The French connection

Updated: 2012-10-16 08:39

By Zhao Xu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

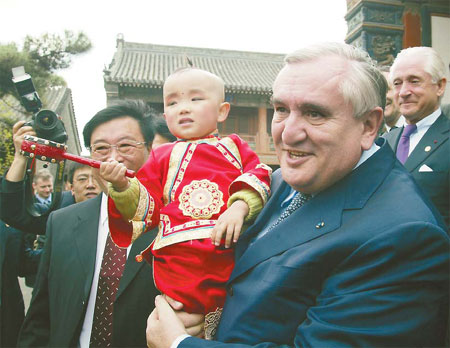

Former French prime minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin held a child when he visited the Shenyang Imperial Palace in Shenyang, Liaoning province, in April, 2005. Wang Qiang / for China Daily |

|

|

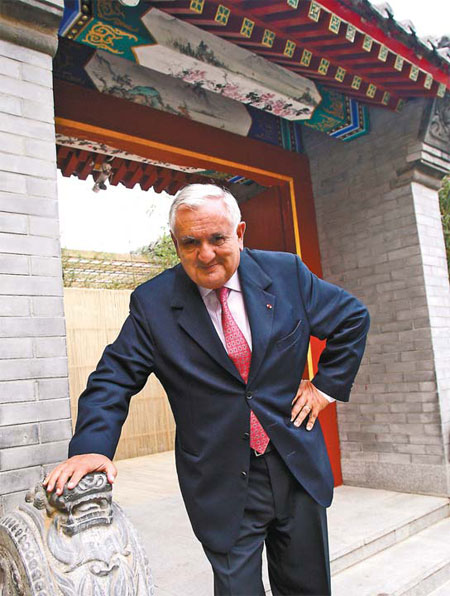

Raffarin says he always feels like a newcomer when he visits China. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

A former prime minister of France looks back at the close friendships he had forged in the Middle Kingdom through the decades and shares some of those memories with Zhao Xu.

When you hear a politician say that he has never taken an opposing view, your first reaction would most likely be: How could that be true? But Jean-Pierre Raffarin, who was prime minister of France from May 2002 to May 2005, insists it's true as far as he is concerned.

Raffarin, 64, made the remark while reflecting upon his first journey around China, undertaken in 1976, when he was 28.

"I was a student traveling with a French group from Harbin (Heilongjiang's provincial capital) to Shenzhen (in Guangdong province), and Beijing was right in the middle of that cross-country trip," he says, turning the clock back 36 years.

If there's something remarkable about a foreigner traversing the country in the mid-1970s, what rendered the journey forever indelible from Raffarin's mind was the fact that the group arrived in Beijing on Sept 9, the day Chairman Mao Zedong passed away.

"The nation was gripped by grief - everywhere, people were mourning," says Raffarin who, despite his own purely Western cultural background and political upbringing, had tried to read those bereaved faces he encountered on the streets to understand the sense of loss that had engulfed the country.

It was the memory of those few days that the former French prime minister, who had fought many political battles in his lifelong career, says that he had never belonged to the opposition when it came to listening to the people's hearts.

"You have to first understand before you talk," he says. "It was more important to share the feelings than to make judgments."

However, the sorrow was not the only thing the young Raffarin shared.

"From time to time, we came upon small boys and girls who had little comprehension of what had happened, and as they ran on the streets, their innocent and infectious smiles cast eternal sunshine on our minds," he says.

Members of the group were handed table-tennis rackets by the youngsters and invited to play.

"The results never changed - they always won," recalls Raffarin, trading sad memories for the moments of sweetness.

What had been won were not just the games but hearts as well.

"Those children represented hope - China may be poor and still in difficulty, but its people were rich in spirit," says Raffarin, who would go back to France and write a book titled Life in Yellow.

"What I intended to say through the book was that China would one day retake its place as a first-ranked nation. It needed a lot of time but it would happen. And we would all have to pay attention," he says.