Floating on sheepskin

Updated: 2012-11-15 10:31

By Lin Jing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

A boatman ferries a passenger on his sheepskin raft on the Yellow River in Lanzhou, Gansu province. Photos by Lin Jing / China Daily |

|

|

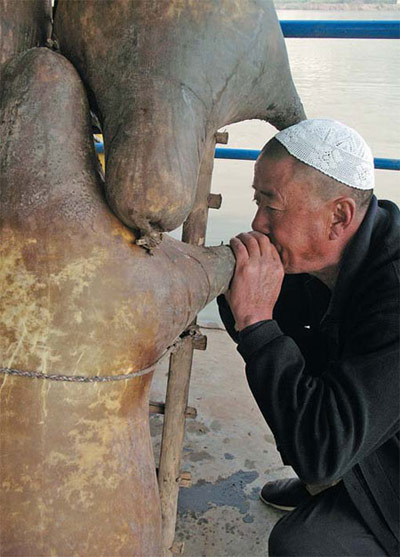

Zhang Debao blows up a sheepskin bag that will help float his raft. |

Gansu boatmen keep a hardscrabble tradition alive as they ferry tourists across the Yellow River. But the boats, made buoyant with sheep skins filled with air, may be gone in a generation, Lin Jing reports in Lanzhou.

Zhang Debao sits in the sunshine, staring at the translucent sheepskin bags on the Yellow River, which flows right through the heart of downtown Lanzhou, Gansu province's capital city.

The smoke from the cigarette between his fingers is blown away by the cold wind in early winter. After several crossings on his sheepskin raft, he needs a break. After all, he is already 60 years old.

"We will be the last group of sheepskin raft boatmen," says Zhang, shaking his head. "There will be no one to take over our trade."

Occasionally, there are some curious visitors coming for a look at the rafts made from sheepskin bags, for a glimpse into the cultural heritage of Lanzhou.

Sheepskin rafts can be traced back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), when soldiers used them to ferry men and goods during wars. Local residents in Lanzhou used them to shuttle passengers, fresh fruits and vegetables across the river.

The biggest barges are made from 600 sheepskin bags, while the smaller crafts, like those used today, are made from 13 bags, and used normally for short distances only.

Despite a long history, there is only a handful still in the business, and Zhang is one of the few who can still make the sheepskin rafts himself.

The process is long and arduous, strictly following the ancient methods.

Raft-makers will select sheep in November, when the animals are fat and have thicker skins. After butchering, they will use rapeseed oil to season the skin and make it water-resistant. The skins will be dried during the coming spring and summer, when they turn yellow and transparent. Then the skins are sewn into bags.

Zhang says that these sheepskin bags are inflated by mouth only. "A bicycle pump is no good for us. When you blow with your mouth, there will be more moisture in the air, which will give these bags a longer life."

Experienced boatmen can blow up a sheepskin bag within 30 seconds, while for others it may take about 20 minutes.

The shaving and cutting is the most difficult part, he says. With even one small careless scratch, the whole skin can be wasted.

"A sheepskin costs about 200 yuan ($32) each. The total cost of a bag can be over 400 yuan before it is ready for use," he says.

Hu Yongzhong, Zhang's fellow apprentice, says that in the old days, there were few cars or carriages on the roads, but almost every family would raise sheep, and so it did not require much money to construct a raft.

A sheepskin raft weighs about 12 kilograms and can be carried on the shoulder to cross the river instead of taking a detour across a bridge.

That's why these rafts became a major mode of transportation across the Yellow River. When going downstream, the raft ferries people; but going upstream, people have to carry the rafts on their shoulders.

"When sailing, sheepskins will be on the river and people on the raft. Not even one drop of water will splash on your clothes," says Hu to tourists coming to ride the sheepskin rafts.

The rafts are quite steady in the water.

Zhou Hongyu, a photographer from Liaoning province, is taking her first sheepskin raft ride.

"It is a little shaky, but the raft feels really stable and nothing gets wet," she says, with some excitement.

Hu is 48 years old and has been in the trade for more than 20 years, following the footsteps of his father and grandfather.

There is little overhead cost, but the work depends very much on fair weather.

Boatmen start work from May to October each year, with peak seasons in July and August.

During the cold months, boatmen take time off to repair and make new sheepskin bags for their rafts.

Each ferry operator can make 4,000 yuan per month during peak seasons. And during spring and at year's end, there are barely any tourists, so they have to make enough money during the busiest months.

But this year, he says, due to the flooding of the river, they were prohibited from running the rafts for a few weeks.

It takes a lot of work and care to repair and maintain the rafts regularly.

Hu says that if treated carefully, one sheepskin bag can be used for three to four years. Otherwise, they have to be replaced in a year.

Every day the boatmen will take each sheepskin raft out of the water and dry it in the sun. Before putting the rafts back into water, they have to blow into the sheepskin bags to make sure every one is ready for use.

Every month, the rafters also prepare a mixture of salt water and linseed oil to moisturize the insides of the sheepskin bags. They use about 500 grams of the mixture per bag. But each year, they have to prepare at least 50 new sheepskin bags ready for use.

Zhang Debao has been in the business for more than 40 years and he says it is really hard to find any successors for the future.

"Many elders in this industry have passed on and young people nowadays are not willing to pick up this skill because it is smelly and filthy when making sheepskin bags," he says. "The skill may be lost after our generation."

He says the smell of sheepskin is like "rotten meat" during the shaving process. And the daily maintenance work is another headache for beginners.

"Few are willing to put their mouths on a smelly sheepskin bag," Zhang says.

In his family of two brothers, Hu is the only one who took over the business from his father. Hu says that after their fathers passed away, he and Zhang now run their business together - and are also the only ones who can still make the sheepskin bags.

He has two daughters, and Zhang has one son. But none of their children are willing to learn because of the nature of the job, also because it does not pay well.

"I am almost 50 years old and can work for another 10 years at most," says Hu. "Though it is hard, we are still hoping to look for apprentices." And for the two raftsmen, the search goes on.

Contact the writer at linjingcd@chinadaily.com.cn.