Rail dream still on track to unite continents

Updated: 2011-10-12 07:56

By Alfred Romann (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

![A train runs on the 100-year-old railway linking Kunming in China with Vietnam. The line is only a small part of the Trans-Asian Railway. [Photo / Xinhua] Rail dream still on track to unite continents](../../attachement/jpg/site1/20111012/0013729e48090fff1bcd09.jpg) |

|

A train runs on the 100-year-old railway linking Kunming in China with Vietnam. The line is only a small part of the Trans-Asian Railway. [Xinhua] |

Major problems remain but ambitious network hopes to link Asia to Europe, Alfred Romann reports from Hong Kong.

Creative locals use "bamboo trains" to travel along Cambodia's abandoned railway lines. These homemade vehicles ferry food and people and are powered by adapted water pumps. Technology at its most basic but Cambodia's railways could yet be part of an ambitious network linking Asia to Europe.

In 2009, the Asian Development Bank provided $84 million to rebuild Cambodia's 600-km railway network. The whole project should cost $141 million and is due for completion by 2013.

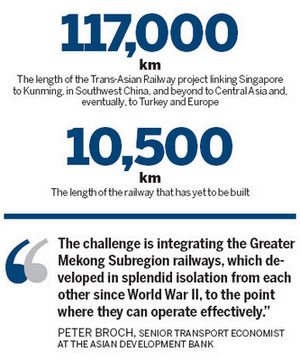

Cambodia's railways are among several missing links in the Trans-Asian Railway (TAR) project, an 117,000-km rail network, 10,500 km of which has yet to be built. Rehabilitating Cambodia's rail network is integral to the project that would link Singapore to Kunming, and beyond to Central Asia and, eventually, to Turkey and mainland Europe.

Envisioned in the 1960s, TAR would ultimately link the fragmented national railways in 28 countries into a unified transportation system.

"The completion of the missing links in the network and its efficient operations are key to the region's economic integration," according to Pierre Chartier. He is economic affairs officer in the transport division of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, which is driving the project.

The scope of this undertaking is massive. Some countries in the network have no railways to speak of; others have dilapidated ones.

|

|

Making connections

Chinese investment in domestic and foreign projects is driving forward the development of TAR, but more than money is required. Missing links between countries have to be filled and infrastructure built to overcome significant technical differences before a single, unified rail system can run smoothly across the continent. For instance, the width of tracks and, in turn, the axles of trains often vary from country to country.

"Financing and building railway infrastructure is easy. The challenge is integrating the Greater Mekong Subregion railways, which developed in splendid isolation from each other since World War II, to the point where they can operate effectively," said Peter Broch, senior transport economist at the Asian Development Bank.

"Effective cross-border rail traffic would provide medium- to long-distance land transport, thereby improving economic efficiency," Broch said. Transport and transaction costs would be reduced, and national economies could be better linked.

A 128-km link from the small city of Loc Ninh, along the Cambodian border, to Ho Chi Minh City will provide one of the missing links. It is part of a national plan Vietnam developed in 2002 to rehabilitate and turn Vietnam Railways into a corporation. Once that bit of the system is laid out and operational, it will be up to Cambodia to link it up with the wider transnational network.

Sizable economic zone

There are myriad options to overcoming technical hurdles such as varying rail gauges, the distance between rails, but all of these have problems of their own and would interrupt the smooth flow of traffic. The upshot is that despite tens of thousands of kilometers of track already laid, the original goal of a seamless network remains elusive.

There is, however, much merit in the idea of a continental rail network. For one, there are a dozen landlocked countries in Central Asia.

Southeast Asia, the area from southwest China to Singapore, could particularly benefit. An integrated railway would be another step toward "creating a large, reasonably homogenous market" similar in size to the European Union, Broch said.

The UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, forerunner of Chartier's agency, floated the idea of TAR in the 1960s to provide a 14,080-km rail link between Singapore and Istanbul. Over the following decades, countries moved forward railway projects and sometimes linked them, but coordination was limited.

Nevertheless, by 2001 TAR evolved to the point that four clear corridors had been developed and studied:

The Northern Corridor links Europe and the Pacific Ocean through Germany, Poland, Belarus, Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, China, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea.

The Southern Corridor goes from Turkey to Thailand through Iran, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Thailand, and includes links to China, Malaysia and Singapore.

The North-South Corridor would link Northern Europe to the Persian Gulf.

The Southeast Asian Corridor would link Kunming to Singapore.

In November 2006, 18 countries signed the Trans-Asian Railway Network Agreement, which covered some 81,000 km of railways. By the time the agreement took effect, in June 2009, a further 11 countries signed up and the network swelled to 117,000 km. Since then, 16 countries have officially ratified or accepted the deal.

"The development of the Trans-Asian Railway is not time-bound. It is evolutionary by nature and in this respect follows policy options of governments as well as the worldwide economic environment," the UN commission's Chartier said.