NGO workers find good deeds unrewarded by meager wages

Updated: 2011-11-15 07:25

By Shi Yingying (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

The work done by professionals for nonprofit groups, such as a non-governmental organization (NGO), is often undervalued.

|

|

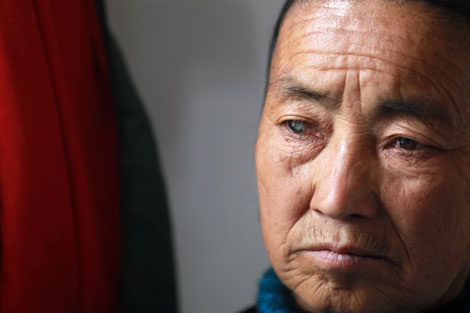

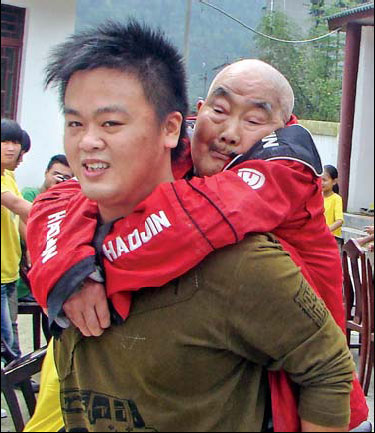

Volunteer Zhou Xuanci helps an elderly man following the 2008 earthquake in Anxian county, Sichuan province. [China Daily] |

And donors don't understand that providing charity does cost money. It isn't free.

So Xu Zhenjun opted to sleep late one Monday and idle away the rainy day. "I am on strike with my two colleagues," Xu, who runs an NGO in Kunming, Yunnan province, said.

Xu, and other NGO professionals, decided not to work on Nov 7. "We didn't go out onto the street with signs, shouting slogans. We simply chose to not show up at work on the first Monday of November," Xu said.

They also posted notices online about their intentions. Xu's aim was to deliver a clear and specific message in the hope of gaining public support. Salaries for nonprofit professionals need to be increased 10 to 20 percent, by the end of this year, he said.

"We (nonprofit professionals) were in short supply 10 years ago and will be 10 years from now because of the poor pay," he said. "A colleague of mine, earning just over 1,000 yuan a month, told me he couldn't afford pork because it was 40 yuan a kilogram in the market. That's pathetic."

A survey conducted in October 2010 by the Narada, Tencent and Liu Hongru Financial Education Foundations found that almost 90 percent of NGO employees earn less than 5,000 yuan ($787) a month.

More than 18 percent of the 5,000 NGOs that participated said their salaries were under 1,000 yuan or they didn't have fixed income. Most who were paid more than 5,000 yuan worked for foundations.

"The younger generation can usually survive for the first couple of years after their graduation," Xu said, "but soon after, they get to marriageable age and figure they've got families to support, and they quit."

Xu is 37 and said he is "all right" financially but is concerned about others who also love the kind of work they do.

Entry-level salaries at NGOs aren't much different from those at for-profit companies, he said, but businesses give pay raises "almost every year, and NGOs can barely do that".

"A few years pass and when you finally get up the nerve to ask for a better salary, you realize that your boss, who has been working in the field for more than 10 years, is earning 3,000 yuan a month - just a little bit more than you."

The survey also showed that only 28 percent of NGO executives have salaries over 5,000 yuan.

Dream vs reality

Friday was Jian Chuntian's last day at China-Dolls, the Beijing NGO that assists people with osteogenesis imperfecta, also called brittle-bone disease. It was also his last day in nonprofits since he started as a volunteer eight years ago.

Why drop out now? "I'm getting married," said Jian, who is 27.

His girlfriend is four years younger and a recent college graduate, so doesn't have much earning power now. Besides, he said, "My parents are old-fashioned and regard my job at an NGO as doing good deeds, but they can hardly understand it as a career. To quit this job is the hardest decision in my life.

"There's too much pressure. I need to buy an apartment in order to get married, and the wedding is costly as well. Many people have said I gave up my dream, but for me, the real dream is based on a foundation of reality."

Wang Yi'ou, the founder of China-Dolls, said, "Jian left without any request for a salary raise because he knew how much we could offer. We understood why he chose to leave."

Who will work

The wages that nonprofits are able to pay helps define their employees. Wang said that for organizations like hers, "We can't hire the best and brightest people when they can make more money in a for-profit business."

And women outnumber men, according to professionals at several grassroots NGOs. "For example, over 70 percent of my employees are female," said Liu Yonglong, secretary-general of Grassroots Community in Shanghai, whose services include free legal consulting. "That is probably because the man is born to support the family, under the traditional Chinese view."

Liu, 37, is an exception. He said he earned much more than his wife when he was an executive at a State-owned enterprise, "but now her salary is twice as much as mine."

He said his organization's average employee turnover has run as high as 100 percent in a year, mainly due to the poor pay. The seven full-time workers each take home about 2,000 yuan a month.

Liu's office shares its street address with a public toilet.

Mother's idea

As for Xu Zhengjun, the idea of calling for an NGO strike came from a phone call from his mother in May. "She asked about my financial situation as usual, because both of my parents worried about it since my wife and I have devoted ourselves to NGOs," he said.

"At the end of that call, she said why don't you organize something like a union to improve NGOs' issue of low pay? All these young men working at grassroots NGO, they have family responsibilities, they need to support their parents and they need to save money to get married despite the poor pay. Why don't you do something to help?"

The idea grew from there, Xu said. He and his two colleagues "posted four wishes - our four most urgent requests - all over the Internet . . . starting a month ago. My four wishes are that I want better salaries, I wish to raise my employees' pay, I want more people to join us and I wish more attention from society."

People don't know

The day before Xu's strike, a panel discussion in East China's Hangzhou about NGO salaries attracted representatives of 15 local NGOs in person and more than 25 online from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Sichuan and Yunnan.

The local organizer, Wei Jun from Dishui Public Welfare Association, said he'd rather that the group's conclusion be presented as the cost of charity rather than a call for better pay.

"The general public doesn't have any idea what charity costs," Wei said. "They think it costs nothing - no human resources nor any transportation and fuel expense is involved - to do good. That's why we don't get paid well or don't get paid at all."

A simple example, he said, is sponsoring a poor child in Guizhou at school for one semester, with tuition of 300 yuan. "But it costs me another 50 yuan to send an employee to a remote spot to do the investigation, to see who needs help most. That's 350 yuan in total. The donors, however, refuse to give the extra 50 yuan as they think we're trying to make money out of this."

Wei said he used to spend his personal savings to cover expenses, "but it's not a long-term strategy because there's too much overspending. I spent my savings like water in the year of the Sichuan earthquake."

10% or less

Amity Bakery in Nanjing hires mentally disabled people as employees, and its financial supporter, Amity Foundation, earmarks 10 percent of each donation for overhead, said general manager Zhu Guangquan. "It's very common in foreign countries, but some Chinese donors don't understand it and they question it."

Grassroots NGOs are not covered by China's regulation on foundations, but it provides a guideline. And the regulation says foundations can spend up to 10 percent of donations on expenses.

One billionaire from East China's Fujian province challenged the rule by pushing the bottom line. In May 2010, Cao Dewang donated 200 million yuan ($31.5 million) for five drought-affected provinces in Southwest China on one condition - that overhead be kept within 3 percent. Cao sent a team to monitor the money distribution.

One result was that China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, which administered the donation, paid for any expenses over 3 percent. The foundation has government support, so "it could afford such a loss, but we can't," Wei said. "So it is with China's grassroots NGOs."