Prosing the question

Updated: 2011-12-15 07:57

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

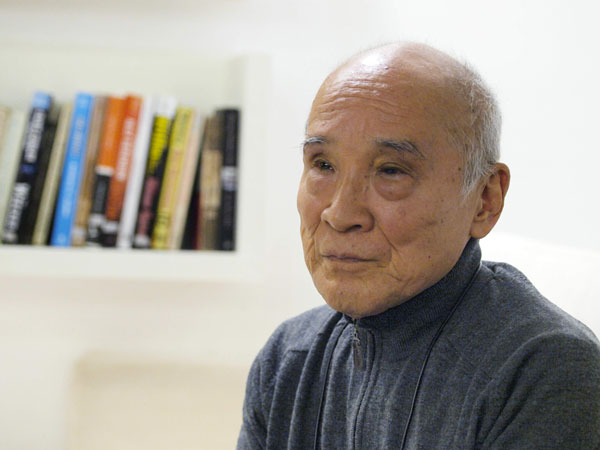

Tanikawa Shuntaro's work appeals to a wide range of readers, including housewives and professionals. He believes poems are not only for "narcissistic self-satisfaction". Qi Shangmin / For China Daily |

A Japanese poet, who says he'll turn down the Nobel he's likely to win, wonders about humankind's place in the universe. Mei Jia reports.

Japanese poet Tanikawa Shuntaro has been high on the list as a Nobel Prize in Literature candidate. But he says he'd forgo the honor if it's awarded to him. "I reject the political inclination of the prize and any others of the kind," Tanikawa says.

"Readers are my Nobel."

The poet displays similar disdain for honorifics and opportunities he regards as undeserved. He turned down writing requests after March's massive earthquake in his homeland, because he insists he can't write as if he were a victim of the disaster because he isn't. He donated money instead.

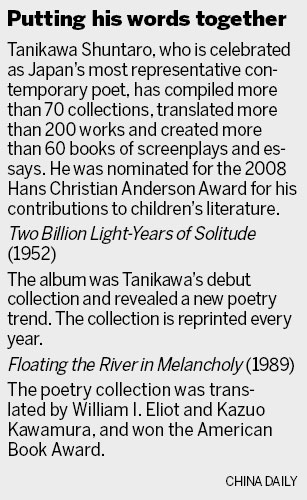

But the 80-year-old did accept the Third Zhongkun International Poetry Prize in Beijing on Dec 6, along with 89-year-old Chinese poet Niu Han.

Organized by the Peking University Institute of Poetry Studies and sponsored by Zhongkun Poetry Development Foundation, the prize is a bi-annual non-governmental honor celebrating the winners' lifetimes of creative work. Previous champions include Zhai Yongming, Bei Dao and Syrian poet Adonis.

Tanikawa won for "changing the readers' perception of Japanese contemporary poetry and enlightening Chinese poetic creation", the panel of judges said.

"Contemporary Chinese poems tend to be abstract and hard-toned," judge Tian Yuan, who is also a Chinese literature professor at a Japanese university, says.

"But Tanikawa brought a plain, lively and interesting style. I know Bei Dao began to write rhymes for children after Tanikawa."

Indeed, the "short, bald, old man" as Tanikawa calls himself, is widely read in his homeland, and Chinese and English translations of his works are popular abroad. One of his English-language collections won the American Book Award.

He's also known for infusing Japanese poetic traditions with Western elements, and for constantly experimenting with form, style and media.

Tanikawa wrote the lyrics of the theme song of Miyazaki Hayao's popular animated movie Howl's Moving Castle. He has written anthems for more than 100 Japanese schools, which he describes as challenging because they're specific to the schools' unique environments, histories and features.

In terms of media, he has written poems on Apple applications, under microscopes and on T-shirts.

He lives better than his Chinese contemporaries, earning annual royalties of $800,000 in lean years.

His Chinese translator, Tian Yuan, jokes that Tanikawa is probably the world's wealthiest writer in terms of copyright earnings.

|

"But I've been writing for more than 60 years to achieve this," Tanikawa says.

Tanikawa was the only child of a philosopher father and a Christian mother. He grew up with an English-speaking tutor, which enabled him to translate numerous children's tales and poems in later life.

His childhood aspiration was to grow up to assemble radios.

Tanikawa began penning prose at age 17, at a friend's suggestion. Those initial works were published, launching his lifelong career.

"I never thought about quitting because I have to support myself and my family through writing," he says.

Tanikawa tried every kind of writing and developed a sense of reader-oriented creation, he says.

"Poems are not only for narcissistic self-satisfaction," the poet says.

"I write to see if my works will be of some help to others."

Tian believes Tanikawa's charm comes from his poems' appeal to different readers, including housewives and professionals.

Tian quotes an anecdote from Nobel-winning writer Ooe Kenzaburo's personal account, which says Ooe's dream of being a poet gave way to that of becoming a novelist after reading Tanikawa's works.

Tanikawa says he has only found writing poetry to be fun in the past 10 years. He has been an outsider in Japanese poetry circles and has enjoyed the distance from his peers, he says.

He believes poetry should be read by broader audiences rather than created and consumed within small circles.

"I'm seeking the voice many others will easily sympathize with," he says.

He's also working to find a voice that won't lose color when translated.

"I understand the contemporary poetry in my country shares the same problems with China's," he says.

"(It's) struggling in between the greater influences of ancient poetic traditions and of new Western-style works introduced later. They both lack readers, creativity and true feelings. Poems without feelings and content instantly fade after translation. Writers might be the ones to blame."

Zhongkun prize judge and Chinese Academy of Social Sciences poet and translator Chen Shucai believes contemporary Chinese poetry mirrors social illnesses.

"Through awarding Tanikawa, who has found his own poetic voice in a changing world, we hope to give Chinese poets and readers a role model to reexamine poetry's social functions," Chen says.

|

Japanese poet Tanikawa Shuntaro (left), 80, and Chinese poet Niu Han, 89, accept the Third Zhongkun International Poetry Prize, in Beijing, on Dec 6. Mei Jia / China Daily |

Tanikawa believes his age is something that plays into his understanding of life in flux. He compares ages to tree rings.

"No matter how old I grow, the younger me still exists in the center ring," he says.

"I evolve around my childhood and let the younger me go freely without suppression."

The young Tanikawa was well protected by his mother and never endured the fighting that often takes place among brothers.

"So my focus is always on my relationship with the universe - not on social relationships," he says.

The exploration of a human being's place in the universe is a common thread among his works.

"I don't fear death, because I've been writing," he says.

"I leave no regrets in this regard."