Farmers begin to gradually sow the seeds of change

Updated: 2011-12-20 08:07

By Wang Ximin and Zhao Huanxin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Workers at a distribution center in Shouguang city, Shandong province, select hot peppers for supermarkets. Shouguang has annual vegetable yield worth 4 billion yuan. Seeds companies around the world eye the big Chinese vegetable center. Ju Chuanjiang / China Daily |

|

People visit a vegetable expo held in Shouguang, Shandong province in April. Dong Naide / for China Daily |

Foreign products taking root among growers of greenhouse vegetables, Wang Ximin and Zhao Huanxin report from Shandong province.

Liu Mingshan, a farmer in Daotian township in Shouguang, the country's leading vegetable producer, said he prefers foreign seeds to domestic ones. "They are higher yielding and more resistant to disease than those developed by Chinese firms."

The veteran greenhouse vegetable grower pointed to a hybrid fruit cucumber from a Republic of Korea company. "It tastes great and sells well."

Bitter news, perhaps, for some agriculture officials and breeders. Foreign varieties have taken more than half of the seed market for major greenhouse vegetables in Shouguang, in East China's Shandong province, and for higher-grade vegetables in China, according to the Ministry of Agriculture's seed management bureau. Industry insiders say, however, that the country should recognize competition renders more choices to farmers and consumers and spurs the fledgling seed industry.

Foreign businesses supply seeds for almost all of the greenhouse fruit cucumbers (with no thorns) and sweet peppers and 80 percent of tomatoes, eggplants and melons in Shouguang, a city of 1 million residents.

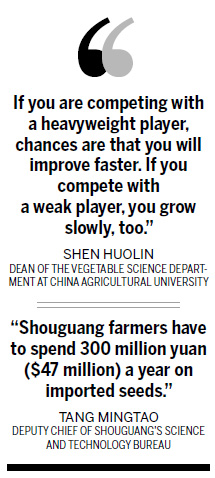

"Shouguang farmers have to spend 300 million yuan ($47 million) a year on imported seeds," Tang Mingtao, deputy chief of the city's science and technology bureau, told China Daily.

Two-thirds of the revenue to the local seed market goes to foreign companies, he said. And foreign seeds are distributed through Shouguang to other parts of Shandong, the largest vegetable-producing province in China.

With an annual vegetable yield worth 4 billion yuan, Shouguang is the "vegetable city" that multinational seed companies cannot afford to neglect.

A speedy response

The world's top 10 seed companies, including Switzerland's Syngenta, the Netherlands' Rijk Zwaan and Israel's Hazera, are active players in the Chinese market. They have set up breeding bases or research facilities in Shouguang.

In July 2009, when tomato yellow leaf curl virus overran the greenhouses in Shandong, not one Chinese seed businesses could provide a timely solution, Tang said.

Hazera Genetics, which entered China in 1999, provided tomato varieties resistant to the virus within a few weeks, allowing local growers to re-sow soon, said Yossi Tzuri, Hazera China's CEO.

The price of the virus-resistant seeds and strains was more than double that for earlier versions of tomato, Tang said.

This anecdote and others are so deeply rooted in the minds of some local growers that they have grown to distrust Chinese vegetable brands, said Shen Huolin, dean of the vegetable science department at China Agricultural University in Beijing.

After 12 years of research and development, the professor and his team cultivated a premium long horn-shaped chili pepper variety, known as Zhongshou-12, that is proven better than its foreign counterparts in product quality and resistance to pests and disease.

"When a zealous farmer came to me for more seeds after a trial run," Shen said, "I offered a discount, which was half the price of foreign pepper seeds. To my chagrin, he said that since it was not a foreign make, the price should be still lower!"

Use and value up

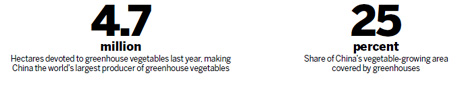

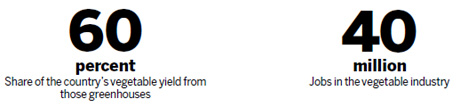

China's mammoth vegetable sector used nearly 100,000 tons of seeds to produce 650 million tons of vegetables last year, according to Liao Xiyuan, deputy chief of Ministry of Agriculture's seed management bureau.

The influx of foreign seeds has been rising, Liao said. By December 5 this year, for example, the import value hit $121 million - 3.1 times the value in 2004, Liao cited Customs figures as saying.

"The majority of Chinese greenhouse vegetable seed companies are not capable of breeding and producing seeds or possessing copyright varieties," said another bureau official, who preferred unidentified. "They are mainly agents or producing and marketing some conventional seeds."

He said that overseas seed companies have grabbed 15 percent of the Chinese greenhouse vegetable market and nearly 20 percent in Shandong.

Foreign seeds are usually several or dozens of times more expensive than the homebred, he said. That explains why the value of Chinese seeds, which hold 80 percent of the Shandong market, equals just 20 percent of the imported seeds' value.

Because foreign seeds boast higher germination rates and promise good results, local seedling companies would buy them regardless of the price, said Wang Rui, an executive with New Century Breeding Co in Shouguang.

Nearly all seeds the company uses come from Israel, the Netherlands and Japan, and orders have been already placed for next spring's seedlings, he said. "Shouguang farmers think it pays off to buy such shoots, because better harvest and high-quality products are usually guaranteed."

Marketing matters

The situation in Shouguang has aroused intense discussions in Chinese newspapers, which claim in editorials that the country's greenhouse seed market "risks being monopolized by foreign firms" and that it has to reclaim "the losing battleground".

However, Zhang Zhenhe, chief specialist from the National Agro-Tech Extension and Service Center, said people needn't make too much fuss. "What happens in Shouguang is a special case; it is not representative."

Thanks to its well-developed marketing channels, Shouguang never needs to worry that its produce will be stockpiled even though farmers elsewhere fret about oversupply and price drops.

"Growers in Shouguang are much more market-oriented," Zhang said. "They choose foreign seeds with alacrity to pursue profits and reduce risks, and the benefits can always offset the cost of the seeds."

Foreign seeds are used less in other parts of the country where the market is not as mature, Zhang said. He estimated that the acreage sown with foreign seeds remained below 600,000 hectares a year in China from 2007 to 2010.

But adoption of foreign seeds has benefited growers and consumers, who increasingly care about the quality and safety of their vegetables. "Some varieties are not indigenous, so imports have enriched China's product portfolio," Zhang said.

Competitive boost

Shen Huolin of China Agricultural University said the presence of foreign seed companies has intensified competition in the vegetable sector, as in other industries.

"If you are competing with a heavyweight player, chances are that you will improve faster. If you compete with a weak player, you grow slowly, too," Shen said.

Sean Wang, chief of Syngenta China's corporate affairs, said: "Competition spurs innovation and investment and drives quality improvements to meet the needs of customers."

By co-existing with foreign rivals, Chinese companies are working hard to try to get closer to their level. They have even surpassed them in some areas, Shen said. "In this way, the seed market will not be monopolized by foreign firms."

China Agricultural University and the Shouguang government are running the Shouguang Vegetable Research Institute to help boost national vegetable seeds industry, Shen said.

Over the past five years, it has developed eight vegetable varieties - four sweet melons, two peppers and two towel gourds - that have reached international advanced level, according to Zhao Zhiwei, a manager with the institute's experimental base in Shouguang.

Removing the snags

Zhang Baoxi, deputy director of the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, said foreign companies' advantages in greenhouse vegetables were built on a long history of research and massive investment.

In comparison, Chinese seed breeders began to give priority to greenhouse varieties only in the early 2000s.

"For a long time, Chinese breeders focused only on seeds for outdoor vegetables, especially the crops with higher yields during early growth period," Zhang said. "They somehow unconsciously dropped the strains fit to grow in greenhouses."

Unlike in foreign countries, the major players in seed breeding in China are institutes at universities and academies, rather than enterprises, he said.

It usually takes at least 10 years to develop a vegetable variety, but seed researchers in these institutes are often funded by government projects that last about three years. This means researchers spend much energy seeking new projects to maintain funding, Zhang said.

Some institutes run their own companies, usually to finance research, but often without forging tight links with the market, he said.

"It is safe to say that China's whole input in vegetable research is less than that in a single foreign company," Zhang said. For instance, Syngenta spends roughly $1 billion on research and development annually, according to a company statement.

For China's vegetable industry to thrive, it must protect intellectual property rights, both Zhang Baoxi and Shen Huolin said.

"Sometimes you have developed a popular new variety, but in less than three years, you'll find that the area sown in this variety through illegal seed distributors is far greater than the area with seeds from legal channels," Zhang said.

Some individuals even steal technology, Shen said. "For example, by combining the excellent traits of two varieties, both of which were obtained through illegal means, individuals could easily concoct a hybrid with better quality than the original."

Shen claimed that some vendors paid cash to breeding farmers who had grown Zhongshou-12 peppers in his production base outside Beijing to get nearly all the seeds they harvested this year.

"I should have gotten several thousand kilograms of seeds, but I haven't gotten a single gram," he said.

The seed bureau's Liao Xiyuan vowed the Ministry of Agriculture would foster large seed companies in China through acquisition. At least 8,700 seed companies are registered in China, but only a small fraction are large and have adequate R&D capacity, the bureau said. The country will also "drastically" invest in development while improving extension service and market regulation, Liao said.

Looking ahead

Back in Shandong, the Shouguang Vegetable Industry Group invested 150 million yuan last year to set up a seed company, including a pilot base for vegetable breeding, said Tang Mingtao of the city's science and technology bureau.

The Zhongshou-12 pepper variety developed by Shen Huolin's team has now been planted in at least 667 hectares, more than half of the chili pepper-growing area in Shouguang.

Asked about the goal in the coming five years, Shen said he anticipated Chinese seeds would be used in 30 percent of all greenhouse vegetable planting area in this "showcase of China's vegetable industry".

Ju Chuanjiang and Zhao Ruixue in Shandong contributed. Write to wangximin@chinadaily.com.cn and zhaohuanxin@chinadaily.com.cn.