When the tough get going

Updated: 2011-10-25 08:01

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Former vice-minister of commerce Wei Jianguo, who spent 37 years in Africa, says he spent the best years of his life on the continent. [Zhang Wei / China Daily] |

Former vice-minister of commerce Wei Jianguo sums up his seminal contributions to expanding Sino-African trade in his just released memoir. Mei Jia reports.

Former vice-minister of commerce Wei Jianguo, 64, recalls with pride the time in 1992, when he stood up and spoke openly to China' "Iron Lady", former vice-premier Wu Yi, about the obstacles in Sino-African trade and their solutions. It is from that year that the total trade volume between the two sides began to grow - from less than $1 billion to $126.9 billion in 2010.

Wei, who had just returned from Gabon, where he served as commercial counselor for four years, was at the first meeting that Wu hosted as the new minister of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation (Ministry of Commerce since 2003).

He remembers the jitters he had before giving his speech, which turned out to impress Wu.

"My words caught Wu's attention because I understand Africa, and China's long-term friendship with African countries," Wei says, with the same frankness that he shows in his writing.

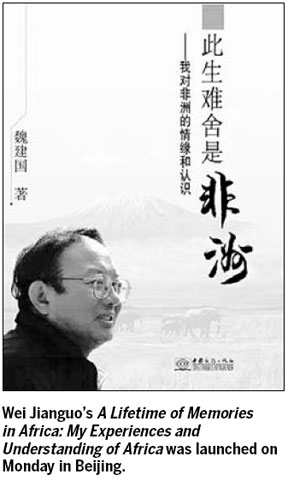

Currently serving on the country's prestigious think tank, the China Center for International Economic Exchanges, Wei offers an in-depth look at his nearly four decades of work in facilitating trade with Africa in his memoir, A Lifetime of Memories in Africa: My Experiences and Understanding of Africa, which was launched in Beijing on Monday.

|

Hu Kaimin, associate editor-in-chief of the Foreign Languages Press, who is working on the English and French versions of the book with Bertelsmann, says his team expects to present the book to international readers in early 2012.

"Wei has told a wonderful story of personal growth - from being a language student to a high-level official," Hu says.

"Meanwhile, the book details the history of Sino-Africa relations and of the formation of China's trade policies that Wei witnessed and experienced," he adds.

Wei says, "All my life I've been doing one single thing: working with African countries and its people.

"My connections with Africa have changed my life and shaped me."

Born to a family of modest means in Jiangsu province in the 1940s, Wei's early dream was to become a military engineer.

He says the events of his childhood, the struggling country and its effort to be stronger, struck him deeply.

While he was working hard to enter a military college, he received an unexpected chance to become one of only four students in the province allowed to skip the college entrance exams and go to university to learn foreign languages as diplomat candidates (so-called for being guaranteed a job in the ministry right after graduation).

He recalls being more shocked than happy.

Giving up his childhood dream was only the first of many tough decisions that Wei, faced with the twists and turns of life, has made over the years.

"When I look back, I see that when fate closed one door, it opened another for me," Wei says. "My choices were guided by this simple rule: to stay faithful to the ones who helped me, to my country and to my heart."

It is this same belief that helped him survive the labors in rural Anhui province during the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), and the hardships of living in Africa for 20 years.

One of the people Wei impressed on a plane back from a visit to African countries in 2008 was Li Changchun, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Party's Central Committee.

"Li suggested I write a book to sum it (his life story) up, which he said would make an interesting and inspiring read," Wei says, adding that he took the next two years to complete the book.

Li commends Wei's efforts in the preface, calling the book a vivid history, a travel guide and a growing-up story.

"Wei's story tells that only when personal pursuits are in line with the country's bigger picture, will people find and realize their value," Li writes, adding the book is a good role model for younger readers.

He Song, a young official from the West Asian and African Affairs Department of the Ministry of Commerce, says he felt inspired after reading Wei's book.

After working at Chinese embassies in Morocco, Tunis and Gabon for two decades, Wei returned as head of the department in the ministry that deals with African countries.

A defining quality of his life is his persistence. While in Morocco, Wei saw two ships arriving - one with Chinese tea and the other with Japanese cars. He was shocked to find that the value of a whole shipment of Chinese goods equaled just one car from Japan. He decided it was time to expand Sino-African trade.

He began by establishing China's own banking organizations in Africa and opening lines for ocean transportation. He went back and forth between the relevant organizations innumerable times to persuade them.

Eventually, he opened up a new path.

Wei readily admits to his tenacity and credits his strong will power to his daily jogs - a habit that has stayed with him since his school days.

"I've been to 218 countries, and have always lugged my jogging gear," he says, "Excuses for a rest are many as I travel a lot, but I tell myself the moment I step out and close the door behind me, I can win, (yet) again."

The think-tank member believes that China and African countries should have tighter cooperation, "for the world is better off once both sides make progress".

"I believe, counting on Africa's huge progress recently, the trade volume between the two sides will reach $300 billion in three to five years," Wei says, "which means Africa will become part of the team A of China's trading partners."