Sails fly again on glorious junks

Updated: 2012-10-05 07:09

By Zhang Lei (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

An exhibit in Zheng He Park in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, in July. On display were models of junks of Zheng's fleet. Qin Huai / For China Daily |

Craftsman preserves the artistry of the GREAT Chinese vessel in miniature

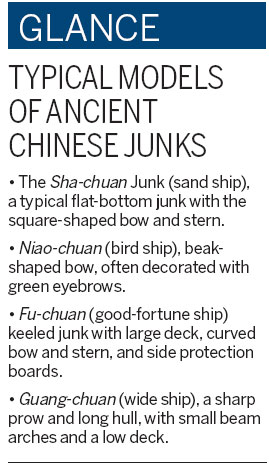

Well before Columbus discovered America, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) mariner Zheng He led a commercial fleet of more than 200 junks from China's shores to places as distant as the Red Sea.

So adaptable was the vessel, it would take another 600 years before the wooden junk had had its day. Since the 1990s, steel vessels have gradually been replacing them in most Chinese river networks.

One of the last traditional boat builders to succumb to modernity was Lu Xiehe, who closed his boatyard on the Fuchun River in Zhejiang province in 2008 when local government cuts affected waterway management.

But in an effort to stop an old craft slipping into oblivion, Lu embarked on a voyage of rediscovery.

"I made my first replica junk in 2005 purely as a hobby," he says. "With one of my friends from the local boat makers' association who had plenty of spare time, we bought some basic materials and spent half a month finishing a 60 by 250-centimeter replica junk."

Used to building junks as big as 60 tons, Lu was surprised at how fast he learnt to make miniature replicas.

"Forgive me for being immodest, but I don't think there are many people out there who can make a better wooden junk than me," he says. "Many can make random small junk artworks, but few could make a scaled-down replica that stays in proportion with the real one in specific measurements."

At 62, he believes he is the youngest living master of the old art. In 2009, Lu's style of wooden junk making was listed as an intangible cultural heritage of Zhejiang.

His replicas are deemed the reincarnation of the real junk, in a smaller size. The building process begins with the keel set as the main frame, then the ribs are patched, shell and bulwark plated, and the deck added. The bridge and crew's quarters follow, then masts, anchors, capstan and rudder are installed.

"Making wooden junks requires not only the knowledge of a carpenter, but also a flexible mind, because carpenters usually make regular, symmetric things, while most of the stuff on the junk is irregularly shaped," Lu says.

"Blueprints are necessary, but real experience is indispensable. For example, there is no strict measurement for the curvature of the prow, but a minute change made to it could end up being a damper on the sails, and that's where your experience should come in."

It usually takes more than 10 years to learn the basics of junk making. Lu spent eight years as an apprentice to his father, building all manner of boats.

Today, much has changed but there is still sawdust everywhere. His replicas are basically made of China fir, camphor, pine and cotton cloth, and coated and sealed with tung tree oil.

"Although the procedure is simplified compared to making a real junk, it is still complicated," Yu says. "Different components need different wood materials. The baseboard uses pine, catalpa wood for sides, sassafras for ribs, and cypress wood lintels."

Painted symbols on the bow distinguish a river junk from a seagoing one. Sea junks are usually decorated with a "Great Ultimate" (yin-yang) pattern according to tradition, while river junks feature an eye and eyebrow. These ancient Chinese symbols are meant to bring peace and luck, and ward off evil spirits.

A black hull with green eyebrows on the prow signified a typical merchant or senior official junk from the days of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) in Zhejiang.

The history of junk building on Fuchun River can be traced back to the Three Kingdoms period (AD 220 - 280) when it was the imperial barracks yard for the East Wu Kingdom. It is believed many junk makers of Zheng He's great fleet came from Fuchun.

In 2010, Lu opened up his White Sail replica boat studio in Fuchun, although his first order was not exactly a replica, but a 10.5-meter oar propelled junk that could carry 24 passengers.

Lu, however, still reminisces about the days, not so long ago, when junks were a common sight on the river; about how, along the riverbanks, work songs were chanted by boat trackers to synchronize their movements as they hauled boats across shallows.

"Kids nowadays hardly catch sight of such bustling excitement any more," he laments. "All I can do now is make some replicas and perhaps at least trigger their imaginations and let them revisit our history.

"I hope through my small replicas they can somehow imagine the grandeur of the junks, and at the same time be charmed by the ancient boat builders' art."

zhanglei1@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 10/05/2012 page18)