Murder most foul

Updated: 2011-09-16 07:48

By Chitralekha Basu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

The body of Pamela Werner, whose gruesome murder is illustrated in Paul French's new book, was found at the base of Dongbianmen watchtower. [Feng Yongbin / China Daily] |

The death of a young English woman in 1930s Beijing has a new book and ending. Chitralekha Basu reports.

Paul French stands on the edge of a thin white bridge over what used to be a grand canal in early 20th century Beijing (then Peking), bringing merchandize into the city from Chinese shores. The massive Dongbianmen watchtower, one of the last vestiges of imperial vigilance at the southeast corner of the remains of the city wall, forms the backdrop.

"This is where Pamela Werner's body was found," French says, pointing to the tower's base, referring to the story of the gruesome murder of an English girl in Peking, in January 1937.

"Also known as the Fox Tower, as it was believed to have been haunted by fox spirits, the tower was home to thousands of bats and the feral huang gou (yellow dogs). You didn't want to be here at night."

For one who has visited this spot often over the past seven years, French seems as emotionally invested in Werner's story, as he was the day he chanced upon it for the first time. French, a Shanghai-based historian and analyst of Chinese culture and society, found the thread in a footnote in the biography of American journalist Edgar Snow (of Red Star Over China fame).

Snow was Pamela's neighbor in Peking's Armor Factory Alley. Reports containing macabre details about Warner's severely mutilated body sent shockwaves through the expat population who became seriously worried about their safety.

|

French followed up the story of the sensational murder of the teenage girl, the adopted daughter of a former diplomat and Sinologist, E.T.C. Werner, which had made headlines in The Times and the Chinese press, and wrote a piece in Beijing: Portrait of a City (2008), an anthology edited by Alex Pearson, owner of the Beijing-based Bookworm store.

"When I wrote that story I had no idea who the murderer was," French recalls. After Penguin China commissioned him to work the idea into a book, French undertook an elaborate project to unearth every possible document related to the unsolved case.

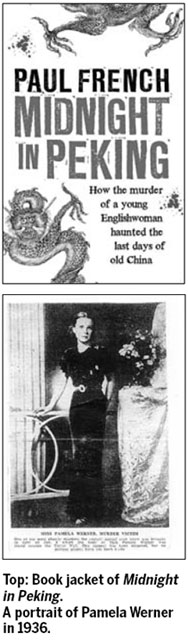

Once he had seen Pamela's photos, one as part of her Tianjin Grammar School group and the other, a studio photo of a teenage girl trying to pass herself off as a lady, writing her story became a moral obligation. "She became human to me," French says, referring to the aura of power a 19-year-old woman can command and how that very sexuality can make her vulnerable.

"I was overcome with the feeling that Pamela could still have been alive, telling stories to her grandchildren. I feel the equilibrium of the world gets shaken up when some one gets cut off in the prime of her life."

He located people who knew Pamela and responded to his online hunt about more information. "They are now in their 80s and 90s, and some quite tech-savvy. They can speak freely now about a sex scandal that happened in the 1930s," French says.

Writing Midnight in Peking (launched in China this month and sold in 15 languages across the world, including Chinese) was a way of restoring poetic justice for Pamela. It was French's way of giving her "some sort of a life" beyond her horribly undignified death.

Midnight in Peking is also the story of a lone man's lifelong project to find the murderer of his daughter in a fast-changing, politically-volatile and somewhat-indifferent Peking - spanning the years of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945), the civil war (1945-1949), the internment of foreign nationals in Japanese military camps and ultimately the founding of the People's Republic of China and the onset of Communist rule.

E.T.C. Werner, who starts off as an unsympathetic, unfriendly character, and is, for a while, suspected of having a hand in Pamela's murder, turns out to be the story's unsung hero, whose only purpose in life was to catch his daughter's killer.

In fact, French located the vital clue to this real-life whodunit in "a box of jumbled up and unnumbered documents in the British embassy in China in the 1940s" in which there was a "150-page or so long document sent to the foreign office, by Werner".

It was his "Eureka moment". He felt like traveling across time and telling the detective chief Richard Dennis who relentlessly pursued Pamela's case against a sea of odds, including pressure from the British embassy asking him to look the other way, and telling him, "You were so close."

"Both Dennis and Colonel Han (his Chinese counterpart) were good cops and investigators but they were interfered with. I can sense how frustrating it must have been for Dennis," French says. "A detective makes a promise to the victim, which he was never able to keep."

The book is also attracting attention for its focus on old Peking. A massive campaign launched by Penguin China (see sidebar) is designed to inspire more readers to relive the charms of 1930s Peking, which for some reason has had limited visibility, when compared to the proliferation of images from old Shanghai in literature and kitsch art.

This is especially interesting, since French, who is British, has been a Shanghai resident for the last 17 years.

Beijing, French says, "is a different story" altogether, when compared to hot and happening Shanghai, which in the 1930s was a "foreign-administered treaty port and both the international settlement and French town were wide-open places where refugees did not need papers and gangsters ran amok".

"In Beijing you get much older stuff. Here people don't think of their narratives as belonging to the 1930s, even the locals forget that," he says. Recreating a forgotten era that readers do not associate with obvious images in their heads and making it believable was an added challenge.

Luckily for him, at a time when substantial parts of old Peking is being dismantled and built anew, Pamela's story is set in relatively newer parts of the old town. While the erstwhile Legation quarters are now walled compounds housing government offices, ("you can't go inside and if you're trying to take photographs the guards can get a bit jumpy"), Chuanpan and Huogou hutong, where Pamela was seen last before her death, are more or less preserved and accessible.

They do not look anything like the mesh of bars, brothels, drug dens and gangsters' haunts that they did on that fateful night when Pamela walked into one of the buildings, though.

"I used old pictures, newsreels, autopsy reports from Peking Medical College, archives of the British Museum, Library of Congress and the University of Hong Kong to recreate the scene," French says.

Having dedicated seven years to reconstruct the story of a young girl's brutal killing, French is not completely done with the story just yet. Even as he steps out to do book tours across the world, he is preparing a special edition of the book to be translated in Chinese.

Some of the historical bits in the English version, he feels, are over-familiar to the Chinese.

"For the Chinese version I'm putting in the other history, things like why were the Russians and Jews here in the early 20th century? Some of the descriptive things, detailing and so on, are going to be different in the Chinese version."