seem to have confused with "food".

Do those things, and in return, the man who calls himself the most "savage" restaurateur in China may treat you a table of nowhere-else-to-be-found divine delicacies. The components of your meal, from the sauce to the toppings, can be traced in the thousand-square-meter farm at the back of his kitchen, in the vast expanse of the island.

"The reason that people nowadays no longer act like human beings is because the pork they eat, the vegetables they are fed, no longer taste like meat and greens," the 43-year-old Hangzhou native says.

After running his organic restaurant, Longjing Manor, by the majestic West Lake in Hangzhou for nearly a decade, Dai decided to become his own supplier three years ago by starting a farm here in Suichang, Zhejiang province. He'd watched as the integrity of his ingredients became "severely threatened", with the ever-increasing pollution in the heavily industrialized area and the declining passion of local farmers to toil diminished, even when he offered to pay two to three times the going rate to get the quality he wanted.

"I don't want to brag what a nation-saving course I am undertaking. As a born glutton, however, I just want to keep my bowl as desirable as my ancestors', if not better," he says, describing how China's 5,000 years of refined agriculture has been seriously disrupted, if not ruined, in the past several decades.

The farm, named Gonggeng College, (meaning tilling in person), is more like a resort, a walled garden, or simply, a paradise, with fruit yard, fish pond, vegetable field, green-tiled manor houses, and everything else you might imagine in a perfectly idyllic scene.

The island itself is tiny, pristine, secluded. It is inhabited by a small handful of farmers and their families. The only motorized vehicle here is a runabout that is used for shuttling people between the farm and the dock. Nine rides out of 10 are accompanied by Helen, the farm dog.

"I want to create an ideal lifestyle here advocated by our ancestors as 'three-cry', which is waking up at the cock's crow, check at cicada's chirp and going to bed at frog's croak," he says.

Dai is the only Chinese restaurateur to be honored by Italy's Terra Madre, a world network promoting sustainable agriculture, and the global Slow Food movement for his contribution to natural foods and natural way of cooking foods.

Dai has a detailed and strict system as to how every kind of food should be cooked and served. Lake fish, for example, has to be stewed in the water from the same lake that the fish is caught so that the essence of the fish meat could be preserved and highlighted. Cabbages can be only hand-torn before frying with lard, as the iron of a metal blade would spoil the taste of the cabbage.

But the "bowl-keeping" course doesn't come easy, or cheap.

For the past three years, since the first pillar was set based on the blueprint Dai drew himself, tens of thousands of yuan have been lavished and lessons have been learned from failure. No chemicals or artificial additives that are taken for granted in daily life but do harm to the environment have been allowed either during the building of the farm or in the ongoing routine of life.

For example, pesticides have been replaced by boiled pepper water to drive away pests from the vegetables and mosquitoes from humans. And hens and cocks are carefully raised and matched to produce the best quality of eggs, which must be hatched by hens rather than artificial lights.

But the most difficult part for Dai is to find enough experienced farmers, who are the living textbooks of all these "outdated but smart" tricks, to help him maintain the desirability of his bowl.

"I hold nothing against urbanization or civilization, but the culture is now boosting one by playing down another, which has taken millions of young and old in the countryside away from the field," he says.

"I still remember when an aging farmer, with a weatherbeaten face, knelt down in front of me with his best chicken after a chatty lunch and received some groceries I brought to him from cities."

Dai has now established a network of more than 100 farmers across the country both to scout his supplies for food and help them with their lives.

Dai says visitors are at liberty to pay for a stay at his college, as he aims to simply "offer an alternative for many Chinese people to know that they can live in other ways". Meanwhile, his restaurant in Hangzhou, which has eight tables but is fully booked all year-round even while charging a minimum of 1,000-yuan a table, is a Robin Hood-style business. "Robbing the rich and helping the poor," he explains.

A galaxy of business people, literati, artists and government officials have supported Dai, who says his culinary philosophy is nothing but "to eat local and eat seasonal". And he believes it could be a model for the nation one day, though he still doesn't know how.

"At least we have started. It's like planting a tree. Even if it takes a century to grow into a forest, we would have a forest a hundred years later if we plant the seed today," says Dai.

Contact the writer at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

|

Photos by Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

|

|

Photos by Gao Erqiang / China Daily |